'The Truman Show' At 20: Jim Carrey's Best Movie Is Still Delightful And Philosophically Rich

In 1994, Jim Carrey broke big, starring in Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, The Mask, and Dumb and Dumber, three box office toppers that catapulted the rubbery-faced comedian to global superstardom. There's an entire generation of kids that went around quoting those movies, repeating Ace's catchphrase of "Alrighty then!" while affecting the same overly confident voice that Carrey had first workshopped as a different character in sketches on the TV show In Living Color.

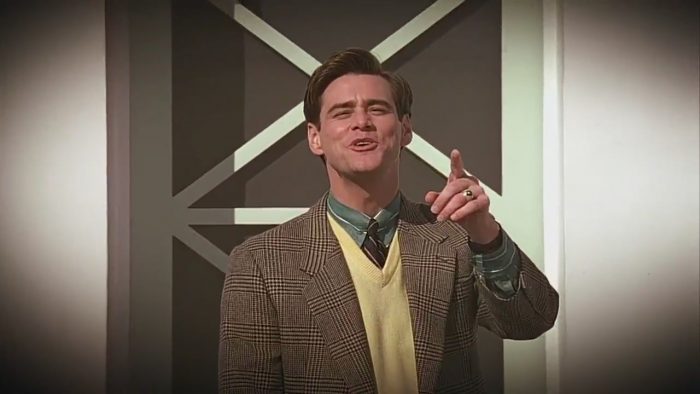

One thing Carrey wasn't was a critical darling. It may have taken his Batman Forever co-star, Tommy Lee Jones, to come right out and say it, but it was implied often enough in reviews that not everyone could "sanction" Carrey's "buffoonery." This would change somewhat in 1998 when the actor reinvented his slapstick schtick with a film that Popular Mechanics later ranked as one of the 10 most prophetic sci-fi movies ever. Released on June 5, 1998, The Truman Show famously presaged the reality TV boom and saw Carrey passing through the door to more seriocomic fare like Man on the Moon and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

20 years later, The Truman Show remains Carrey's best film. But what makes this movie timeless is the level on which it functions as a beautiful, satirical allegory.

In The Truman Show, Carrey linked up with Peter Weir, a director with a more dramatic pedigree who had nonetheless brought out the best in another comedic actor — the late Robin Williams — in Dead Poets Society. The film's screenwriter, Andrew Niccol, had also written and directed the science fiction film Gattaca the year before. With Carrey's comedic background, all the elements were in place for a unique sci-fi comedy-drama that would herald the rise of reality television. A few years later, you wouldn't be seeing music videos on MTV anymore; you'd be seeing reality shows.

Carrey plays Truman Burbank, a man born and raised in a giant dome without the knowledge that his entire life serves as a carefully controlled show, one broadcast around the world 24/7. Truman's first name invokes the idea of a "true man," while his last name brings to mind Burbank, California, the media capital of the world.

Each and every day, Truman goes about his cheery business, saying hello to his neighbors, listening to the radio on his morning drive to work, visiting the same newsstand ... all the while oblivious to the fact that the population of Seahaven Island, where he lives, is made up entirely of actors. Even his wife and best friend are on the payroll.

Since "The Truman Show" is live, the actors often receive their lines in an earpiece from Christof, the show's creator, played by Ed Harris. Harris has since gone on to star in HBO's Westworld, a show where theme park robots are made to live in a loop until they begin questioning the nature of their reality, much like Truman.

What keeps Truman in check at first is fear. To dissuade him from ever venturing outside the finite radius where lives, Christof gave Truman a key piece of childhood trauma, killing off his TV dad in a boat accident. Now Truman has a fear of water, yet he lives on an island, so that means he's hemmed in constantly by what he fears most. Even when he gets up the gumption to visit a travel agent and live his dream of traveling to Fiji, he is bombarded with anti-motivational messages, like a poster that juxtaposes an airplane struck by lightning with the not-so-subtle communique, "It could happen to you!"

What keeps Truman in check at first is fear. To dissuade him from ever venturing outside the finite radius where lives, Christof gave Truman a key piece of childhood trauma, killing off his TV dad in a boat accident. Now Truman has a fear of water, yet he lives on an island, so that means he's hemmed in constantly by what he fears most. Even when he gets up the gumption to visit a travel agent and live his dream of traveling to Fiji, he is bombarded with anti-motivational messages, like a poster that juxtaposes an airplane struck by lightning with the not-so-subtle communique, "It could happen to you!"

There are, however, glitches in Truman's matrix. Spotlights fall from the sky, improbable rain clouds follow him around like a cartoon character, and actors do occasionally break character on set, such as Sylvia, his long lost love from college. Sylvia was never intended to be anything more than an extra on the show, but Truman spotted her and took a liking to her, even as a character named Meryl was being groomed as his future wife.

Eventually (and major spoilers from here on out), Truman starts living up to his name. Awakening to the falseness of his reality, the "true man" realizes he's trapped in a bubble and then decides to go gloriously off-script, testing the boundaries imposed on him and doing everything within his power to break free of life's limitations. It all comes to a head in the scene where Truman raises his hand to stop traffic, his sudden godhood powered by a piece of Phillip Glass music, appropriately titled "Anthem." No, he's not just paranoid: there really are unseen forces manipulating his moves.

Truman's allegorical journey is a little different from the one in Paulo Coelho's bestseller The Alchemist, where "When you want something, all the universe conspires in helping you achieve it." In Truman's case, the universe actually seems to be conspiring against him, doing everything within its power to keep its binding mechanisms in place over his life. Yes, he is being watched (and rooted for) by an audience full of eyes outside the world he perceives. But those viewers, like the security guards we see munching pizza before the closing credits roll, are more passively observing, liable to change the channel if and when Truman ceases to entertain them.

It's inspiring in the weirdest and loneliest of ways because it puts the onus on Truman to have his own agency. No one is going to help him; everyone is just watching to see if he'll help himself. He's got to be the author of his own fate.

The Truman Show is a film that has given rise to a multitude of interpretations. In a feature last year about David Fincher's The Game, I wrote about the Millennium Bug: not the one in computers, but the one in movies. The Truman Show is one of those paranoia-laced Millennium Bug films. Its Matrix-esque narrative has even made it fodder for conspiracy theories. There's a whole disorder called "The Truman Show delusion" or "Truman syndrome" where people believe they really are the star of their own reality shows, being watched by hidden cameras.

When Christof puts himself on the loudspeaker in a last-ditch attempt to prevent Truman from leaving the dome, it's as if the voice of God is now addressing Truman. People point to Christof's name as another obvious indicator: either he's meant to be a critique of religion as a restrictive paradigm, or he's meant to be an off-Christ, the megalomaniacal devil-producer, exercising dominion over the earth from his lunar-lit control room, keeping Truman confined to his simple, slave-like routine. When Truman ascends that cloud-camouflaged staircase and steps through a door into the unknown — finally freeing himself from Christof's grasp — it does make it seem like he is ascending into heaven.

The Truman Show could also just be seen as a story about a kid outgrowing his playpen—in which case Christof becomes the overprotective father who wants to shelter Truman from the real world. There's clearly a layer to the movie that seems designed to make us think about how the media shapes our perceptions, as well. As Christof puts it, "We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented."

In a year when the trusted image of public figures seems more precarious than ever, that's certainly something to think about, especially for those of us who hold cinema itself and its purveyors in an almost religious regard. The recent Netflix documentary Jim & Andy: The Great Beyond showed how even the Carrey we saw back in the late '90s was a studio-managed media figure, one who secretly became a method-acting terror on the set of Man on the Moon, channeling Andy Kaufman to the degree that Universal Pictures suppressed behind-the-scenes footage of the film "so that people wouldn't think [Carrey] was an asshole."

The end of that documentary utilized imagery from The Truman Show as Carrey stared unblinkingly at the camera and talked about what the movie meant to him. Not surprisingly for an actor, he related it to his own identity crisis as a creative person, saying it forced him to examine how the life we're born into imposes abstract societal structures on us and we come to be defined by the labels our parents give us.

"At some point, you have to live your Tru-Man. I mean, Truman Show really became a prophecy for me. It is constantly reaffirming itself as a teaching almost, as a real representation of what I've gone through in my career and what everybody goes through when they create themselves."

Whatever you think about Carrey, it's clear The Truman Show exerts a powerful hold even on his imagination. "You step through the door not knowing what's on the other side," he says at the documentary's end, "and what's on the other side is everything."

Not every movie needs to be "a teaching" that imparts some profound life lesson, of course, but The Truman Show is a film that openly invites discussion and debate in a disarming, delightful manner. That such a wealth of weighty ideas can be extracted from a PG-rated film is a testament to Truman and his sublime innocence. Two decades after its release, his story remains fresh in how it illuminates aspects of the human condition: bringing notions of selfhood and reality into the light like a bright beam peeking over a premature horizon, called forth by a man in a control room with the words, "Cue the sun."