Netflix's 'The King' Spoiler Review: Shakespeare Without The Dialogue, Anchored By An Intense Timothée Chalamet

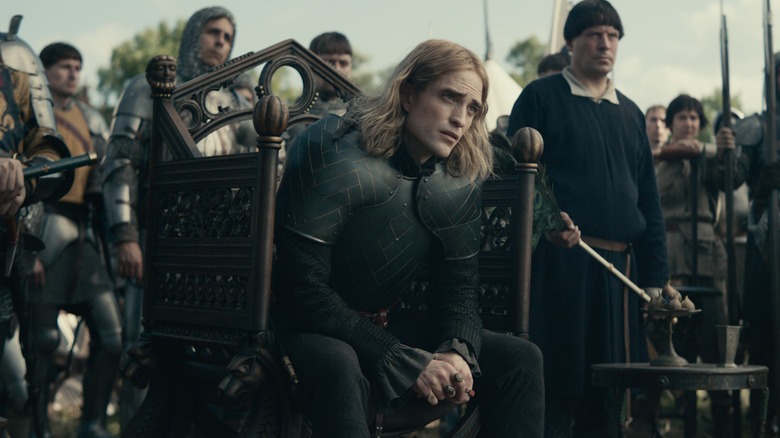

Netflix's The King is a reverse Hobbit: instead of adapting one book into three movies, it adapts three plays into one film. Shorn of Shakespearean dialogue, this loose retelling of Henry IV, Parts 1 & 2 and Henry V gets by on character and plot. Timothée Chalamet brings a brooding intensity to the Henry V role, which sees him following in the footsteps of classically trained luminaries like Sir Laurence Olivier and Sir Kenneth Branagh. That he can hold his own as a screen presence, even in comparison to thespians such as those, bodes well for his starring role in next year's Dune.

The King also reunites director David Michôd with Joel Edgerton and Ben Mendolsohn, two actors who broke out internationally after appearing in Michôd's 2010 Australian crime drama, Animal Kingdom. Edgerton serves as Michôd's co-writer here, just as he did for the 2014 dystopian outback Western, The Rover, starring Guy Pearce. Michôd brings back Robert Pattinson from that movie; like Chalamet, Pattinson is no stranger to heartthrob status, and he's set to headline a future tentpole (just a little movie called The Batman).The King arrives in a post-Game of Thrones landscape where at-home audiences have become inured to watching court intrigue play out in medieval settings. Yet its source material predates Game of Thrones by centuries. Writer George R.R. Martin drew from the same period of history as Shakespeare's Henriad, the cycle of plays that this movie partially adapts. Among other things, The King depicts the muddy hell of the Battle of Agincourt, the original inspiration for the Battle of the Bastards. This may not be Westeros, but war is still bloody and mud underfoot is an apt symbol for the innocence-to-experience arc that Chalamet's conflicted prince undergoes as he dons his father's crown and enters the moral quagmire of adulthood.

The Players Well Bestowed

While not perfect, The King is a film that benefits greatly from its performances. Mendelsohn's screen time is limited but he comes across as such a capricious Henry IV that when one of his captains, Hotspur, insults him openly at the table, you're never sure if he's going to order the man's death right then and there. Edgerton also makes an immediate impression in his first scene as Falstaff—a friend to Chalamet's character, Prince Hal, who is the king's estranged son. Hal starts out the movie sleeping in late and engaging in drunken revelry at night. By the end, he'll have a lot of French blood on his hands.

Bearded and beefier thanks to burrito consumption, Edgerton looks like he's having more fun onscreen than he's had in a while. At the very least, he hasn't been such a lively presence, character-wise, since his role as Tom Buchanan in The Great Gatsby. Falstaff is a fictional character, invented by the Bard, which is what keeps The King tethered to the realm of entry-level Shakespeare (e.g. the Mel Gibson Hamlet), as opposed to it just being a different dramatization of real historical events.

Also on hand is Dean-Charles Chapman, the actor who played Tommen on Game of Thrones. Here again, he's cast as the weak, ineffectual younger brother in a royal family: Thomas instead of Tommen. Hal is able to easily assert himself over Thomas when he makes an unscheduled visit to the battlefield where Hotspur is leading a rebellion against the king. He challenges Hotspur to a one-on-one duel, for the fate of both armies, and their sword fight quickly turns into a knock-down, drag-out fist fight in full medieval armor.

Eschewing Shakespearean dialogue does lead to some awkward little anachronisms in The King, such as when Thomas whines, "Still, you find it necessary to upstage me," and Hal responds, "I do this not to steal your thunder, brother." The Bard introduced so many words and phrases into the English language that it's easy to lose sight of the origin of some of them, but while "upstage" is theatrical jargon, its etymology only dates back to 1855—hundreds of years after this film's time setting. "Steal one's thunder" is a little older but still shy of Shakespeare or Henry V's era. It does bear an incidental connection to Shakespeare, however: the phrase originated when a failed playwright who had devised a new sound effect method for thunder caught a theater that rejected him using his method during a performance of Macbeth.

These are just nitpicks, really. If The King suffers from an occasional imprecision of language, it's a minor qualm. Shakespeare himself penned any number of lines that might sound funny out-of-context in the 21st century. Henry V, for instance, contains the line, "Tennis balls, my liege," and while it might have made for a great meme, it's probably better that we don't have to see Chalamet reacting to that line with a solemn face.

Other reviews have commented on the coming-of-age aspects of The King; these come into focus when Thomas and Henry IV both die and Hal inherits the crown, along with the byname Henry V. Surrounded by lisping archbishops and obsequious advisers, Hal is immediately thrust into situations that test his humanity and inner strength. When one of his former friends betrays the crown, he has to steel himself while he watches that friend and another man beheaded. "Kings have no friends, only followers and foes," Falstaff tells him.

Spurred on by an insulting gift and an assassination attempt (which we'll later find out was staged), Hal finally relents to pressure from his advisers and declares war on France. When he enlists Falstaff's counsel, he praises him for his "grim sobriety." The King itself has an air of grim sobriety, which is helped by Nicholas Britell's portentous score.

Coming into this film, I was relatively new to the Chalamet phenomenon. As it happens, Call Me By Your Name and Lady Bird are the only two Best Picture nominees for 2017 that I haven't crossed off my ever-evolving to-view list of movies. I mainly knew Chalamet from supporting roles in films like Interstellar and Hostiles.

Chalk it up, if necessary, to this being my first real exposure to him as a star, but I bought into his performance wholeheartedly and thought it went a long way toward carrying the movie. Rousing pre-battle speeches peaked with Braveheart, and are generally my least favorite part of these kinds of movies, but when Hal gets down from his horse, vociferating to his men with the vein on his neck bulging, the level of raw emotion on display reminded me of the young Leonardo DiCaprio in William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet.

The only thing that didn't track for me was how quickly Hal seems to change in The King. He's a holdout for peace, but it doesn't take long for him to turn imperious, getting in Falstaff's face and saying, "How dare you defy me? I will disembowel you here with mine own hand." This can maybe be seen as false bravado that he affects in order to project strength, or it can be seen as something in his blood, the legacy of his mercurial father.

Either way, this is where having Henry V played by a younger actor works in the movie's favor. It's easier to swallow Hal being volatile and easier to swallow him being deceived by his shifty Chief Justice, Gascoigne (Sean Harris), when he's barely older than a college grad and he has the weight of all this responsibility for England pressing in on him.

For his part, Pattinson is ten years older than Chalamet and he's spent the last several years working with serious-minded directors like David Cronenberg, James Gray, and Robert Eggers. Fresh off his Maine accent in the artsy — and literally fartsy — The Lighthouse, the future Batman sports a loopy French accent in The King. The Dauphin allows him to sink his teeth (Twilight pun intended) into a rare, scene-stealing, villainous role, and the movie is better off for it.

A War Predicated on a Lie

Shakespeare's plays can be so diffuse in terms of characters and subplots that they almost beg to be streamlined by modern filmmakers sometimes. The King comes thirty years after the aforementioned Sir Kenneth Branagh made his directorial debut with a much more faithful adaptation of Henry V. Branagh's 1989 version is one of those rare films that holds a 100% on Rotten Tomatoes. If you go back and watch it now, there's a breathless bombast to that movie and it ends with a kind of giddy sitcom cheer—which almost undermines the gritty realism of its Battle of Agincourt. It's easy to see where those qualities would carry over into later films of his like Mary Shelley's Frankenstein and Marvel's Thor.

Branagh's Henry V is a hale and hearty fellow who strides right into war based on a single slight from a foreign ruler. (That actually sounds like something that could very plausibly happen in 2019, but I digress). After the dust has settled on the Battle of Agincourt, he reads a list of the war dead and realizes that he's killed ten thousand French soldiers at the expense of twenty-five of his own. Praising God and throwing the dead body of a young Christian Bale over his shoulder, he leads a procession off the battlefield, accompanied by a soaring Latin hymn. The movie ends by following Shakespeare's play, which shifts tones from a history to a comedy in Act V.

The King has no place for such comedy or any sort of grandstanding. While it may come across as dour to some, the movie gives more serious consideration to the corrosive effects of power and the real implications of warmongering. Hal emerges victorious, yet he's fought and won a war that was predicated on a lie. When he finally sits down face-to-face with the King of France, the older monarch surprises him by making an unconditional surrender and even cheerfully suggesting that Hal marry his daughter, Catherine (Lily-Rose Depp).

It's through Catherine that Hal realizes the abject folly of the war he's waged. Blood has been shed needlessly — including that of his friend, Falstaff, whose un-helmeted corpse he finds on the battlefield — all because Hal followed the self-serving advice of his Chief Justice. "Do you feel a sense of achievement? In any regard?" Catherine asks him. Hal talks about how he has united his kingdom in common cause, but she points out that it's "a momentary respite" and "a unity forged under false pretense."

Catherine brings a much-needed female perspective to Hal's insular sphere, breaking up the dichotomy of foes and followers with a potential peer. She's someone who can come right out and tell him: "I will not submit to you. You must earn my respect." Talking to him on this level, she gets him to realize that he can offer no good explanation for bringing war to France. "All I see is a young and vain and foolish man so easily riled, so easily beguiled," she says.

Resolving the story this way, by giving the protagonist a hollow triumph, is an approach that put me in mind of other revisionist literary adaptations like the 2007 mo-cap Beowulf and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (the latter of which was produced by Brad Pitt's Plan B Entertainment, just as The King is.) The notion of a short-lived peace, built on the foundation of a lie, is also one that played out in the graphic novel Watchmen, which is currently undergoing revived interest thanks to the HBO series of the same name. These may seem like tenuous comparisons, but they all share a common thread of ringing truer to human nature and the complexities of life than a straightforward, hail-the-conquering-hero type narrative would.

Chalamet's Henry V is one who is less satisfied with himself and less certain of his cause than Branagh's was. After confronting Gascoigne and stabbing him in the head, even as he kneels fulsomely before the king, Hal returns to Catherine, saying that he asks nothing of her save that she always speak to him "clear and true."

This is where he truly comes of age. He started out his reign determined to hold onto his humanity and not be like his father, only to push forward with a misguided show of strength and see his kingdom succumb to the same petty strife with a neighboring country. By the end, he's learned some hard lessons about the perils of navigating the adult world, while the movie has offered a sober view of the dubiousness of war: whether it be conflict with other countries or our own personal conflicts, the wars we wage daily on other people over little things. Maybe if the king had a sensible woman to call him out on his bullshit sooner, he wouldn't have let the older kids egg him on into invading a sovereign nation.

I was pleasantly surprised by The King. It may not be for everyone but you could do a whole lot worse than this with your Netflix night.