How Did This Get Made: The Apple (An Oral History)

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In 1977, an Israeli rock star and his musically talented wife decided to collaborate, for the first time, and write a musical for the stage: The Apple. But before the show was ever performed, a notoriously eccentric filmmaker persuaded them that their masterpiece should instead debut on the big screen with him as director.

A little over one year later, when The Apple premiered at the Montreal Film Festival, the Israeli couple was noticeably absent, and the eccentric director came within seconds of committing suicide. This is the sad, strange story of how that came to pass.

The Apple Oral History

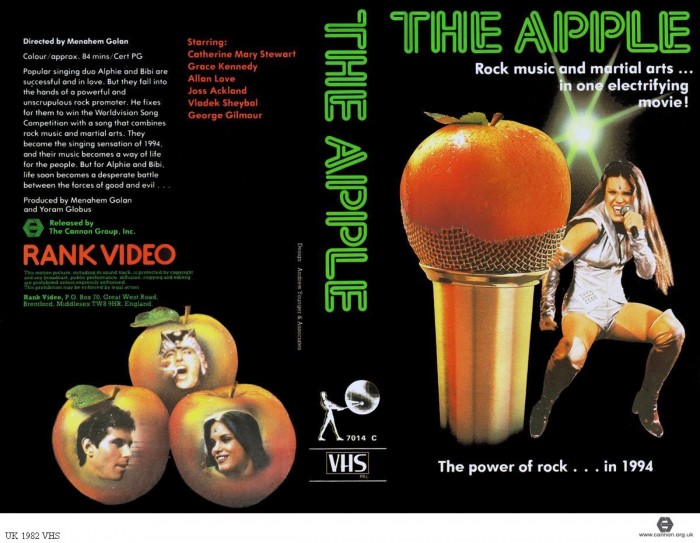

How Did This Get Made is a companion to the podcast How Did This Get Made with Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael which focuses on movies. This regular feature is written by Blake J. Harris, who you might know as the writer of the book Console Wars, soon to be a motion picture produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg. You can listen to the The Apple edition of the HDTGM podcast here.  Synopsis: In the not-too-distant future [1994], a naïve, idealistic young couple enters the music industry. But just when their dreams seem about to come true, they encounter drugs, greed and the dark underside of rock n' roll.Tagline: It's 1994! The Future Is Music and Music Is Their Future!

Synopsis: In the not-too-distant future [1994], a naïve, idealistic young couple enters the music industry. But just when their dreams seem about to come true, they encounter drugs, greed and the dark underside of rock n' roll.Tagline: It's 1994! The Future Is Music and Music Is Their Future!

Featuring:

Here's what happened, as told by those who made it happen...

Part 1: Coby and Iris

Coby Recht: The Apple? Oh boy, that's a long story. But let me try and put it together.Iris Yotvat: As probably Coby told you, we intended it to be a stage show.Coby Recht: I should begin by saying that I'm one of the forefathers of rock and roll in Israel. I got plenty of hits, you know, on radio. And then back in the '70s, I went to Holland—I recorded some three albums there—and then went to Paris and signed with CBS and I had a lot of success over there.Iris Yotvat: Very, very successful.Coby Recht: Especially with one single that sold two million. It was something else. And then I came back here, with Iris. We were married then. And before we got here we spent like six weeks, we had in mind to have this as a rock and roll musical for the stage.Iris Yotvat: It was a good story. It was kind of, let's say, a not very sophisticated story, but I loved the innocence of it. I think it was a little bit ahead of its time—at least in Israel, maybe not in America—in thinking about show business as a kind of a battle between good and evil.Coby Recht: The story was based on this: Back in the '70s, the label that I signed with was Barclay. So I came to know Eddie Barclay; he really believed in me. But there was something there that I couldn't trust. I don't know why, but the guy looked to me like a villain. So Boogalow was based on Eddie Barclay. And I wanted the story to be gray, to be Orwellian. It was supposed to be 1984, but with music.Iris Yotvat: So you have the "good guys"—the hippies, the flower kids—who are thinking about love and peace, and then there is the other side of the coin, the other side of the moon, that is show business and thinking about money and power. So it was a good conflict of the two: the conflict between good and evil.Coby Recht: But it was so expensive that nobody could really raise it up for the stage. It was very expensive. And then finally someone called and told me Menahem Golan was in Israel for a short time.Iris Yotvat: [With a deep sigh]: Menahem Golan.Coby Recht: I called him on a Friday. I remember, because he was leaving Sunday, and he came over the next day. By that time, I had a demo of most of the songs, in Hebrew, and Menahem sat there for four hours, listening. And then after he said, "You have to let me direct it and produce it and you have to be in Los Angeles, right now."Iris Yotvat: That was marvelous. That was just fantastic to think that it was going to be a movie all of the sudden. It was just amazing.Coby Recht: It was good, yes, but what convinced me was this: When Menahem came to my place on that day, he said, "We have to do it on Broadway first!" But then not long after we go to Los Angeles, something else Menahem was supposed to shoot didn't work out...and guess what takes its place?

Part 2: Menahem

Iris Yotvat: I'd never met Menahem before, but Coby knew him from a very, very early age. From when Menahem was not yet a movie director at all.Coby Recht: Oh, yeah. He used to have this children's theater [in Israel]. When I was nine, I used to be his star. So I knew him from them, but I was not in touch with him. Even so, I knew exactly who Menahem was: He never paid the money that was owed. To me, to anyone. One day my father said to him, "What are you doing with the money that you owe him?" And Menahem said, "I'm saving it for him!" Boy, was he a...but on the other hand, there was something there that I liked a lot.Iris Yotvat: I think the fact that he was generous, very generous. When we came to Los Angeles, he gave us his villa to live in. That was the first time in my life that I was in a villa with a swimming pool. And during that time, he went to go live with his cousin, his partner. I mean, a person gives his house for us to live there for a whole month? And to do whatever needed to be done in order to get the script done. I think that was really nice.Coby Recht: Menahem is...there's a book to fill with this character.Iris Yotvat: What he used to do sometimes was put together a poster with the names of stars and a director before he even had a script. And he would go to Cannes with posters and all kinds of things like this and then people would invest in him and then he'd go and get the director and a script and stuff. So he was like that. And he was kind of, let's say, not very delicate or gentle. He was not a gentleman; he was a businessman. And his way of talking was cruel; it was not very soft-spoken. For me, it was difficult to accept him like this. But I had always problems with people from show business.Coby Recht: Anyway, he had me come to Los Angeles. Well, first me and Iris, but then only me. Rewriting the whole thing, making it totally different.Iris Yotvat: Yeah, that was hard. I was frustrated mainly on the content issues where I saw that the whole story of the movie was becoming something that was kind of corny. And we had a small child at this time. I couldn't bring him over, but luckily my mom was a young grandmother and she really helped a lot with babysitting actually.Coby Recht: The first time that I understood I'm in deep shit was when Menahem said, "Where's the action?" Whoa, that was too much.Iris Yotvat: We couldn't do anything anymore. I mean, it was in Menahem's hands. And of course money talks, you know.Coby Recht: "Where's the action?" Come on. It's a small movie. It's rock and roll. And then he said to me, "Eh...Rockin' Horse, Rock n' Roll." So what can you do?Iris Yotvat: But there was one part of this that was wonderful. We worked with George Clinton to translate it and to make it into a script. And working with George was great, I loved it because we were both lyricists. And working with him, cowriting the English version was a very, very wonderful experience for me.Coby Recht: And when I had about 50 percent of the demos done, Menahem said, "Next week we go to London; then we start filming soon." Just like that, you know?And so, just like that, the two of them went to London, where they continued working with George Clinton and started casting the film.

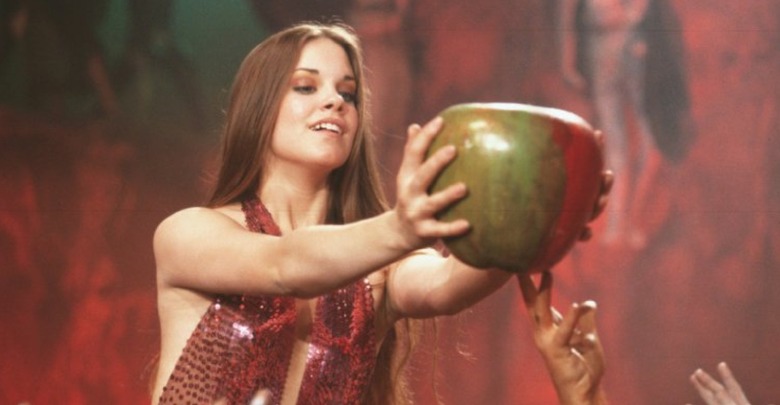

Part 3: A Kind of a Musicality to It

Catherine Mary Stewart: The whole thing was by chance. I was going to this performing arts school in London and one day, after class, I ran into some students from my dance class who were walking away from the studio. I asked them where they were going and they told me about this audition they'd heard about. It was a cattle call audition for dancers, so I tagged along.Coby Recht: Cathy came to the audition as a dancer. I remember I was sitting on this ramp there and she was among like two hundred other girls. And all of the sudden I saw her and I said to myself: This is Bibi. This is exactly what I had in mind when I wrote the script. So I went to Menahem and I called him over to see her. "She looks great," he said.Catherine Mary Stewart: I just, I remember dancing with all these other dancers. And Nigel Lythgoe—he was the choreographer—so, you know, he'd give us these moves. And I noticed this man at the front, framing me with his fingers in a classic movie director way. I didn't know he was doing it towards me, but as it turns out he was.Coby Recht: "But can she sing?" Menahem asked. I don't know, but I'm telling you she's Bibi. "Go downstairs, there's a piano there, and see if she can sing." She was 19 or something and I took her downstairs and the lady could not sing. Could not utter one note. But I had to have her. She was perfect. And I remember going back to Menahem and lying to him, saying that she was a great singer.Catherine Mary Stewart: They gave me some sides, a script, and had me come back the next day to audition for them. And I also had to learn a song to sing, because it was this rock musical. A "futuristic rock musical," as Menahem termed it. So yeah. I came back the next day and I pretty much got the job.Coby Recht: She was so young. She was shocked. She was trembling all over, you know? This was a main role in a movie, and she had come there as a dancer. But I said, "Don't worry, I'll be with you, I'll work on this with you. It'll be okay."Catherine Mary Stewart: It was such a whirlwind. It's hard to remember all the details. But here's one thing I recall: Menahem didn't like my name. It was "Mary Nursall" then. [Mimicking Menahem's thick Israeli accent]: "You gotta change it!" My mother's last name is Stewart—she's Mary Stewart—so I thought that had a kind of a musicality to it. So I ended up changing my name to Catherine Mary Stewart for the movie.Coby Recht: Eventually Menahem realized that Cathy couldn't sing.Catherine Mary Stewart: I had trained a little bit as a singer and I had a decent voice but, you know, everybody else in the movie was a professional singer! They sent me to a voice coach who actually thought I was fine for the movie, but they kind of got cold feet and ended up hiring this terrific professional singer from L.A.Coby Recht: We asked Mary Hylan, and she flew over to do the singing. I told Cathy, "You stick to her and watch her lips." And she dubbed it great.Catherine Mary Stewart: I think they were probably smart to get someone who had an established, strong voice. She had the chops for sure. And the next thing you know, we're in rehearsals, and recording and then flying off to Berlin to shoot the thing.

Part 4: The $4 Million Film That Cost Ten Million Dollars

Catherine Mary Stewart: The one thing I did have going for me with all this stuff was a great deal of discipline. Because as a dancer you need to have incredible discipline. So nothing in terms of the schedule or how much work was an issue at all. [A flicker of laughter.] Except for one time: I misread a call sheet and I thought I had a day off. So I was out all night with some of the other people and I get this frantic call in the morning, saying, "Where are you? You're supposed to be on set." So I showed up really fast, but I literally hadn't had any sleep the previous night. And I got to the set and Menahem was furrrrrrrrrrrious with me. He stormed into the makeup room and he's yelling at me for being so irresponsible and he literally said, "You will never work in the movie business again!" He was so mad at me and he was always very passionate about what he wanted. People had to, you know, he surrounded himself with people who knew how he worked and were willing to work in that way.Coby Recht: I could not be in Berlin at first because I was still in London to mix down [combine all the recorded audio tracks]. And it was crazy. I would get a phone call every day from Menahem. "I need you. I need you now!" "Listen, I can't be in both places." Finally, he said to forget the mix, and so I come out to Berlin, and boy was I shocked. I mean he was shooting this part that never ended up on the screen because it was terrible. It was terrible. There was like 15 dinosaurs on the set. I couldn't believe my eyes. Menahem told me, "This is a million dollars, just this sequence." So I said, "I don't care how much this is, this is ridiculous." I mean, the budget for this movie started with like $4 million. But when we were in London, Menahem used to go like every week to Berlin and come back with another million. And then we got to $10 million. I told him that was a big mistake because it's not supposed to be a big movie.Iris Yotvat: Berlin was hard. It was snowy, it was very cold, and I saw all kinds of scenes that were not [in the script] before. All kinds of corny things. Like the Jewish landlady with chicken soup. You know, things like this? That was not something that I would ever think to put in. I saw all those things, and for me it was kind of Level B movie. Or maybe C or D; I don't know which one. But not A, no not A.Coby Recht: Menahem knew that I hated it. I couldn't agree with it, you know, for like a million years.Iris Yotvat: But, even so, it was crazy to see things, you know, becoming real on the set. That was really fantastic. And also I loved the people that were working with us. The dancers, the actors. Cathy and all those people, really beautiful people. So that was really nice to be in contact with.Coby Recht: For me and Iris, this was our baby. And Menahem...but there was one guy who agree with us: Dov Hoenig, the editor. He was a genius. He was the only one in Berlin that knew what the real thing was about. And I remember I once went to the rushes and Dov was not there. And it happened that Menahem fired him because Dov said one thing: "This is out of focus." This is all he said, and Menahem fired him.Dov Hoenig was replaced by a young editor named Alain Jakubowicz.Alain Jakubowicz: I knew Dov, and he was very stubborn. He's a great editor. But very stubborn. And he was an editor on Menahem's previous movies, and they had had fights before. It was not his first movie with Menahem, and they were fighting on almost every movie. And on that one, they almost were physically fighting. Fistfighting, you know? And Menahem Golan had enough of it. And just wanted to try someone new.Golan knew of Jakubowicz because he had edited the Israeli megahit Lemon Popsicle. Alain Jakubowicz: "I will try that kid," is what Golan said. And that's how I ended up working with him. I was very lucky. I was very lucky because I had come to Israel in '68 when I was 19 years old and the movie industry was starting there. Everything was starting, it was a new country. And I was very lucky because every movie I was editing was turning into gold, so I became, you know, every producer wanted to work with me.Coby Recht: After Dov left, that really broke me down. Because he was our only spiritual partner. What can I tell you? I was just, I didn't know how to react. Especially to the ending. It was too much for me.Iris Yotvat: The ending, that was horrible for me. I mean, God walking up in the air in the sky with this Rolls Royce and all those things? What kind of an ending is that? What kind of a solution is that? I mean, I couldn't understand it. That was too much for me; that really broke me.Coby Recht: Finally, I said to Menahem, "Listen, I'm going back to Israel. I'll get you whatever you want but this is too much, you know?"Alain Jakubowicz: I had a great time, but it was such a weird experience. Especially from the perspective of an editor. I mean, nothing really matched. It was so over the top. the story was kitsch, so unreal you know—but on the other hand, there was a lot of musical cues, which I loved. And I thought that the fun, my fun really, was to cut those musical numbers. I mean, I had a ton of material there. Golan would have five to six cameras for the musical numbers. And don't forget that we were working with film. And I had, really, a million feet. I mean the amount of material...and he was doing that on almost every movie, by the way. Covering it. His movies, the first cut of almost every movie he was directing was four hours long. And you know how many times he was yelling, "That's it, we don't touch it anymore!"Catherine Mary Stewart: Menahem was very passionate about what he was doing. He had very lofty ideas about the project. He thought this was going to break him into the American film industry. It had, you know, all the elements that he thought were necessary at that time. It was the early eighties and there were a lot of musicals. And Menahem thought that was his ticket into the American film industryAfter wrapping production, the film premiered at the 1980 Montreal Film Festival.

Part 5: If You Look Closely Enough, It All Makes Sense

Catherine Mary Stewart: What I heard was, the guy who was running the festival listened to his son who recommended that The Apple open the festival, and so it did.Iris Yotvat: I wasn't there. You know, after it all happened we didn't get any money out of it, so I didn't have any money to go anywhere to see the movie. And nobody sent me a ticket to go there. So...that was it.Catherine Mary Stewart: So The Apple opened the festival and, well, the audience didn't like it that much. And they literally...they were handing out—back then, they were records, vinyl records—and they were handing out vinyl records to people with some of the music on it. And [the audience was] throwing these things at the screen. And literally after the screening, Menahem, he used to tell this story, he was literally suicidal. He literally went back to the hotel and considered throwing himself off the balcony. Because he had so much faith in this movie.Alain Jakubowicz: Menahem was completely destroyed by it. Bad reviews almost everywhere. Because he was sure that he had one of the biggest masterpiece ever done. But, of course, the audience didn't take it that way. And I couldn't blame them because, you know what, either it was too early for its time or it was too, I don't know. It was so kitschy. It was his vision of the sixties, of the hippie movement, of Woodstock, you know? That was his vision of what it was, okay? It was not my vision, it was not the vision of anybody who went through it, but it was his vision. Peace. Love. God. All that. Evil against the Good. That was the message, there was no other message there. It was a message of peace basically, of good will triumph over evil. And that's what he wanted to try and show in the movie. But, you know, it wasn't his generation. He never touched drugs, he didn't know what vision you had when you took LSD. So that was his vision of what he thought represented the sixties. And he was crushed by the reviews. He thought they were wrong. I remember him saying, "It's impossible that I'm so wrong about it." That's what he was saying, okay? "I cannot be that wrong about the movie. They just don't understand what I was trying to do."Catherine Mary Stewart: I don't remember being particularly upset. I was always the one who was like: Isn't this fun, that we get to do this?! But what made me upset was when I heard the story about Menahem that he was so upset.Alain Jakubowicz: Menahem was ready to give up almost at that time. But Menahem was not the kind of person to give up on anything...he loved movies. That was not, by the way, the only musical idea with him. I did another musical later on, Mack the Knife, with Raul Julia [based on Threepenny Opera from 1928]. Great cast, great musical numbers and, again, it doesn't even exist on DVD. I have an old VHS copy, that's all I have. And it was, in my opinion...of course, I remember when he called me in the office to tell me that he got the rights to Threepenny Opera and I asked him if it was going to modernize it—update it a little more. "No, I'm not going to touch a thing. It's going to be Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill and that's it." And I said, "But Menahem, who is going to watch it?" And he says, "Nobody. But you and I will get the Oscar." That was Menahem.Coby Recht: Menahem and I didn't talk for a couple of years after that until we met here in Tel Aviv. He said, "I want you to score [the Golan-directed] The Delta Force." And I said, "Give me the money right now." Because he owed me so much money from before. So he gave me the money, and finally I went to London and scored The Delta Force. He loved it.However, Recht said, Golan later claimed he was forced to replace Recht's score with one by Alan Silvestri.Alain Jakubowicz: I edited The Delta Force. I did, you know, all those movies. And Delta Force was not a bad movie at all. But everything which was coming out from Cannon, it was getting a bad review. Even if film critics didn't see the movie. Once they saw the Cannon logo on the screen, that was enough. You didn't need much more than that. And it's a pity because we came out with pretty good movies during those days. Don't forget, we did Runaway Train and Barfly. One of my favorite movies I edited was Shy People, which was directed by [Andrey] Konchalovskiy. We came out with decent movies as well, but we always were facing the critics. But among a few gems, a lot of crap was done of course. And don't forget that at that time we didn't have cable; we didn't even have VHS when I started, so everything was going on the big screen. And not everything deserved to go on the big screen, but you didn't have any other outlets.Catherine Mary Stewart: Menahem and his partner Yoram [Globus], they were living their dreams. They really, really were. And it worked for a while. They made some money for a while. But I always say there was sort of a chip missing in their American film industry sensibilities. Their movies would have almost all the ingredients, but there was always something missing.Coby Recht: So Menahem and I didn't speak much. But just before he died [in 2014], he called me. He gave me this script to read that he wrote. It was called The Golem, and it wasn't bad. It was very Jewish. But kabbalistic. A crazy thing, but it was written well. And he said, "Give me the main theme!" And I wrote the main theme and he loved it. But then he left us all. It was sad. Because he was a good guy, but he was so crazy.Catherine Mary Stewart: I'm so glad that I got to see him before he passed away. It was at Lincoln Center; they were doing a retrospective on Cannon films. I hadn't seen them in, I don't know, probably the early eighties. And it was really wonderful to see him. He hadn't changed. He was exactly the same. Same guy. But, you know, he was so pleased that he was being acknowledged. And him and Yoram, there had been a falling out—there was a long history there—but they had recently gotten back together and they were hoping to make a bunch more movies. He seemed to be in a good place. And again, I was so pleased to be able to see him.Alain Jakubowicz: I was in touch with him almost 'til the end. Because he always had plans, up until the end. He always said, "Don't take anything, don't work with anybody, because I'm coming to do the next movie with you." Yeah, he believed until the end... Look, he was a producer. He was someone who loved movies. You can debate his taste in movies, but you cannot debate the fact that he was a movie lover.Iris Yotvat: His whole world was in movies.Coby Recht: I remember, when we lived in London, we would watch Western movies every Saturday. And he would get so excited. So excited like a child. And sometimes it would be confusing or unrealistic, and I would say, "This is impossible to understand!" But he would shake his head, while still look at the TV, and say, "No, you're wrong. It all makes sense. It's just a movie. This is a movie."A special thanks to intrepid editor Rick Gershman for staying up late with me to help make sure that this piece reads as smoothly as those interviewed for this deserve.