Quentin Tarantino Is A Terrible Choice For 'Star Trek'

(Welcome to The Soapbox, the space where we get loud, feisty, political, and opinionated about anything and everything. In this edition: why Quentin Tarantino and Star Trek are a match made in hell.)

I'm calling on all of every Star Trek "purist" who claims to have a problem with Star Trek: Discovery to direct their indignation to a piece of news worthy of such emotion — Quentin Tarantino directing a Star Trek movie.

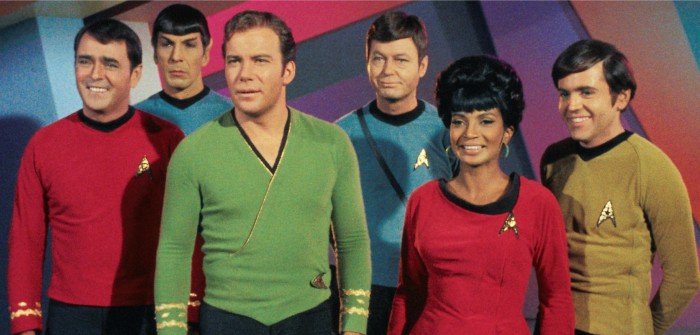

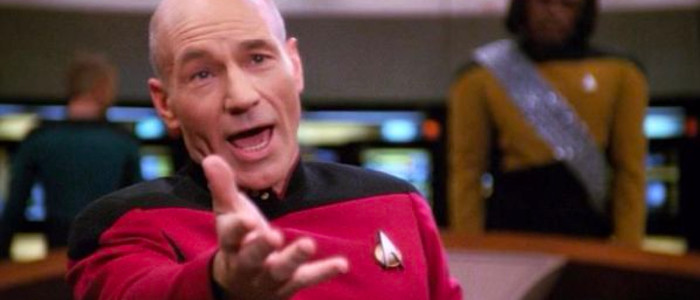

For whatever reason, Paramount has agreed to let Tarantino direct an R-rated Star Trek film, with The Revenant writer Mark L. Smith becoming a prime scriptwriting candidate. The film would be the first R-rated film in Star Trek franchise history. Not only that, but Jean-Luc Picard himself, Patrick Stewart, wants to be on board.

I, for one, am shocked. First, because J.J. Abrams, who has had such a good handle on the Star Trek reboot series up until now, has okayed this unholy union. Second, because Tarantino should have enough self-awareness to know he does not belong anywhere near the Star Trek canon.

Let me play devil's advocate for a second. Perhaps he does have some self-awareness, which is why he's okay with someone else writing a script for a film he apparently wants to direct — this might be the very first time he's relinquished the reins on a film. But still, Tarantino should be nowhere near Star Trek.

It's not because he's not creative, and it's not because he's not talented. Heck, I like some of Tarantino's films, such as the Kill Bill series, the majority of Django Unchained, and Pulp Fiction (a problematic film because his copious use of the N-word, which I'll address later in this post). But there are several reasons why Tarantino should keep his nose out of Star Trek. Let me count the ways.

Star Trek is more than just a “genre” film

For a film and TV series like Star Trek, a director needs a basic understanding of the franchise. As I've written many times in my Star Trek Discovery recaps for this site, the series is at its best when it acts as a case study for how humanity can get along with each other. As Gene Roddenberry said when describing Star Trek:

"Star Trek was an attempt to say that humanity will reach maturity and wisdom on the day that it begins not just to tolerate, but take a special delight in differences in ideas and differences in life forms. [...] If we cannot learn to actually enjoy those small differences, to take a positive delight in those small differences between our own kind, here on this planet, then we do not deserve to go out into space and meet the diversity that is almost certainly out there."

Compare that to how Tarantino described his movies in a 2010 Telegraph interview:

"I think it's one of the strengths of my movies that I work in genre. I like making very, very personal movies, buried inside of genre."

Technically, Star Trek is a genre show, but it behaves as something much more. It behaves as a high allegory — and allegory is something that often seems lost on Tarantino, who is adept at working within a genre but often forgets that one of the most compelling parts of genre films are their ability to comment on contemporary issues in a witty, surprisingly deep way. Often, Tarantino's films don't provide commentary on a larger issue, even in films like Inglourious Basterds, which features a rogue WWII squadron taking down Hitler, and Django Unchained, which aims to tackle America's original sin, slavery, and make a runaway slave the superhero. More times than not, Tarantino's films reflect Tarantino and Tarantino alone — they amplify his first loves: blaxploitation, grindhouse, and the counterculture style found in both genres.

As Benjamin Secher wrote in that same Telegraph profile:

"Although his films are instantly recognizable...they feel united in the manner of products belonging to a carefully controlled brand, rather than by a common heart of personal revelation. Indeed, the most frequent criticism levelled at Tarantino is that his characters lack humanity; their fates may amuse us, but rarely do they move us. No matter how many people die on screen, nobody cries at a Tarantino film."

Tarantino's films are personal in the sense that they showcase him. But by that same token, they are also narcissistic.

Django Unchained is a perfect example of this narcissism on display. We are made aware of Tarantino's interest in exploring America's history of slavery, and in several interviews leading up to the release of the film, he talks openly about how he struggled with if he should be the one to bring such as story to screen. After getting advice from elites in black Hollywood like Sidney Poitier, Tarantino decided to bring his story of a slave defeating the slave owner ensnaring his wife, to the screen.

The film begins hauntingly as we see Django (Jamie Foxx) and other slaves chained together, being led through the wilderness by a slave trader. But as the story goes along, the film becomes less about Django's revenge on the film's big bad, Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio), and more about Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) and his bleeding heart towards slaves. Schultz's pathos reaches its zenith when he — not Django — delivers the death blow to Candie, despite Candie being Django's to kill. Schultz's growing intolerance to slavery slowly showcases Tarantino's penchant for centering films around himself; Schultz is Tarantino's avatar in this lawless world, and through Schultz, Tarantino is able to live out the fantasy of ending slavery and saving black people. He literally becomes a white savior.

If Tarantino is going to successfully write and direct a great Star Trek film, he's going to have to think outside of his narrow grindhouse bubble. There is a way to make a personal film without it becoming self-centered, and somehow, Tarantino is going to have to grow beyond his own ego and point-of-view to understand what a Star Trek film needs. Tarantino is a student of pop culture and he surely knows that Trek's strengths come from uplifting the values of camaraderie, peace over violence, and acceptance over bigotry.

The Values of Star Trek

While Star Trek's focus on equality is the franchise's calling card and one of its building blocks, one part of the franchise's foundation stems from an edict that isn't talked about enough, even though it permeates throughout every Star Trek property. That edict is that there's more strength and more power in numbers than there is alone.

This ideology does draw from Roddenberry's focus on equality, but it also opens the franchise up to challenge not only how its viewers see American politics, but how they see their place in the world as well. It's radical for a show made in an individual-first society like America to preach the positives of working together as a cohesive unit that recognizes each person's differences as their own unique skill sets. Even the Borg — one of the most popular villains in Star Trek — are often described as being evil because of their conformity, but the real reason Starfleet has an issue with the Borg is their unwillingness to recognize other ways of cohesion in other societies.

This nuance of Star Trek is what makes it different from other sci-fi out there. Its respect for everyone's unique gifts and its mission to value those gifts is why the franchise has endured for so long and has entranced so many people from all walks of life. It's why the fair treatment of characters like Geordi LaForge, who is blind, constantly teaches its viewers to see everyone as capable and valuable. It's also what makes it feel like a bad fit for someone like Tarantino, who prides himself on his renegade individualism. So far in his career, Tarantino hasn't proven that he can take on a franchise as cerebral and activist-driven as Star Trek.

These are strengths that are easy to write in a sentence or say in an interview, but they're surprisingly hard to get across in a visual medium without becoming preachy. Somehow, Star Trek manages to do it time and time again. But it's because there's a level of conscientiousness involved — so far, Tarantino hasn't proven that he has conscientiousness. What he has proven is that he uses blunt force with his particular aesthetic in every film he makes.

The N-word

Yes, Mark L. Smith is the current frontrunner to pen the film's screenplay, but Tarantino's going to have his hands all over the script regardless. With that worry in the air, I'll bring attention to the most divisive part of Tarantino's film history — his use of the N-word.

No director has been more linked to the N-word in modern film history than Tarantino. Tarantino has said that he loves saying the word for various reasons, as Gawker recounted. First, in a 1994 interview, he said that when you make a joke with the N-word, you've got to use the word "or it's not funny."

"It's only the dirtiness of it, the nastiness of it, that makes it funny," he said. "So I don't want you to censor the way my characters talk."

Later that year, after Spike Lee called him out on his overuse of the word in Pulp Fiction ("It's not cute," he said), Tarantino gave his political stance on the word to Vibe Magazine.

"My feeling is the word...is probably the most volatile word in the English language. The minute any word has that much power, as far as I'm concerned, everyone on the planet should scream it," he said. "No word deserves that much power. I'm not afraid of it. That's the only way I know how to explain it."

Tarantino has a deep desire to claim blackness, including that incendiary word — he's said before that he feels like he identifies with the word because "it speaks volumes about who I am." To him, the word relates to "somebody who's not to be fucked with." But his incomplete view of "blackness" has warped his mentality so much that he thinks he has the right to say that word and dictate how others use it, or better yet, how others should view his usage of it. Every black person can (and probably has) developed their own opinion on Tarantino's claiming of blackness and his usage of the N-word, but this black person is saying his usage of it is immature and juvenile at best. Him saying the N-word isn't nullifying the word's power so much as it is fetishizing it for Tarantino's own pleasure.

I hope Tarantino wouldn't be that obtuse as to put such a horrible word like that in something as meaningful as Star Trek. But whether it's the N-word or something else, I don't put it past him to include some kind of divisive tactic in the film, especially if it means sticking to his grindhouse/blaxploitation aesthetic. Even in his own films, Tarantino has a penchant for going overboard, as illustrated in the Pulp Fiction scene Lee was referring to, in which Tarantino's character says the N-word way too many times during a five-minute conversation between himself, Jules (Samuel L. Jackson) and Vincent (John Travolta).

Star Trek isn't the property to try something divisive. Star Trek is characterized by a code, something Roddenberry stuck to religiously during his tenure. After his death, his code carried on into the various Star Trek writers' rooms. Even the films, which are much looser than the TV shows ever will be, still stick by tenets of Roddenberry-ism, which is to have core characters get along (or at least attempt to understand each other), to keep said characters as likable protagonists, and to have the script promote finding strength in humanity's differences.

Only recently has Star Trek deviated from Roddenberry's original commandments; in Star Trek: Discovery, some main characters are, in fact, unlikeable, and cursing — another no-no from Roddenberry's book of rules — is now allowed. Even kissing and sex, which was avoided throughout much of Star Trek's franchise history, is now a part of Discovery's modus operandi.

But all of these changes took decades to come by. Star Trek is a franchise that can adapt to the times, but it's also a franchise that, like Starfleet itself, has a set of protocols it likes to follow. When protocol changes, it's momentous and rare. Tarantino, however, is like a wrecking ball of a director. I don't see how his anti-protocol sensibility will mesh well with a franchise that is the equivalent of a Type-A college professor.

Tarantino is part of a bygone era

When I first heard Tarantino was joining Star Trek, I immediately thought of Joss Whedon's failed Wonder Woman script. Both instances already have parallels, even without a script for Tarantino's Star Trek to use as comparison.

First, both Tarantino and Whedon have been able to carve out Hollywood popularity through their work in genre storytelling. Thanks to shows like Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Firefly, Whedon has become known as a writer with supposedly "feminist" sensibilities and supposedly "strong" female characters.

But take a look at that Wonder Woman script of his — even though he's made his name writing female characters, he centers the entire Wonder Woman script around Steve Trevor, turning Wonder Woman into a "Born Sexy Yesterday" trope. Compare that to final version of Wonder Woman. Even though the film is still written by men, the script comes across much more caring and sensitive to Diana herself, and it's clear that this is Diana's origin story, not Steve's. The direction by Patty Jenkins also allows for more of the film's female point of view to shine in a much more authentic way than the original Whedon script ever allowed. On paper, a Whedon-led Wonder Woman should have made sense. However, Whedon proved without a doubt that writing women isn't his strongest suit, at least not any more.

I'm using Whedon as an example to say this: while Hollywood tends to think that "auteur" writer/directors can write and direct anything, that's not always the case. Just because a person can work in "genre" films doesn't mean every genre is for them. Some people excel at certain genres and are worse in others, and that's perfectly fine. Not everyone can be a chameleon (although there are definitely those in the business who are).

For what it's worth, Tarantino is a master of his particular niche, which is taking the coolest parts of B- and C-movies and turning them on their heads in different ways. Pulp Fiction has interesting turns of phrase and indeed, whimsy, that make it worthy of study and dissection. It does present the standard "hit man" movie in a unique innovative way. It's definitely provided movie fans with quotes that are still fun and relevant to this day.

However, Tarantino's strength — creating a niche — has also become his Achilles' heel. Because he, like Whedon, has been rewarded so many years for their particular style and flair, Tarantino has yet to grow his skills beyond what made him famous in the 1990s. The same can be said for other niche directors like Spike Lee and Kevin Smith, who were a part of the same wave of late '80s-early '90s auteur directors that includes Tarantino. The times have changed, as have the demands put on directors. We're no longer in a time where all you had to be was a man with a distinct point of view; nowadays, you have to be a director who not only has a point of view, but can adapt to changing social mores and a volatile political climate.

Tarantino has to face the music that his point of view just might be outdated for today's time. One thing Star Trek has going for itself is its ability to be both timeless and contemporary; there is always something new it can bring to the table while further advancing its thesis of peace among humanity. Would Tarantino's frozen sensibilities fare well within a franchise that is constantly adapting? I don't think so.

What about other directors?

Tarantino has talent, but I doubt he has the type of foresight or worldliness needed to churn out a good Star Trek film. There are tons of directors out there who would be awesome in the director's chair, and for a film like Star Trek, it would behoove Paramount and Abrams to hire directors who can fully understand the racial, cultural, and social issues Star Trek addresses.

Everyone shouts out names like Ava DuVernay and Dee Rees as directors studios should hire more often. I'm going to sound like a broken record, but I think DuVernay and Rees are owed the chance to direct a Star Trek film. First of all, they've already proven themselves — DuVernay is finishing A Wrinkle in Time for Disney, and Rees, who made her name with Pariah, has attracted awards buzz with her latest film, Mudbound. Secondly, they are astute to what makes characters in racially and culturally polarized worlds relatable and likeable. To that end, they are able to pull out unique moments that resonate with all audience members.

Taika Waititi should also be considered for a Star Trek film, and not just because he's been able to tame a beast like Marvel's Thor property. Thor: Ragnarok showed what an "outsider" filmmaker can do with a big budget, but the film also gave larger audiences an introduction to Waititi's charming and heartfelt comedic style, a style which has carried over from his other films like Hunt for the Wilderpeople and the wildly inventive What We Do in the Shadows. While Star Trek often has a professorial air, the franchise also relies on the power of comedy, and Waititi's mix of honest character beats and situational comedy would add the punch of levity Star Trek sometimes needs.

However, if Paramount is set on having Tarantino direct a Star Trek film, so be it. But, to paraphrase his beloved Jules, I dare you to mess this franchise up, Tarantino — I double dare you.