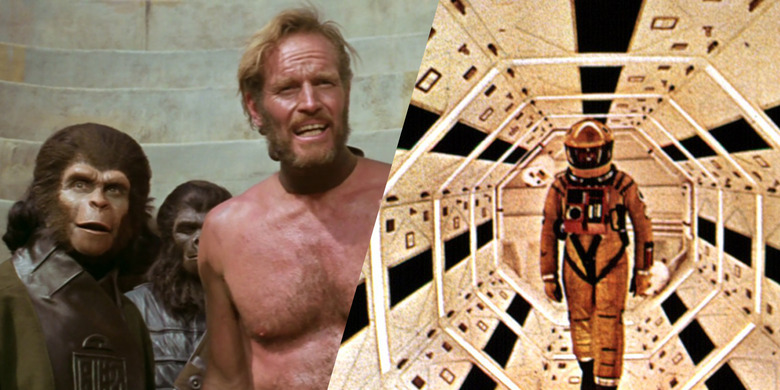

'Planet Of The Apes' And '2001: A Space Odyssey' Turn 50 And They Remain Unlikely Companion Pieces

On April 3, 1968, two all-time greats of the science fiction genre, Planet of the Apes and 2001: A Space Odyssey, hit U.S. theaters. Both films are classics in which astronaut missions go awry, but there are other linking threads. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, the famous "Dawn of Man" sequence shows the beginning of human history, with intelligence alighting within some of our ape-like ancestors, teaching them how to wield bones as weapons. In Planet of the Apes, it's the end of history we see: humankind has nuked itself into near extinction and the world has come full circle to where it is now overrun by primates again.

In addition, both movies honor the genre tradition of using the future as commentary on social concerns of their day, with a major linking thread being the principle of evolution. Let's discuss these two seminal films, their legacy, and how they align and differ in their views of humankind, its place in history, and its place in the cosmos.

Planet of the Apes

Of the two films, Planet of the Apes is arguably much more accessible. Half a century ago, a feature helmed by Franklin J. Schaffner — who would next go on to direct Patton and win an Oscar for it — started a franchise that has remained visible even in recent years with Fox's new reboot Apes trilogy starring Andy Serkis as Caesar (Rise of, Dawn of, and War for the Planet of the Apes).

Divorced from itself as a proven intellectual property in Hollywood, a society of talking apes may seem like a silly premise (though with the specter of swine flu and avian influenza, or bird flu, looming large in the 2000s, the "simian flu" portrayed in the reboot trilogy came off as frighteningly realistic). The talking-apes society is actually a brilliant high concept, however, one that has consistently managed to frame compelling allegories for the human race, even as the Apes series has shifted from outstanding practical effects, make-up and costume design, to motion-capture-driven CGI.

Like so many other good science fiction stories, the original Planet of the Apes and its numerous sequels and prequels — even the absolutely bonkers Beneath the Planet of the Apes, with its singing, nuclear-warhead-worshipping underground mutants — merely serve to reflect the real world back at us in a phantasmagorical way. The focus on apes in these movies belies a very human story, as if returning the audience to its evolutionary roots, holding up a mirror to our more primitive selves and reminding us that as far as we may have come as an ostensibly civilized species, we still have a long way to go.

The choice of Charlton Heston was an interesting one for the role of Taylor, the main character in the original Planet of the Apes. Prior to 1968, Heston had starred in a string of religious films, including but not limited to The Ten Commandments, Ben-Hur, The Agony and the Ecstasy, and The Greatest Story Ever Told, where he played John the Baptist. By today's naturalistic standards, his style of acting — the air of considerable pomp he brought to some of those performances — almost seems like overacting. He was never more hammy than he was as Moses. According to Gore Vidal, who had a hand in the film's screenplay, the crew of Ben-Hur (which I wrote about recently) nicknamed Heston "the big cornpone."

Taylor is a very different character from the kind Heston was known for. He starts out as a misanthrope, waxing philosophical in astronaut voice-over about man making war on his brother and keeping his neighbor's children starving. If anything, he seems glad to escape Earth. After crash-landing on an unknown planet, one of the other astronauts in his crew, Landon, calls Taylor out on his misanthropy, saying he "despised people" back home and "thought life on Earth was meaningless."

We have already heard Taylor dreaming aloud of a different breed of men, "a better one," and here again, he is forced to admit, "I can't help thinking somewhere in the universe there has to be something better than man."

We have already heard Taylor dreaming aloud of a different breed of men, "a better one," and here again, he is forced to admit, "I can't help thinking somewhere in the universe there has to be something better than man."

Thus Planet of the Apes introduces one of the central themes it shares in common with 2001: A Space Odyssey — namely, that humanity in its present state could be a kind of imperfect middle stretch along the evolutionary road. Gritting his teeth while talking (as Heston was wont to do, all the better to chew the scenery by baring those magnificent chompers of his), Taylor takes perverse pleasure in needling Dodge with the hopelessness of their predicament. All in all, he's rather unlikeable, not in line with the traditional Heston hero.

When he is shot in the throat and netted by gorillas on horseback, Taylor is soon forced into a regressive, speechless, cave-man-like state, where he has to fight for what it means to be human. The world of the apes is a theocracy where the terror of taxidermied and lobotomized humans marks them as little more than animals. It was only a year before the release of Planet of the Apes and 2001: A Space Odyssey that the Tennessee law against teaching evolution in public schools was finally repealed. The Scopes Monkey Trial is clearly alluded to in Apes in the scene where Taylor appears before a tribunal of orangutans who strike see-no-evil, hear-no-evil, speak-no-evil poses as they cling to the dogma of their Sacred Scrolls.

In the end, Taylor finally wins his freedom, riding away on the beach with the beautiful Nova (played by Linda Harrison), his dignity as an ambassador for the human race seemingly restored. But then the film pulls the rug out from under him, delivering a delicious twist ending originated by The Twilight Zone's Rod Serling.

It's revealed, of course (spoilers for a 50-year-old movie), that Taylor's time-dilated travels through space landed him not on another planet, some alien ape-world, but rather, on a future Earth where humanity has regressed to a more primitive state while apes have gained ascendancy in the wake of nuclear war. Confronted with this terrible knowledge in the sight of the Statue of Liberty on the beach, Taylor sinks to his knees, pounding the sand with his fists and upbraiding humanity with the lines, "You maniacs! You blew it up! God damn you! God damn you all to hell!"

It's one of the greatest movie twists of all time. Informed by Cold War paranoia about a potential nuclear holocaust, this ending espouses a decidedly pessimistic view of humanity's future. It's also interesting because if you look beyond the trappings of the primate costumes, Planet of the Apes and the series it spawned can be seen in this defining moment as a fundamentally earthbound, human-centric narrative.

The best of the contemporary reboot films, 2014's Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, unfolds like an epic based on real political events, complete with a coup d'etat that changes the course of history. By the time the movie descends into a nightmare vision of apes unloading assault rifles on unsuspecting humans (in a sandbag nest, and then again later, while charging forward on horseback, against a backdrop of flames), it is clear this film is painting a stark metaphor of human tribalism at its worst.

The world is on fire every day with conflict and in the heat of all that, down here on terra firma where we are, it's easy to want to turn off the barrage of bad news and tune out the suffering of others. The best art reminds us of that which we forget to see.

To inspire us with a vision of what could be, what we might be, what the greater universe might hold, science fiction would need to look to the stars. In the world of 1968, it just so happened to do that in a film that ran concurrently with Planet of the Apes in theaters.

2001: A Space Odyssey

There are very few motion pictures in the history of the medium that can match 2001: A Space Odyssey in the scope of its ambition. The few contenders from this decade that do come to mind, like Terrence Malick's The Tree of Life, Christopher Nolan's Interstellar, David Lynch's Twin Peaks: The Return, "Part 8," or even Alex Garland's recent Annihilation, all feel consciously beholden in some way to writer-director Stanley Kubrick. Working with science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke on 2001, Kubrick conceived a space adventure that would trace a long arc from humanity's prehistoric origins to its final evolutionary leap millennia later.

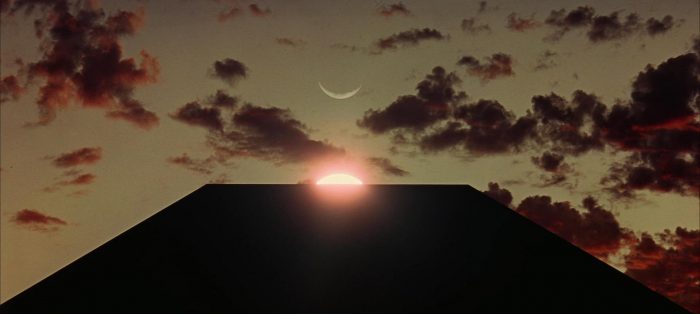

The film begins with a three-minute overture where music plays over a black screen. Do not adjust your television, as the saying goes. In a story where a black monolith presides over human affairs in a godlike way, this black opening feels almost biblical, as if what were are seeing is the time before the Big Bang, when "the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep."

It's the kind of thing that would probably cause AMC to post a disclaimer outside its movie theaters nowadays, otherwise, people wouldn't get it; they'd think something was wrong with their theater projector. 2001 did, in fact, inspire walk-outs when it first started screening. Indubitably, it's a movie that requires patience.

When the first shot of the film finally fades in, it's a different kind of sunrise we see: the sun rising over a crescent earth rising over the dark side of the moon. The appearance of the film's title then transitions us into a sequence boldly proclaimed on-screen as "The Dawn of Man." These words are followed by glimpses of a bone-littered landscape populated by tapirs, leopards with glowing eyes, and tribes of ape-like hominids.

Here again, the viewer must contend with the idea of humanity being an offshoot of a crude family tree, one that is still perhaps growing, if 2001's ending has anything to say about it. Fifty years ago, seeing those hairy hominids after the "Dawn of Man" cue might have been disconcerting for members of the general public who were not yet fully on board with this whole theory-of-evolution thing. In addition to the overturning of Tennessee laws in 1967, petitions affirming official support for evolution among scientists were circulating in 1966, but it certainly had not gained as much widespread acceptance as it has now.

The thing is, the movie also puts forth a view of the universe where beings of higher intelligence can and do intervene in the evolutionary process. It's not so much natural selection as it is cosmic selection that enables one tribe of hominids to master the art of the weapon in the "Dawn of Man" sequence. For whatever reason (maybe no reason at all other than random timing), the monolith manifests itself to that tribe. Is it survival of the fittest or survival of the luckiest: those blessed by an alien presence, some extraterrestrial ex machina with the ability to trigger evolutionary jumps?

Ridley Scott's Prometheus, another film whose reach toward 2001 exceeds its grasp, would depict a similar sort of cosmic intervention beside a waterfall in 2012 (the year the world was supposed to end, remember?) However, in 1968, it feels like something that could have potentially made the scientific community bristle, almost as much as creationists would have bristled at seeing a dawn of man where the men were all wearing gorilla suits.

The first time I saw it, as an opinionated teenager with less regard for cinema's sacred cows, I dismissed 2001: A Space Odyssey as somewhat boring and overrated. The pulpy thrills of Planet of the Apes were more my cup of tea. I imagine other minds caught up in the kinetic energy of youth might have a similar reaction to these movies today. Maybe 2001 is just one of those films where your blood has to thin out and you have to age into it a little before you can develop a real appreciation for it.

I initially had a hard time surrendering myself to the film's glacial, documentary-like pace and diffuse storytelling manner. It's oddly structured: after the Dawn of Man sequence, it takes its time setting up the character of Dr. Floyd Heywood, only to drop his story abruptly and pick up a new plot line with the Discovery One space mission. No sooner does it weave these two strands back together than it sees fit to unravel the tapestry once again as it moves toward "Jupiter and beyond the infinite."

For me as a teen, the most interesting element of the film was HAL 9000, the artificially intelligent computer whose one red lip-reading eye has seen him linked to the figure of the Cyclops in Homer's The Odyssey. Technology and all its myriad wonders and dangers are certainly at the forefront of 2001: A Space Odyssey. If you watch the movie on a tablet, you'll be watching the film that predicted that very form of technology, not to mention things like video chat and the moon landing.

It was 1969, the year's after Planet of the Apes and 2001: A Space Odyssey were released, that Apollo 11 landed on the moon ("if you believe ... they put a man on the moon" ... and Kubrick didn't fake the whole thing. I believe the former, the documentary Room 237 notwithstanding.) Science was advancing, but its forward charge toward the new millennium brought new existential concerns where we were forced to reexamine our place in the universe and how technology might come to rule our very lives.

In 2018, it almost seems like we are at a point now where civilization would collapse if a series of electromagnetic pulses destroyed the Internet and all our electronics. What would we even do with ourselves if that happened? Would we eventually revert to speechless brutes clad in loincloths like in Planet of the Apes?

Nowhere is the prospect of losing control to technology more frightening than in the scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey when the two awake astronauts on board Discovery One realize that every aspect of their ship is under HAL's control. When the computer with a man's name starts to behave suspiciously and then exert his own will outright, the movie ventures into the realm of horror, exemplified by the chilling quote:

"Open the pod bay doors, HAL."

"I'm sorry, Dave. I'm afraid I can't do that."

Apart from this, the music of György Ligeti also makes 2001: A Space Odyssey sound like a horror movie at times. It assigns a great and terrible awe to the monolith. No wonder Gareth Edwards recycled some of that music for the H.A.L.O. jump scene in Godzilla.

If any of this sounds like superficial reading of 2001, like it's not really getting at the core of the thing, it's only because horror and technology and the horrors of technology were all I could see a young person. The movie would not reveal itself to me in deeper ways until I revisited it many years later as an adult.

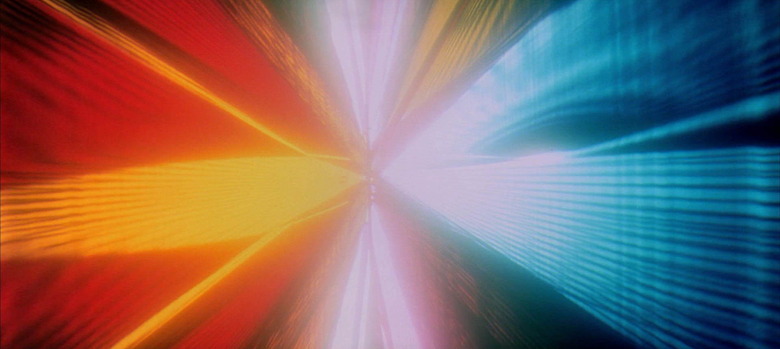

Through the Star Gate

In an interview with Rolling Stone, Kubrick once said of 2001 that "on the deepest psychological level the film's plot symbolizes the search for God, and it finally postulates what is little less than a scientific definition of God." It's clear from other interviews that his idea of God, such as it were, hewed closely to Clarke's oft-cited third law: "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic." Kubrick appears to have seen God not as a theistic concept — some divine, all-powerful Creator — but as a higher evolved form of life that humans lacked the capacity to understand.

Clarke's companion-piece novel, written in tandem with the script for the film, communicates this idea more clearly. Yet it almost seems antithetical to the spirit of 2001 to use the novel or Kubrick's quotes as a means of explaining it. To explain it too much is to run the risk of reducing it.

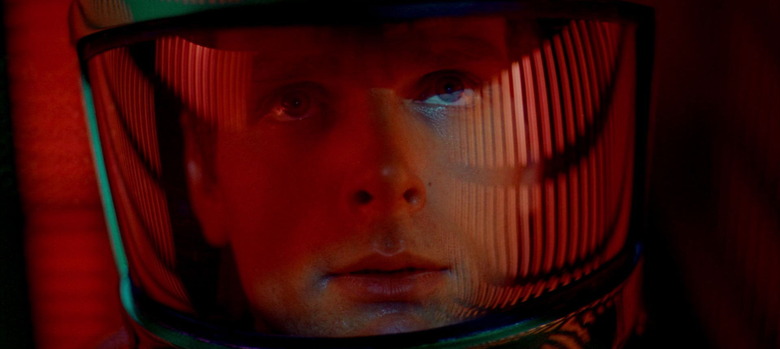

This is a movie that strikes at the subconscious, utilizing sound and imagery as a kind of visual poetry. It's tempting to see it as deliberately opaque, but the film's ambiguous nature comes as more of a byproduct of its lack of dialogue. The first spoken line does not come until 25 minutes into the movie. 21st-century films like Dunkirk or even There Will Be Blood with its 15-minute wordless opening feel heavily indebted to 2001, Kubrick's triumph of pure visual storytelling. Whether it be a piece of classical music or the protracted sound of an astronaut breathing in his suit in space, Kubrick was less interested in verbalizations than he was in elemental sounds coupled with evocative moving pictures that would appeal directly to the brain's irrational side, where the imagination is seated.

This poetic quality, the symbolism at play, is a big part of what helps the movie maintain its raw power half a century later. Adhering to Shakespeare's idea that "the play is the thing," you could watch 2001: A Space Odyssey in a total vacuum without anyone telling you what it means, and it would lend itself to any number of interpretations. Yet the movie also plays upon certain basic fears and universal truths of the human condition, such as aging and death. It's not quite Cain and Abel, but the scene where the hominids take back their watering hole using those weaponized bones does hint at the "ignoble savagery" that Kubrick saw in humanity and that he would soon explore in great depth with the ultraviolence of his next feature, A Clockwork Orange.

The scene where the astronaut Bowman, played by Keir Dullea, enters the mainframe and disconnects HAL's higher brain functions is a harrowing depiction of a sentient being losing its awareness. In a very literal fashion, Bowman strips HAL of his memories, sliding memory blocks out of the computer's brain, sending him winding down into the abyss until all that remains is a slo-mo children's song. The scene stages a vivid mimesis of what happens in our own brains at the point of death: how a person's life flashes before their eyes, synapses firing off last echoes of what was important to them.

With Planet of the Apes fresh in mind, it's hard not to think of the lobotomized Landon during this scene.

On the other side of the Star Gate — in a brightly lit neoclassical bedroom that looks like part of the same house as the bathroom in The Shining — Bowman himself has to suffer the indignity of watching himself grow older. The scene offers yet another visual representation of something that resonates deep in the mind on an instinctual level: namely, the ravaging effects of time, how it skips ahead fast and before you know it, your life is gone.

When Bowman is an old man on his deathbed, the monolith, that persistent emblem of a cosmic intelligence greater than our own, appears at the foot of the bed. Bowman stretches out his finger toward it in a way that mirrors Michelangelo's Creation of Adam, the fresco painting on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. He is then transfigured into the Star Child, an angelic being that floats toward Earth and watches over it from a translucent space bubble.

The cumulative effect of moments like these is to create a chain of primal responses in the viewer. 2001: A Space Odyssey engages the imagination before the intellect, and it does so in powerful ways. It is not always easy to understand or articulate what the actual movie (considered separately from Kubrick and Clarke's submerged artistic intent) is trying to say. Is it a hopeful ending that sees the Star Child hovering over Earth, pivoting its eyes until it is looking directly at the camera and the screen cuts to black?

I think it is. I think that's what distinguishes 2001 from the more blatantly cynical Planet of the Apes. I think it's an uncharacteristic gasp of grand optimism in Kubrick's earlier filmography before we were treated to A Clockwork Orange and everything that followed thereafter.

But I could be wrong. Maybe the Star Child's arrival near Earth's atmosphere signals an impending extinction event for humankind. Maybe it means life has moved beyond homo sapiens at that point, and the feeble remnants of humanity down on the planet's surface are in for another apocalypse like the one that ushered in the Planet of the Apes.

If it's true that "the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function," then perhaps 2001's Schrödinger's-Star-Child ending can simultaneously fulfill both readings, with optimism and pessimism co-existing in the movie on the same level plane. Perhaps that's what makes the movie such a genius work, one that has often ranked in the top ten films of all time in cinematic polls.

Time will tell which reading has more bearing on the real world, but unless we nuke ourselves and all trace of movies into oblivion, or unless the Internet becomes artificially intelligent and decides to purge humans and their culture from the face of the planet, then Planet of the Apes and 2001: A Space Odyssey will probably outlast us all by another half-century or more. Just remember: the Star Child watches.