'Mirai' Review: An Intimate And Fantastical Trip Through Time

Mirai is a movie utterly without pretension. And believe me, it teeters on that precipice — Mamoru Hosoda's latest film has got all the elements of "important art" meant to challenge and excite its audience: a slow-burning pace, a fantastical time travel plot, and sequences that experiment with animation and reality. But everything about Mirai is deeply sincere.

That may be because Mirai is clearly Hosoda's most personal film yet. The Japanese anime auteur has always injected a little of himself in each of his films — the frantic Summer Wars reflected his pre-wedding anxieties, the folklorish The Boy and the Beast chronicled his worries about fatherhood. But with Mirai he takes a slightly different approach, taking on the POV of his young son.

Mirai is a sweeping family epic told through the perspective of a flawed young protagonist that no one will particularly like except for perhaps Hosoda. The 4-year-old Kun is a boy prone to tantrums and random acts of childish cruelty at his new baby sister who has just arrived at their home. Simmering with envy at his attention-hogging sibling, Kun stumbles into a magical garden that acts as a gateway through time. There he meets the teenage version of his baby sister, Mirai, which coincidentally in Japanese means "future." Together they embark on a journey through their family history, befriending Kun's mother as a mischievous young child who likes to wreak wanton household havoc or going on a motorcycle ride through the country with Kun's great-grandfather in pre-World War II Japan.

The film seamlessly switches between mundane moments and dreamlike fantasies, as Kun gets glimpses of his family's sprawling lives and the legacies they leave — though not fully understanding the scope of those existences. It's a premise not unlike Don Hertzfeldt's groundbreaking Oscar-nominated short World of Tomorrow, which explored the meaning of humanity through surreal stick drawings and strange, stilted dialogue. Hosoda and Hertzfeldt even share similar inspirations for these films — basing their characters on their real-life relatives. But rather than exploring the weighty meaning of life and existence, Hosoda prefers to hone in on the naturalistic dynamics of his central family. Because as much as I like to get caught up in the metaphysical meaning of it all, Mirai doesn't take itself half as seriously.

This movie is funny, folks! Wrapped in this meditation on time and memory is a kooky family comedy that manages to bring levity to the movie while adding depth to the central characters. Hosoda has a knack for finding the innate comedy in life, depicting a family that in other hands would come off as cartoonishly absurd. The father is an accomplished architect but a bit of a hapless parent, stumbling to take care of baby Mirai as he works on deadline. The mother, who in another film might be depicted as a shrill nag, is an exhausted perfectionist who through Kun's journeys, was revealed to have quite a wild side as a kid. Just as Kun is almost irritatingly real, the nameless father and mother are as close to living, breathing people as can be rendered in animation.

The exception to this being the titular Mirai. The time-traveling teenager is more enigmatic envoy than actual human being, one of the various fantastical characters supposedly dreamt up by Kun. There's the flamboyant European prince who is actually the personification of the housedog Yukko, and there's even a brooding teenage Kun who frostily berates his 4-year-old self when he finds himself lost at a train station. But the divide between the mundane and the magical realism is never jarring, so elegant is Hosoda's direction.

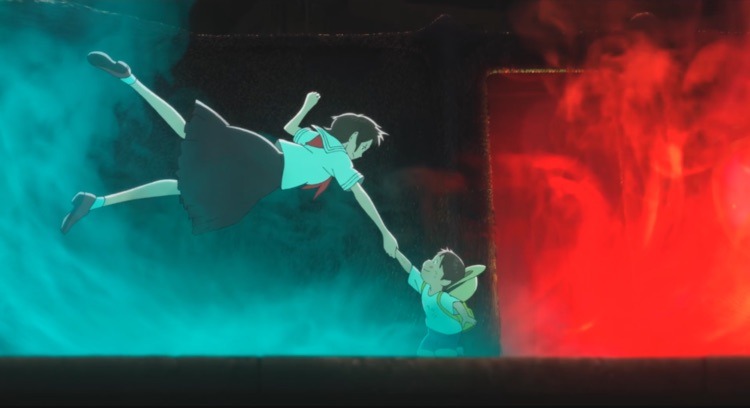

Only one sequence sticks out like a sort thumb in Mirai, but it's with purpose. Hosoda switches up his animation style in a scene that finds Kun trapped in a nightmarish, Kafkaesque train station — the sinister conductor and the uncaring adults appearing in unnatural cut-out animation style that is almost frightening in its suddenness. It's an unusually bold display from Hosoda, who usually sticks to his fluid, soft visual designs, but one that is particularly faithful to keeping the POV of the young Kun.

Hosoda is one of the rare anime filmmakers to understand the poetry of everyday life. Though his films have the same humanist approach, he's never recycled a premise or a family type, rather Mirai feels like an evolution of the recurring themes of family and memory that he has frequently returned to. It's a deeply personal and surprisingly universal story that is easily one of the best animated films of the year.

Rating: 9 out of 10