How Did This Get Made: Masters Of The Universe (An Oral History)

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

He-Man + Skeletor – Everything You Loved About The Toys and TV Show = How Did This Get Made?!?!

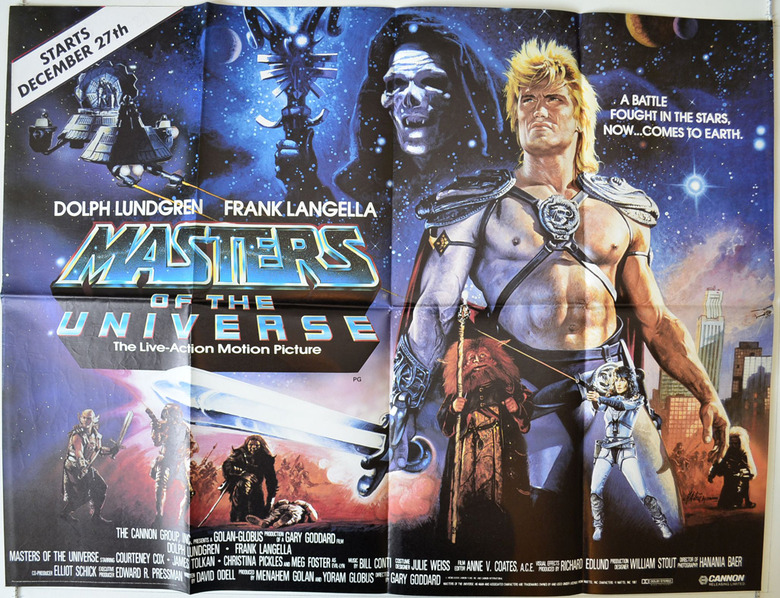

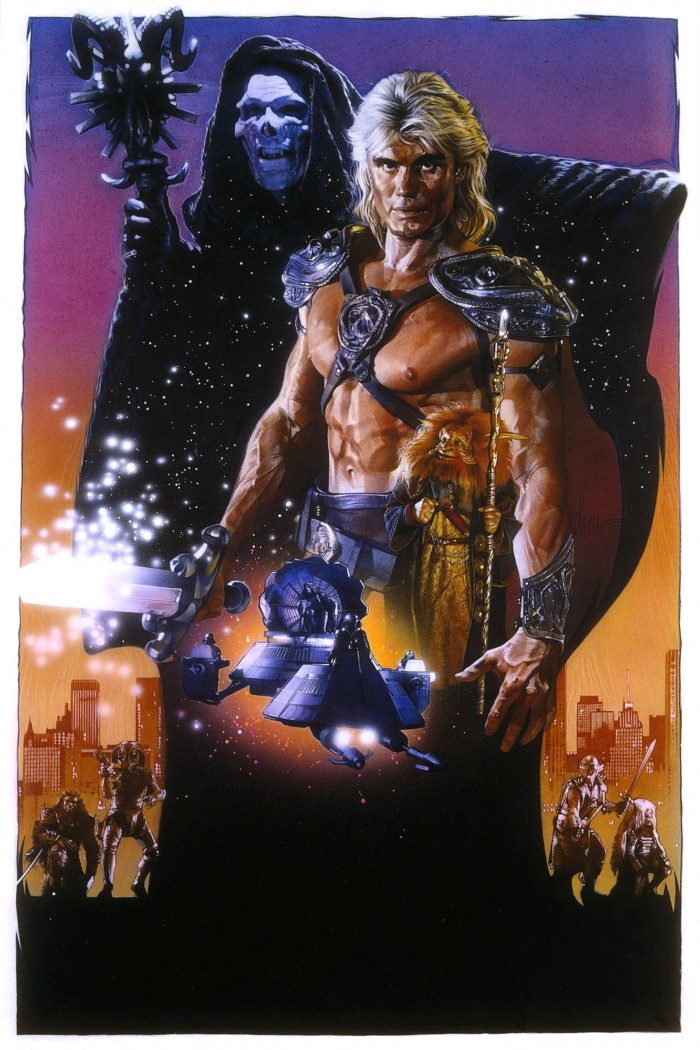

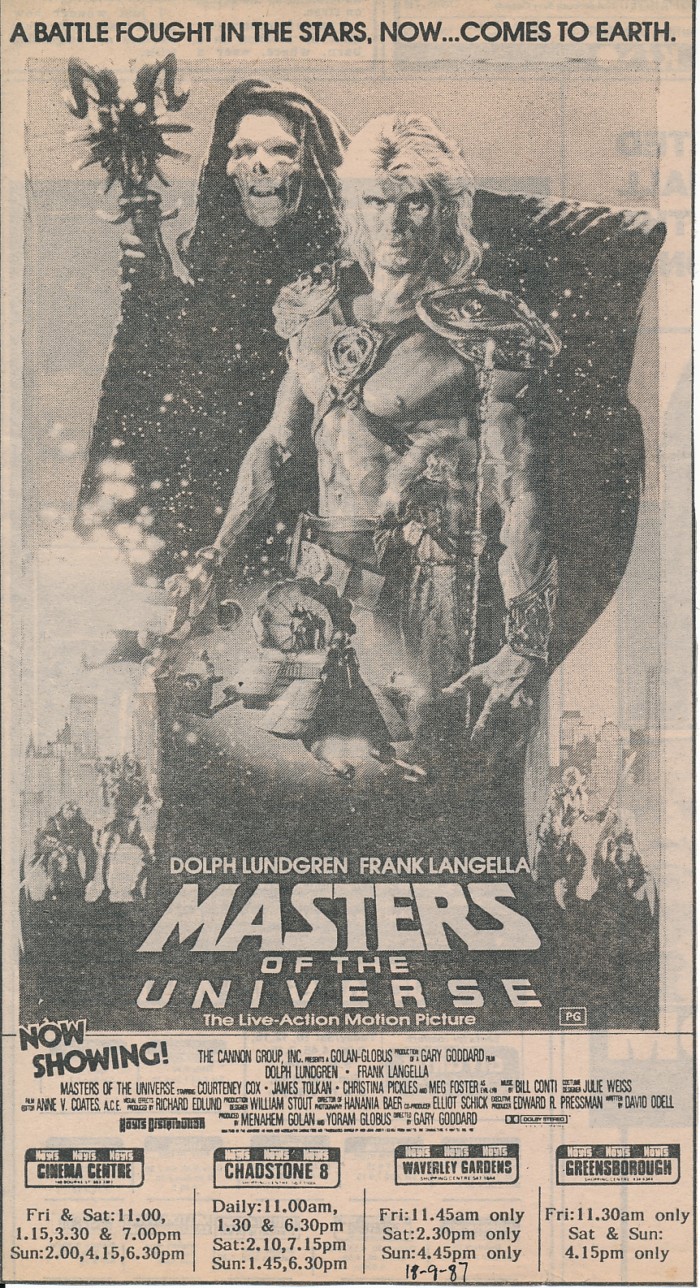

Nobody sets out to make a bad movie. But the truth is, it happens all the time. And every time it does, there's a fun misadventure and cautionary tale lurking somewhere behind the scenes. This is that story for the 1987 live-action He-Man movie Masters of the Universe.

Tagline: A Battle Fought In The Stars...Now Comes To Earth

During the late 70s and early 80s, toymaker Mattel—best known for Barbie—was struggling mightily in the boys action figure space. Without a hit product on the horizon, they were a distant third to Hasbro (which had GI Joe) and Kenner (Star Wars). That would all change, however, in May of 1982 when Mattel introduced a bold new toy line: He-Man and the Masters of the Universe. By the end of that year, He-Man had become the most popular toy on the market.

To capitalize on the pandemonium (and also to keep driving it along), Mattel soon brought this intellectual property out into other mediums. There was a TV show, a pair of animated movies, a traveling live-action show and a line of comics published by DC. All of these things helped build the brand and increase sales. Given this track record, there were high hopes when a live-action movie adaption called Masters of the Universe was released in August 1987. Unfortunately, however, the film did not perform as expected—earning only $10 million at the box-office—and, after three weeks, Masters of the Universe was pulled from theaters nationwide.

How could this have possibly happened? How could a film based on such a hot property—and starring such a hot young actor—resulted in such an unfortunate fate? Was it really such a bad movie? Or, looking back, were there other factors at play?

Here's what happened, as told by those who made it happen...

PROLOGUETom Kalinske: Did I ever tell you the whole story with Star Wars? This one really is bizarre. It takes place some time in the 70s, back when I was at Mattel. It must have been a year or so before the first film came out, and we were presented with the concept of Star Wars.At the time, George Lucas was seeking an upfront fee of $750,000 for the rights to manufacture toys based on the film. Tom Kalinske: The decision, ultimately, came down to Ray Wagner, who was the president of Mattel. And Ray, he was one of the reasons why I joined the company in the first place. Dynamic and smart, he was a very impressive guy. Really hammered into us that you need to think about every aspect of a toy. Not just the design, but the packaging, the advertising and everything else. Anyway, so we have this meeting with George Lucas' agent, and we all come away impressed by what we've seen. Even Ray, he liked what he saw. But in terms of Mattel doing the toys, here's what he said: "Movies never work. Get me a good TV show instead. Television shows are seen weekly—they impact over and over—versus a movie that just comes out one time." And so, in the end, Ray passed on licensing Star Wars.

PROLOGUETom Kalinske: Did I ever tell you the whole story with Star Wars? This one really is bizarre. It takes place some time in the 70s, back when I was at Mattel. It must have been a year or so before the first film came out, and we were presented with the concept of Star Wars.At the time, George Lucas was seeking an upfront fee of $750,000 for the rights to manufacture toys based on the film. Tom Kalinske: The decision, ultimately, came down to Ray Wagner, who was the president of Mattel. And Ray, he was one of the reasons why I joined the company in the first place. Dynamic and smart, he was a very impressive guy. Really hammered into us that you need to think about every aspect of a toy. Not just the design, but the packaging, the advertising and everything else. Anyway, so we have this meeting with George Lucas' agent, and we all come away impressed by what we've seen. Even Ray, he liked what he saw. But in terms of Mattel doing the toys, here's what he said: "Movies never work. Get me a good TV show instead. Television shows are seen weekly—they impact over and over—versus a movie that just comes out one time." And so, in the end, Ray passed on licensing Star Wars. CUT TO: 5 YEARS LATERPart 1: Rise of the He-MenTom Kalinske: Going into the 80s, Star Wars had taken off and GI Joe—over at Hasbro—had come back with a bang. Meanwhile at Mattel, we didn't have a strong male entity at the time.Joe Morrison: Mattel was looking for new concepts in Boys. We had licensed some properties but, you know, nothing really outstanding.Tom Kalinske: We had done a character called Big Jim, which was mildly successful in the early 70s, but it didn't last long. What we really needed to do was build a brand from scratch.Joe Morrison: Towards the end of 1980, I took over as VP of Marketing for the Boys Division at Mattel. And, at the time, there was big research project going on that Ray Wagner had been pushing.Tom Kalinske: We were trying to come up with something that could do for boys what Barbie did for girls. So we tested all sorts of things. Police characters, space characters, monsters, you name it. Until eventually we narrowed it down to a few concepts.Joe Morrison: One was an army theme, a la GI Joe. One was a futuristic space theme, a la Star Wars. And the third was what we were calling a "Barbarian theme."

CUT TO: 5 YEARS LATERPart 1: Rise of the He-MenTom Kalinske: Going into the 80s, Star Wars had taken off and GI Joe—over at Hasbro—had come back with a bang. Meanwhile at Mattel, we didn't have a strong male entity at the time.Joe Morrison: Mattel was looking for new concepts in Boys. We had licensed some properties but, you know, nothing really outstanding.Tom Kalinske: We had done a character called Big Jim, which was mildly successful in the early 70s, but it didn't last long. What we really needed to do was build a brand from scratch.Joe Morrison: Towards the end of 1980, I took over as VP of Marketing for the Boys Division at Mattel. And, at the time, there was big research project going on that Ray Wagner had been pushing.Tom Kalinske: We were trying to come up with something that could do for boys what Barbie did for girls. So we tested all sorts of things. Police characters, space characters, monsters, you name it. Until eventually we narrowed it down to a few concepts.Joe Morrison: One was an army theme, a la GI Joe. One was a futuristic space theme, a la Star Wars. And the third was what we were calling a "Barbarian theme." The original prototypes for the trio of toys that would eventually become He-Man were created by a talented Mattel designer named Roger Sweet. He presented his work to the company's executives at a product conference in December 1980. According to Sweet's memoir, Mastering The Universe, this was the third such conference that year dedicated to finding a male action figure line. "With the conference ending," Sweet describes, "...[Ray Wagner] pointed at the He-Man Trio. 'Those have the power,' Wagner said."Joe Morrison: As the product line developed, He-Man was always just the test name—it was "Star Wars 2," "GI Joe 2" and "He-Man"—but nobody in management wanted He-Man as a name. So it was just this placeholder that nobody wanted. But I did, I knew it was right. And when I was a little boy, my uncles used to call me He-Man all the time so I just yessed everybody to death—yes, we'll make a change, yes, it'll be revised eventually, don't worry!—knowing full well that I didn't want to change anything. Nope, this is going out as He-Man.

The original prototypes for the trio of toys that would eventually become He-Man were created by a talented Mattel designer named Roger Sweet. He presented his work to the company's executives at a product conference in December 1980. According to Sweet's memoir, Mastering The Universe, this was the third such conference that year dedicated to finding a male action figure line. "With the conference ending," Sweet describes, "...[Ray Wagner] pointed at the He-Man Trio. 'Those have the power,' Wagner said."Joe Morrison: As the product line developed, He-Man was always just the test name—it was "Star Wars 2," "GI Joe 2" and "He-Man"—but nobody in management wanted He-Man as a name. So it was just this placeholder that nobody wanted. But I did, I knew it was right. And when I was a little boy, my uncles used to call me He-Man all the time so I just yessed everybody to death—yes, we'll make a change, yes, it'll be revised eventually, don't worry!—knowing full well that I didn't want to change anything. Nope, this is going out as He-Man. Over the next several months, the concept evolved a great deal. Additional heroes were created—like Teela, Stratos and Man-at-Arms—evildoing foes were developed—like Skeletor, Beast Man and Mer-Man—and cosmetic changes were continually made to Mattel's chiseled master of the universe—like changing He-Man's hair color from brown to blonde to more closely resemble Tom Kalinske. (And to exude, like Kalinske, a kinder, breezier attitude.) Developing a likeable, I-want-to-be-him type of hero was pivotal to crafting the kind of story that could entice kids to enter Mattel's unique new universe.Tom Kalinske: I think that the storytelling element was the most important part of it all. We needed to create a series of great stories—as well as a place where kids could imagining those stories happening—and we were fortunate to have some great writers involved in it. Joe Morrison himself was a very good writer, so that helped a lot too.Joe Morrison: I also felt that we needed to do something that was distinctly different in terms of pricing and size. I mean, when you're dealing with young kids, that perception of feeling—the look, the texture, the overall impact—is very important. So I felt we would be making a big mistake if we tried to do everything the same size as what was in the marketplace for GI and Star Wars. Three inches, I think. So we needed to do something bigger, something different.Tom Kalinske: With Masters of the Universe, it was all about doing things differently. That was our only chance, really. And with the final Star Wars film coming out in '83, we thought the timing was right.Joe Morrison: Then probably the next most important thing we did was the commercial. We had a father walk into the living room and see his son playing with action figures on the floor. Then something catches the father's eye and he says, "Hey, who's the big guy with the muscles?" And it had a couple of messages:

Over the next several months, the concept evolved a great deal. Additional heroes were created—like Teela, Stratos and Man-at-Arms—evildoing foes were developed—like Skeletor, Beast Man and Mer-Man—and cosmetic changes were continually made to Mattel's chiseled master of the universe—like changing He-Man's hair color from brown to blonde to more closely resemble Tom Kalinske. (And to exude, like Kalinske, a kinder, breezier attitude.) Developing a likeable, I-want-to-be-him type of hero was pivotal to crafting the kind of story that could entice kids to enter Mattel's unique new universe.Tom Kalinske: I think that the storytelling element was the most important part of it all. We needed to create a series of great stories—as well as a place where kids could imagining those stories happening—and we were fortunate to have some great writers involved in it. Joe Morrison himself was a very good writer, so that helped a lot too.Joe Morrison: I also felt that we needed to do something that was distinctly different in terms of pricing and size. I mean, when you're dealing with young kids, that perception of feeling—the look, the texture, the overall impact—is very important. So I felt we would be making a big mistake if we tried to do everything the same size as what was in the marketplace for GI and Star Wars. Three inches, I think. So we needed to do something bigger, something different.Tom Kalinske: With Masters of the Universe, it was all about doing things differently. That was our only chance, really. And with the final Star Wars film coming out in '83, we thought the timing was right.Joe Morrison: Then probably the next most important thing we did was the commercial. We had a father walk into the living room and see his son playing with action figures on the floor. Then something catches the father's eye and he says, "Hey, who's the big guy with the muscles?" And it had a couple of messages:

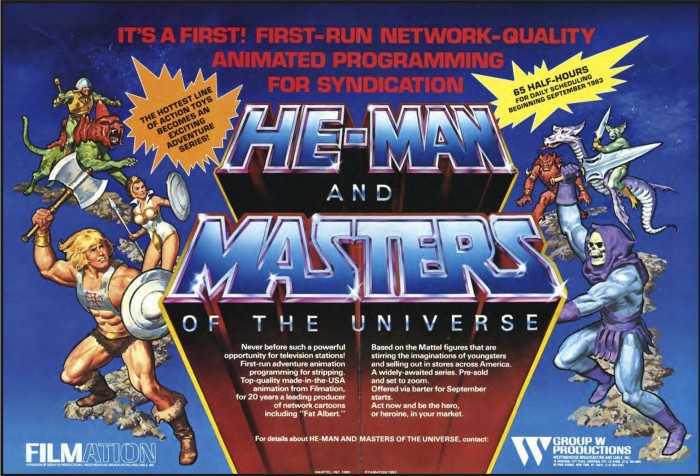

Tom Kalinske: Unlike girls, boys needed a more structured play environment. They didn't need just an ideal character to look up to—like Barbie is for girls—they needed a structured world within which they could play.Joe Morrison: So we had Castle Grayskull, which was designed with a light side to it and a dark side to it. That of course, was in the commercial as well. And then the other thing that we had in the commercial that I thought was important was the music. When I was talking to the agency, I said, "I want music behind this thing that is Gregorian. Like a Gregorian Chant that you hear in church." [In a booming baritone] Heeee-Maaaan, Heeee-Maaaan. Within two days, I could hear my sons and their friends running around and shouting: Heeee-Maaaan, Heeee-Maaaan. That's when I said to myself, "Okay, I think we got something."Tom Kalinske: The toy became very successful, very quickly.Joe Morrison: When we got the go-ahead from management to do the original toy line, we put in an estimate of, like, $12 million in sales. Well, we didn't even release the toy until May of that year and we wound up doing $32 million. These were significant numbers in 1982.Tom Kalinske: By the power of Grayskull! Joe Morrison: To promote the line, we would have these in-store appearances of the characters. And I remember one day, we got a call from a police department in Florida. Tampa, I think. And the police called to tell us that the highway was all blocked off because there were so many kids trying to get there. And that went on around the country.Tom Kalinske: Now, around this time I had a meeting with Art Spear and he sneered, "Yeah, maybe that's successful. But you'll never have a TV show so this won't go big." That made me really mad. I took that as a challenge.Joe Morrison: We took the idea out to a few networks. But they weren't really into it. A TV show based on an action figure? No, it was supposed to be the other way around.Tom Kalinske: The networks weren't interested in this thing. Fine. So we went out and met with different animated producers. And Lou Scheimer—over at Filmation—he was interested in working with us. So we made a deal with them to create 65 episodes. Mattel was gonna put up $3.5 million and Westinghouse [who had acquired Filmation in 1981] would also put up $3.5 million.Joe Morrison: When we originally got into the deal, I think it was the Christmas before we got started, I had hired a writer by the name of Michael Halpern just to do a bible for us. We just paid that out of our brand budget. So within those guidelines, that's what we told Filmation we wanted. So we had that, plus a lot of the story had been told in advertising and there was also a strong personal relationship between us and Lou.

Joe Morrison: To promote the line, we would have these in-store appearances of the characters. And I remember one day, we got a call from a police department in Florida. Tampa, I think. And the police called to tell us that the highway was all blocked off because there were so many kids trying to get there. And that went on around the country.Tom Kalinske: Now, around this time I had a meeting with Art Spear and he sneered, "Yeah, maybe that's successful. But you'll never have a TV show so this won't go big." That made me really mad. I took that as a challenge.Joe Morrison: We took the idea out to a few networks. But they weren't really into it. A TV show based on an action figure? No, it was supposed to be the other way around.Tom Kalinske: The networks weren't interested in this thing. Fine. So we went out and met with different animated producers. And Lou Scheimer—over at Filmation—he was interested in working with us. So we made a deal with them to create 65 episodes. Mattel was gonna put up $3.5 million and Westinghouse [who had acquired Filmation in 1981] would also put up $3.5 million.Joe Morrison: When we originally got into the deal, I think it was the Christmas before we got started, I had hired a writer by the name of Michael Halpern just to do a bible for us. We just paid that out of our brand budget. So within those guidelines, that's what we told Filmation we wanted. So we had that, plus a lot of the story had been told in advertising and there was also a strong personal relationship between us and Lou. John Weems: Once the deal was signed, Mattel created a new Entertainment Division because, you know, they'd never done a cartoon or anything like this before. So about a month after I got to Mattel, Joe Morrison—who was my direct boss—he called me into his office and said, "We're going to do a He-Man television show. So why don't you come over and be the director of entertainment?" Well, I had come to California because I was very interested in the entertainment business and figured that Mattel would at least get me closer to that and allow me to do what I knew best: brand marketing. So, for me, this was a perfect opportunity. That said, it was pretty risky to put our money where our mouth was.Joe Morrison: It was risky, yes, but the way we structured the deal it was less risky. We syndicated the show and for our "participation on the production," if you will, we received two-minutes a week of advertising for Mattel which we used for several of our other brands. The advertising that we got for our part of the deal on that thing was so undervaluedJohn Weems: There was a lot of concern about—between the show itself and the spots we were running—with critics asking: is this just an advertisement for the toy line? We eventually had Peggy Charren and Action for Children's Television lobbying against us. It's ruining our children's minds!

John Weems: Once the deal was signed, Mattel created a new Entertainment Division because, you know, they'd never done a cartoon or anything like this before. So about a month after I got to Mattel, Joe Morrison—who was my direct boss—he called me into his office and said, "We're going to do a He-Man television show. So why don't you come over and be the director of entertainment?" Well, I had come to California because I was very interested in the entertainment business and figured that Mattel would at least get me closer to that and allow me to do what I knew best: brand marketing. So, for me, this was a perfect opportunity. That said, it was pretty risky to put our money where our mouth was.Joe Morrison: It was risky, yes, but the way we structured the deal it was less risky. We syndicated the show and for our "participation on the production," if you will, we received two-minutes a week of advertising for Mattel which we used for several of our other brands. The advertising that we got for our part of the deal on that thing was so undervaluedJohn Weems: There was a lot of concern about—between the show itself and the spots we were running—with critics asking: is this just an advertisement for the toy line? We eventually had Peggy Charren and Action for Children's Television lobbying against us. It's ruining our children's minds! Nevertheless, these concerns didn't stop the show from launching (or succeeding).Joe Morrison: The TV ratings went through the roof. Absolutely through the roof. All these kids went nuts over it. It was a phenomenon. It changed kids television.John Weems: You have to remember that before this, syndicated television was just re-runs of older shows. You know, like The Flintstones and The Jetsons. So even though we started off in a not ideal time-slot, by the end of the first week it was the #1 children's show in syndication because it was brand new. It was up against Fred Flintstone here! That was a really big deal. And of course, that success was also fueled by the fact that Filmation had made a great cartoon show.Joe Morrison: It really hit a chord.John Weems: And everybody knows what to do with a hit. About a week in, they were already moving the show to the prime time slot after school. And within about three months, Group W [a part of Westinghouse] extended deals with the stations from two years to four. I gotta give them credit for that. They knew we got the hottest thing going so we gotta go right now...Joe Morrison: Sales on the He-Man product line were going through the roof and thank god they did. Because other than He-Man, the company was going through a really tough time. Our Electronics Department [Mattel's videogame division] was going down the tubes, so we were hoisting everything on our shoulders. If not for He-Man, Mattel might have gone under. There's no question about it. No question. He-Man was doing, at that time, $400 million—if you took that piece out of the equation, there would be no Mattel. So it was kind of, you know, us against the world. It was a good time. It was a good time.Tim Kilpin: At the time I joined Mattel, the Masters business was bigger than Barbie. And so the scale of everything changed dramatically. My first job on the brand entailed writing package copy, writing a few of those mini-comics (that came with the action figure. Then I moved from packaging into the marketing group, where we worked very closely with the animation company. Scheimer's people. Making sure that the stories told on TV matched up with what we were doing with the toy line. Because back then, there was a lot of noise in the system about what's driving what. Are the toys driving the TV show, or is the TV show driving the toys? And the truth is that line was always blurred because we were trying to make them both work, and try to make them work together.John Weems: As you can imagine, Filmation did not want to be seen to be making a show that was somehow just a big giant ad for a toy line. They wanted to make what they considered to be a great show. So anything that resembled what they would term us as "giving creative suggestions," they were very resistant to it. I mean, they never came out and said, we will not take your suggestions." But, you know, they'd just shine us on.Tim Kilpin: How would I describe the relationship between Mattel and Filmation? Collaboration with tension, I guess, is the best way to put it. We, on the toy side, we owned the intellectual property and believed that it was driving the brand. And so from a marketing standpoint, we would work very closely with Product Development people to come up with a line plan and a story plan to anchor where we were going to do in 1985, '86, '87, etc. So we were creating characters, you know? We were creating the evil horde and the snake men and everybody else.Joe Morrison: I'm sure there may have been some ups and downs, but overall it was not a very difficult relationship. Filmation did good work and we always had that relationship—we had that trust—with Lou. They brought a lot to the table

Nevertheless, these concerns didn't stop the show from launching (or succeeding).Joe Morrison: The TV ratings went through the roof. Absolutely through the roof. All these kids went nuts over it. It was a phenomenon. It changed kids television.John Weems: You have to remember that before this, syndicated television was just re-runs of older shows. You know, like The Flintstones and The Jetsons. So even though we started off in a not ideal time-slot, by the end of the first week it was the #1 children's show in syndication because it was brand new. It was up against Fred Flintstone here! That was a really big deal. And of course, that success was also fueled by the fact that Filmation had made a great cartoon show.Joe Morrison: It really hit a chord.John Weems: And everybody knows what to do with a hit. About a week in, they were already moving the show to the prime time slot after school. And within about three months, Group W [a part of Westinghouse] extended deals with the stations from two years to four. I gotta give them credit for that. They knew we got the hottest thing going so we gotta go right now...Joe Morrison: Sales on the He-Man product line were going through the roof and thank god they did. Because other than He-Man, the company was going through a really tough time. Our Electronics Department [Mattel's videogame division] was going down the tubes, so we were hoisting everything on our shoulders. If not for He-Man, Mattel might have gone under. There's no question about it. No question. He-Man was doing, at that time, $400 million—if you took that piece out of the equation, there would be no Mattel. So it was kind of, you know, us against the world. It was a good time. It was a good time.Tim Kilpin: At the time I joined Mattel, the Masters business was bigger than Barbie. And so the scale of everything changed dramatically. My first job on the brand entailed writing package copy, writing a few of those mini-comics (that came with the action figure. Then I moved from packaging into the marketing group, where we worked very closely with the animation company. Scheimer's people. Making sure that the stories told on TV matched up with what we were doing with the toy line. Because back then, there was a lot of noise in the system about what's driving what. Are the toys driving the TV show, or is the TV show driving the toys? And the truth is that line was always blurred because we were trying to make them both work, and try to make them work together.John Weems: As you can imagine, Filmation did not want to be seen to be making a show that was somehow just a big giant ad for a toy line. They wanted to make what they considered to be a great show. So anything that resembled what they would term us as "giving creative suggestions," they were very resistant to it. I mean, they never came out and said, we will not take your suggestions." But, you know, they'd just shine us on.Tim Kilpin: How would I describe the relationship between Mattel and Filmation? Collaboration with tension, I guess, is the best way to put it. We, on the toy side, we owned the intellectual property and believed that it was driving the brand. And so from a marketing standpoint, we would work very closely with Product Development people to come up with a line plan and a story plan to anchor where we were going to do in 1985, '86, '87, etc. So we were creating characters, you know? We were creating the evil horde and the snake men and everybody else.Joe Morrison: I'm sure there may have been some ups and downs, but overall it was not a very difficult relationship. Filmation did good work and we always had that relationship—we had that trust—with Lou. They brought a lot to the table Tim Kilpin: For example, Orko as a character was created for the show. We never anticipated Orko as a toy, it was never a part of the process. But then as the show took off and got really popular, Orko became a really important character in the storytelling. And then we came back and made the toy. So it was a blurry line and sometimes, of course, there would be tension. Like, for example, we'd say we want to have Battle Bones in this episode. Because we wanted to sell more Battle Bones! And they'd say, "No, that doesn't make sense from a story standpoint." So we kind of had to learn each other's business a little bit. So we could understand why something did or didn't make sense. And it was a great learning experience because there was no rulebook for it. We were kind of just figuring it all out as we went.Tom Kalinske: The writing was terribly important. Creating the stories was very, very important. Because without it, you didn't have this world. You didn't have this environment that the boys could play in.Tim Kilpin: So we had that dialogue with Filmation every day. And we'd have our own debates internally too. Because we'd have our Entertainment tell us, "You can't just turn this into a parade of characters, trying to trot them out to the toy line."John Weeks: It had to sort of be its own organic universe.Tim Kilpin: Because otherwise kids would see through it. And so we had to learn from a toy marketing perspective what it meant to build a brand with a story behind it. Because the longer-term goal—for everybody—was always to build something that could last. We didn't want to just create a one-year or a two-year thing. Like most toys in this business. Let's not shoot ourselves in the foot here. Let's try to build it in a way so that it has the chance to live for multiple years. Let's build something, all of us together, that really has the chance to last. Now, we weren't necessarily successful on that front...

Tim Kilpin: For example, Orko as a character was created for the show. We never anticipated Orko as a toy, it was never a part of the process. But then as the show took off and got really popular, Orko became a really important character in the storytelling. And then we came back and made the toy. So it was a blurry line and sometimes, of course, there would be tension. Like, for example, we'd say we want to have Battle Bones in this episode. Because we wanted to sell more Battle Bones! And they'd say, "No, that doesn't make sense from a story standpoint." So we kind of had to learn each other's business a little bit. So we could understand why something did or didn't make sense. And it was a great learning experience because there was no rulebook for it. We were kind of just figuring it all out as we went.Tom Kalinske: The writing was terribly important. Creating the stories was very, very important. Because without it, you didn't have this world. You didn't have this environment that the boys could play in.Tim Kilpin: So we had that dialogue with Filmation every day. And we'd have our own debates internally too. Because we'd have our Entertainment tell us, "You can't just turn this into a parade of characters, trying to trot them out to the toy line."John Weeks: It had to sort of be its own organic universe.Tim Kilpin: Because otherwise kids would see through it. And so we had to learn from a toy marketing perspective what it meant to build a brand with a story behind it. Because the longer-term goal—for everybody—was always to build something that could last. We didn't want to just create a one-year or a two-year thing. Like most toys in this business. Let's not shoot ourselves in the foot here. Let's try to build it in a way so that it has the chance to live for multiple years. Let's build something, all of us together, that really has the chance to last. Now, we weren't necessarily successful on that front... Part 2: King Kandy and The Man Who Must Break YouJohn Weems: From a very early stage, we were of course talking about and thinking about the idea of a movie. You know, looking back it seems so odd. Because now it feels as though every movie is based on some kind of Marvel character. But back then, there was a resistance on the part of the studios. The feeling was that this is just a cheese ball toy line for kids. This would never work.Tom Kalinske: It was the same sort of thing that we'd been told when we first had the idea of doing a TV show.Joe Morrison: So we had started to look at different things and then Ed Pressman was introduced to us. Ed had always done really independent things as a producer [ranging from things like Das Boot to Conan the Barbarian]. Some very successful films. So he was an interesting guy. And his brother ran a company called Pressman Toys, which was one of the biggest gaming companies back then. So Ed came down to talk to us and he said, "Let me go shop this." And so eventually we let him do that.Gary Goddard: I don't remember how I heard about it, but somehow I had heard that Ed Pressman was looking for a director for Masters of the Universe. So I called him up, introduced myself and told him about some of the things I'd worked on.Tom Kalinske: Gary had done all sorts of different things. Never directed before, not a movie at least, but I believe he was responsible for one of those big, live shows over at Universal Studios. Conan The Barbarian, if I'm not mistaken.Gary Goddard: Yup, I was hired by Universal Studios to do their Conan show. I think I was 25 at the time and had been at Imagineering before that. I was there—as an Imagineer at Disney—at a very unique window in time. Working with all of the original guys that designed Disneyland and then Disney World. But there were only about 24 people in show design, of which me and two other guys were the under-30 guys. "The Kids," as we were called by the others. That was a great job. We basically designed all of the attractions, content and shows for all of the EPCOT and WORLD SHOWCASE attractions. There were draftsmen and architects and the MAPO team, but at the core 24 guys did all the creative work. We also worked on the beginnings of Tokyo Disney, as well as new attractions for Disneyworld and Disneyland. Like I said, it was a great job But a couple years after I had left Disney, I got this call from Peter Alexander at Universal. He called and said he was planning this CONAN attraction—he said Rolly Crump at Imagineering had recommended me—and he had heard that I was the guy. So I went over and met with him and we—me and my new company, Gary Goddard Productions—wound up creating the show, conceptualizing it, writing the script, directing it, producing it everything and that was a very cool show. I don't know if you've ever seen it, but it was pretty groundbreaking.Tom Kalinske: So he had a lot of expertise in that space, but he also had experiences in the toy industry as well.

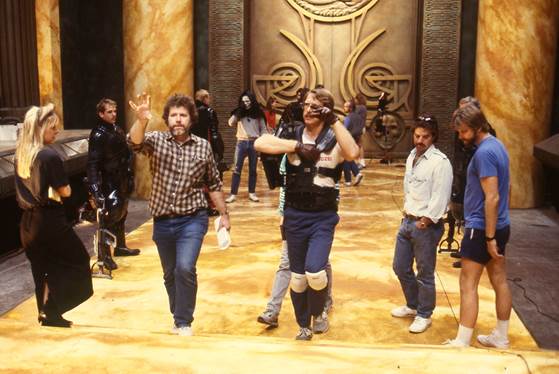

Part 2: King Kandy and The Man Who Must Break YouJohn Weems: From a very early stage, we were of course talking about and thinking about the idea of a movie. You know, looking back it seems so odd. Because now it feels as though every movie is based on some kind of Marvel character. But back then, there was a resistance on the part of the studios. The feeling was that this is just a cheese ball toy line for kids. This would never work.Tom Kalinske: It was the same sort of thing that we'd been told when we first had the idea of doing a TV show.Joe Morrison: So we had started to look at different things and then Ed Pressman was introduced to us. Ed had always done really independent things as a producer [ranging from things like Das Boot to Conan the Barbarian]. Some very successful films. So he was an interesting guy. And his brother ran a company called Pressman Toys, which was one of the biggest gaming companies back then. So Ed came down to talk to us and he said, "Let me go shop this." And so eventually we let him do that.Gary Goddard: I don't remember how I heard about it, but somehow I had heard that Ed Pressman was looking for a director for Masters of the Universe. So I called him up, introduced myself and told him about some of the things I'd worked on.Tom Kalinske: Gary had done all sorts of different things. Never directed before, not a movie at least, but I believe he was responsible for one of those big, live shows over at Universal Studios. Conan The Barbarian, if I'm not mistaken.Gary Goddard: Yup, I was hired by Universal Studios to do their Conan show. I think I was 25 at the time and had been at Imagineering before that. I was there—as an Imagineer at Disney—at a very unique window in time. Working with all of the original guys that designed Disneyland and then Disney World. But there were only about 24 people in show design, of which me and two other guys were the under-30 guys. "The Kids," as we were called by the others. That was a great job. We basically designed all of the attractions, content and shows for all of the EPCOT and WORLD SHOWCASE attractions. There were draftsmen and architects and the MAPO team, but at the core 24 guys did all the creative work. We also worked on the beginnings of Tokyo Disney, as well as new attractions for Disneyworld and Disneyland. Like I said, it was a great job But a couple years after I had left Disney, I got this call from Peter Alexander at Universal. He called and said he was planning this CONAN attraction—he said Rolly Crump at Imagineering had recommended me—and he had heard that I was the guy. So I went over and met with him and we—me and my new company, Gary Goddard Productions—wound up creating the show, conceptualizing it, writing the script, directing it, producing it everything and that was a very cool show. I don't know if you've ever seen it, but it was pretty groundbreaking.Tom Kalinske: So he had a lot of expertise in that space, but he also had experiences in the toy industry as well. Gary Goddard: One little known thing about me is that I created the Candyland characters for the Candyland board game for Milton Bradley. [laughing a bit to himself] Yup, yup, I'm King Kandy. When you play that, I'm King Kandy. And Tony Christopher [his business partner at the time] is Lord Licorice. And Rebecca Mills—who was our character designer—that's Princess Lolli. Every single character there was designed after one of the people that was working for my little company at the time.Goddard had founded his company—Gary Goddard Productions—in 1980. From a small office complex on Sunset Boulevard, his group offered a versatile set of experience; from hospitality design to live entertainment. Gary Goddard: Back in 1982, I think, Mattel was looking for creative consultants so they brought us to help with a project that we had created. They were going to do a gigantic toy line that promoted reading called The Peanut Butter Papers. Sadly the Chairman who had initiated that project passed away the following year, and our project entered a twilight zone and nothing ever happened with that. But it led to us consulting on other things.Joe Morrison: I had done a lot of work with Gary. Over the years, he had presented Mattel a bunch of different ideas that were quite good.Gary Goddard: Meanwhile, as I had mentioned earlier, I knew that Ed Pressman was looking for a director so I called him up and told him that I'd directed the Conan show. And so he went with David Odell [who had written a script for Masters of the Universe] to see the Conan show and then called me back and said, "Okay, we get it. Let's meet." So we met. I read the script and he goes, "I'm a big believer in first time directors and I think you can do this. But I have to be honest: Mattel needs to approve the director. They have approval rights. So I can't guarantee anything." And I looked at him and said, "I don't think you're going to have a problem with that." He was, of course, a little surprised by this, but I knew that Mattel knew I understood their brands and their characters.Joe Morrison: I felt that Gary could do a good job on it. So we gave him, you know, our endorsement.Tim Kilpin: Joe was good friends with Gary Goddard. So Gary was a known entity to the guys at Mattel. So it had as much to do with Gary's background as it did the sense that Mattel knew and could trust Gary.John Weems: There was a trust level there. We had a lot of faith in Gary.

Gary Goddard: One little known thing about me is that I created the Candyland characters for the Candyland board game for Milton Bradley. [laughing a bit to himself] Yup, yup, I'm King Kandy. When you play that, I'm King Kandy. And Tony Christopher [his business partner at the time] is Lord Licorice. And Rebecca Mills—who was our character designer—that's Princess Lolli. Every single character there was designed after one of the people that was working for my little company at the time.Goddard had founded his company—Gary Goddard Productions—in 1980. From a small office complex on Sunset Boulevard, his group offered a versatile set of experience; from hospitality design to live entertainment. Gary Goddard: Back in 1982, I think, Mattel was looking for creative consultants so they brought us to help with a project that we had created. They were going to do a gigantic toy line that promoted reading called The Peanut Butter Papers. Sadly the Chairman who had initiated that project passed away the following year, and our project entered a twilight zone and nothing ever happened with that. But it led to us consulting on other things.Joe Morrison: I had done a lot of work with Gary. Over the years, he had presented Mattel a bunch of different ideas that were quite good.Gary Goddard: Meanwhile, as I had mentioned earlier, I knew that Ed Pressman was looking for a director so I called him up and told him that I'd directed the Conan show. And so he went with David Odell [who had written a script for Masters of the Universe] to see the Conan show and then called me back and said, "Okay, we get it. Let's meet." So we met. I read the script and he goes, "I'm a big believer in first time directors and I think you can do this. But I have to be honest: Mattel needs to approve the director. They have approval rights. So I can't guarantee anything." And I looked at him and said, "I don't think you're going to have a problem with that." He was, of course, a little surprised by this, but I knew that Mattel knew I understood their brands and their characters.Joe Morrison: I felt that Gary could do a good job on it. So we gave him, you know, our endorsement.Tim Kilpin: Joe was good friends with Gary Goddard. So Gary was a known entity to the guys at Mattel. So it had as much to do with Gary's background as it did the sense that Mattel knew and could trust Gary.John Weems: There was a trust level there. We had a lot of faith in Gary. Gary Goddard: Mattel had two approvals on the movie. The director and the actor playing He-Man. And they'd already approved Dolph Lundgren, so he was part of the package when I signed on.Joe Morrison: The decision to go with Dolph came from when they were doing the financing and figuring out how much they could pay and what they could do. He was, I think, a reasonably price alternative.John Weems: And Dolph Lundrgren was hot after Rocky.Gary Goddard: He was a big, big...I wouldn't say "star," but he was a big celebrity because of his turn in Rocky. And he was selected because he looked like He-ManJohn Weems: Exactly like He-Man! So I think everybody knew he looked great...but could he act?Gary Goddard: After I became director, Ed Pressman set up a meeting with Dolph. At his house, I think. It was fine, it was a first meeting. Dolph's very personable, he has a great face—I knew that he was gonna photograph well—but then he started talking and in my mind I was thinking: uh-oh. As he was speaking, I was thinking: wow, we're gonna have some issue with him speaking with lines. Because his English...remember, in Rocky he only says one line: "I must break you."

Gary Goddard: Mattel had two approvals on the movie. The director and the actor playing He-Man. And they'd already approved Dolph Lundgren, so he was part of the package when I signed on.Joe Morrison: The decision to go with Dolph came from when they were doing the financing and figuring out how much they could pay and what they could do. He was, I think, a reasonably price alternative.John Weems: And Dolph Lundrgren was hot after Rocky.Gary Goddard: He was a big, big...I wouldn't say "star," but he was a big celebrity because of his turn in Rocky. And he was selected because he looked like He-ManJohn Weems: Exactly like He-Man! So I think everybody knew he looked great...but could he act?Gary Goddard: After I became director, Ed Pressman set up a meeting with Dolph. At his house, I think. It was fine, it was a first meeting. Dolph's very personable, he has a great face—I knew that he was gonna photograph well—but then he started talking and in my mind I was thinking: uh-oh. As he was speaking, I was thinking: wow, we're gonna have some issue with him speaking with lines. Because his English...remember, in Rocky he only says one line: "I must break you." Lillian Glass: I first worked with Dolph on Rocky IV. He had a very thick Swedish accent, so we worked on kind of Americanizing his accent to get him more roles in Hollywood. And he did great. He was a phenomenal person and a phenomenal client. Dolph is just an awesome human being.Gary Goddard: Look, Dolph worked hard. He had a great work ethic. He put in the hours. He had an acting coach, a dialogue coach and all that stuff. But my one frustration was that he was so new to everything, coming off of Rocky, and he looked at Stallone—as a director, writer, actor, everything—and he really emulated him, I think.Lillian Glass: From the very first moment that Dolph walked into my office, you could just tell that he had "it." He had something special. And the reason I know that is by working with so many people who did have it. I worked with Dustin Hoffman for Tootsie; I taught him how to sound like a woman. I worked with Sean Connery, Marlee Matlin—I taught her how to speak for the Academy Awards—and I just worked with Caitlin Jenner, teaching her how to be more feminine in her communications. The list goes on and on. And working with so many superstars and talented people in so many fields—you know, I've worked with actors, politicians, athletes—and you really know after working with all these winners who's got "it" and who doesn't.Gary Goddard: Dolph did a credible job. And he worked hard. But I don't think it's any secret that I did go to producer and I did try to get them to let me use another actor to dub him. But they felt that they were already paying all this money for Dolph Lundgren so they wanted Dolph Lundgren. Anyway, Ed was happy because he now had his approved director and he could now go make his movie. So Ed went to Warner Bros. and they said they would make it, but only at $15 million and Cannon said they would do it at $17.5 million. So he went with them. And...uh...the saga began.

Lillian Glass: I first worked with Dolph on Rocky IV. He had a very thick Swedish accent, so we worked on kind of Americanizing his accent to get him more roles in Hollywood. And he did great. He was a phenomenal person and a phenomenal client. Dolph is just an awesome human being.Gary Goddard: Look, Dolph worked hard. He had a great work ethic. He put in the hours. He had an acting coach, a dialogue coach and all that stuff. But my one frustration was that he was so new to everything, coming off of Rocky, and he looked at Stallone—as a director, writer, actor, everything—and he really emulated him, I think.Lillian Glass: From the very first moment that Dolph walked into my office, you could just tell that he had "it." He had something special. And the reason I know that is by working with so many people who did have it. I worked with Dustin Hoffman for Tootsie; I taught him how to sound like a woman. I worked with Sean Connery, Marlee Matlin—I taught her how to speak for the Academy Awards—and I just worked with Caitlin Jenner, teaching her how to be more feminine in her communications. The list goes on and on. And working with so many superstars and talented people in so many fields—you know, I've worked with actors, politicians, athletes—and you really know after working with all these winners who's got "it" and who doesn't.Gary Goddard: Dolph did a credible job. And he worked hard. But I don't think it's any secret that I did go to producer and I did try to get them to let me use another actor to dub him. But they felt that they were already paying all this money for Dolph Lundgren so they wanted Dolph Lundgren. Anyway, Ed was happy because he now had his approved director and he could now go make his movie. So Ed went to Warner Bros. and they said they would make it, but only at $15 million and Cannon said they would do it at $17.5 million. So he went with them. And...uh...the saga began. Part 3: A Midsummer Night's Mash-UpGary Goddard: I should start by saying that Ed Pressman and David Odell already had a finished screenplay, so the decision was already made—in order to make it for a low-budget—to have the story take place on earth. [As opposed to He-Man's home planet of Eternia, where the toy line and TV series took place]. So Julie [played by Courtney Cox] and Kevin [played by Robert Duncan McNeill] were already in it. This was an established thing. The movie started, in the original screenplay, literally on earth, with a very beat-up, bedraggled He-Man pounding on the back door of Julie's house and her finding this guy who's a strange heroic warrior. This was a fish-out of water story...set on Earth.Tim Kilpin: At the time, I remember feeling like this could really be bad. This could really not work. How do you set it on earth and also make it seem relevant to kids and teens and blah, blah-blah, blah-blah-blah. But remember, this was before Transformers and GI Joe, so nobody had a great frame of reference for movies like this.

Part 3: A Midsummer Night's Mash-UpGary Goddard: I should start by saying that Ed Pressman and David Odell already had a finished screenplay, so the decision was already made—in order to make it for a low-budget—to have the story take place on earth. [As opposed to He-Man's home planet of Eternia, where the toy line and TV series took place]. So Julie [played by Courtney Cox] and Kevin [played by Robert Duncan McNeill] were already in it. This was an established thing. The movie started, in the original screenplay, literally on earth, with a very beat-up, bedraggled He-Man pounding on the back door of Julie's house and her finding this guy who's a strange heroic warrior. This was a fish-out of water story...set on Earth.Tim Kilpin: At the time, I remember feeling like this could really be bad. This could really not work. How do you set it on earth and also make it seem relevant to kids and teens and blah, blah-blah, blah-blah-blah. But remember, this was before Transformers and GI Joe, so nobody had a great frame of reference for movies like this. Gary Goddard: I argued heavily that we should bookend with Eternia. So I said: what if we open on the throne room and we close on the throne room and that way it won't feel like a budget contrivance. It'll feel like it's meant to be because this is the place where everything's happening. So much later, I contrived everything—the rise of the moon, the planets aligning, the transformation into a god, all that stuff, so that it would happen right there in the throne room. We open in the throne room and we close in the throne room so that's how I got the budget to build one massive set that had a lot of production value because I said I'm gonna use it for the opening 20 minutes and the closing 20 minutes.Tim Kilpin: Those were probably the best parts of the movie.The other reason those scenes worked so well was because they put Frank Langella and his considerable talents on full display.

Gary Goddard: I argued heavily that we should bookend with Eternia. So I said: what if we open on the throne room and we close on the throne room and that way it won't feel like a budget contrivance. It'll feel like it's meant to be because this is the place where everything's happening. So much later, I contrived everything—the rise of the moon, the planets aligning, the transformation into a god, all that stuff, so that it would happen right there in the throne room. We open in the throne room and we close in the throne room so that's how I got the budget to build one massive set that had a lot of production value because I said I'm gonna use it for the opening 20 minutes and the closing 20 minutes.Tim Kilpin: Those were probably the best parts of the movie.The other reason those scenes worked so well was because they put Frank Langella and his considerable talents on full display.  Gary Goddard: I think my biggest task was trying to get the right team together. I had seen Frank in the Broadway production of Amadeus and I never forgot it. He was an actor who cold basically act through the makeup, act through the mask, and I realized that Dolph, with the speech issues, probably wasn't the guy to center the film on. So I centered the film on Skeletor. All without telling anyone. I had to give a spine, an anchor to the movie. And then I found Meg, who was a perfect foil because she's fantastic too. So the real moments of power and real emotion are when Frank and Meg are on the screen and then the humor comes a little bit from Kevin and Julie, but really from Griwldor. He was a replacement for Orko. Because we couldn't do Orko. Because we would have had to do Orko with a guy hanging on wires, flying around. It wouldn't have worked. So we made the decision, it was a conscious decision, you gotta understand, Orko and Battlecat—who we would have needed to do with stop-motion animation—Orko and Battlecat still existed, somewhere back on Eternia, but I made the conscious decision to not saddle myself with those things. Because I think a film is only as good as its weakest element, it's Achilles heel. And I just knew that an Orko charcter hanging on wires, it would have been a nightmare. So what I wanted to do was pick the characters that I thought could be adapted well.One of those characters was Teela, He-Man's right hand lady.

Gary Goddard: I think my biggest task was trying to get the right team together. I had seen Frank in the Broadway production of Amadeus and I never forgot it. He was an actor who cold basically act through the makeup, act through the mask, and I realized that Dolph, with the speech issues, probably wasn't the guy to center the film on. So I centered the film on Skeletor. All without telling anyone. I had to give a spine, an anchor to the movie. And then I found Meg, who was a perfect foil because she's fantastic too. So the real moments of power and real emotion are when Frank and Meg are on the screen and then the humor comes a little bit from Kevin and Julie, but really from Griwldor. He was a replacement for Orko. Because we couldn't do Orko. Because we would have had to do Orko with a guy hanging on wires, flying around. It wouldn't have worked. So we made the decision, it was a conscious decision, you gotta understand, Orko and Battlecat—who we would have needed to do with stop-motion animation—Orko and Battlecat still existed, somewhere back on Eternia, but I made the conscious decision to not saddle myself with those things. Because I think a film is only as good as its weakest element, it's Achilles heel. And I just knew that an Orko charcter hanging on wires, it would have been a nightmare. So what I wanted to do was pick the characters that I thought could be adapted well.One of those characters was Teela, He-Man's right hand lady.  Chelsea Field: I actually met Gary Goddard a few years before Masters of the Universe. He was doing a show called Conan the Barbarian up at Universal so I went up there and auditioned for him. At the time, I was so desperate. I had just moved back to LA—I was living with my mom, running out of money—and I remember Gary asking, "Can you do any tumbling?" And I thought to myself: no, I haven't tumbled since I was 12. But I said, "Um, sure!" And he goes, So I threw an aerial, which I hadn't thrown in like 8 years, and then he goes, "Okay, can you do a back handspring?" So again I say "Um, sure!" Then I threw a back handspring and my arms started to collapse. Somehow I got my feet underneath me. I swear, the fact I didn't break my neck, I'm a so lucky. But that just sort of goes to show you that when you want a job, you will do anything. Thank god he didn't ask if I could do a backflip.Gary Goddard: Chelsea had auditioned for me at Universal, for the Conan show. And I remembered her because she was a striking beauty. She was very, very beautiful—a beautiful body—very physical, great face. I must have seen a hundred different women for Teela and what I wanted to know was could they act and could they hold a sword? Could they hold a blaster and not look out of place? And by the way, we had no time, there was no time for training on this film. This was a Cannon film.

Chelsea Field: I actually met Gary Goddard a few years before Masters of the Universe. He was doing a show called Conan the Barbarian up at Universal so I went up there and auditioned for him. At the time, I was so desperate. I had just moved back to LA—I was living with my mom, running out of money—and I remember Gary asking, "Can you do any tumbling?" And I thought to myself: no, I haven't tumbled since I was 12. But I said, "Um, sure!" And he goes, So I threw an aerial, which I hadn't thrown in like 8 years, and then he goes, "Okay, can you do a back handspring?" So again I say "Um, sure!" Then I threw a back handspring and my arms started to collapse. Somehow I got my feet underneath me. I swear, the fact I didn't break my neck, I'm a so lucky. But that just sort of goes to show you that when you want a job, you will do anything. Thank god he didn't ask if I could do a backflip.Gary Goddard: Chelsea had auditioned for me at Universal, for the Conan show. And I remembered her because she was a striking beauty. She was very, very beautiful—a beautiful body—very physical, great face. I must have seen a hundred different women for Teela and what I wanted to know was could they act and could they hold a sword? Could they hold a blaster and not look out of place? And by the way, we had no time, there was no time for training on this film. This was a Cannon film. Cannon had a reputation for making less-than quality films. And during this time especially they'd started to run into some financial troubles. Gary Goddard: So we were struggling to find a Teela and then I remembered Chelsea. I had no idea where she was, but I mentioned her to Vicky Thomas—our casting director—that Chelsea had been a dancer and I had this feeling. So Vicky tracked her down and brought her in and I had to put her through several auditions because she had never been a lead before and everyone was like "are you sure are you sure?"Chelsea Field: I wound up doing probably ten auditions for the thing. Gary kept calling me back. And at the time, I didn't really know why. I just felt like they weren't sure and I had to keep working to get this job. But I look back now and I realize: oh, I hadn't done anything! And he was probably trying to convince the producers that I could do it!Gary Goddard: "Are you sure?" "Are you sure?" "Are you sure?"Chelsea Field: So I'd go back there for my 3rd call, my 4th call, my 5th call and every time I'd be jumping around the couches and over chairs and behind the coffee table and every time I did I'd be going [making laser noises] "Peow! Peow!" because I had a laser gun. And I felt like an idiot. I felt like I was jumping around like I was a five-year-old boy.Gary Goddard: She was just great though.Chelsea Field: Then finally, one day, my agents called and they said "are you sitting down?" and I said "no," and I was standing and I can remember exactly where I was standing—I was looking out the window—and they said, "You got Masters of the Universe." And I screamed so loud, there was like an explosion out of my chest. Like I'd scored a touchdown on the final play to win the Super Bowl. Because you have to remember that, back then, going from being a professional dancer into acting was so, so difficult. The perception was that dancers made terrible actors. So getting the part, it was a huge deal for me. I truly have never felt that kind of explosion of joy since then and I just know that feeling will never be repeated.Chelsea Field wasn't the only young actress getting her first chance at a leading role. The other was Courtney Cox.

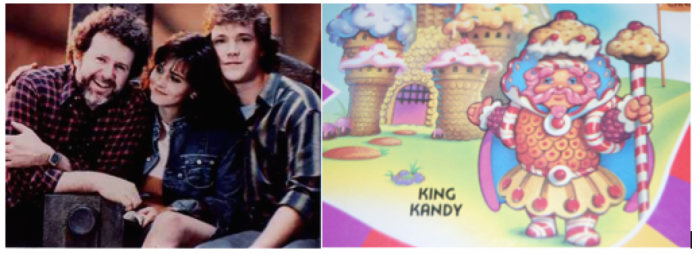

Cannon had a reputation for making less-than quality films. And during this time especially they'd started to run into some financial troubles. Gary Goddard: So we were struggling to find a Teela and then I remembered Chelsea. I had no idea where she was, but I mentioned her to Vicky Thomas—our casting director—that Chelsea had been a dancer and I had this feeling. So Vicky tracked her down and brought her in and I had to put her through several auditions because she had never been a lead before and everyone was like "are you sure are you sure?"Chelsea Field: I wound up doing probably ten auditions for the thing. Gary kept calling me back. And at the time, I didn't really know why. I just felt like they weren't sure and I had to keep working to get this job. But I look back now and I realize: oh, I hadn't done anything! And he was probably trying to convince the producers that I could do it!Gary Goddard: "Are you sure?" "Are you sure?" "Are you sure?"Chelsea Field: So I'd go back there for my 3rd call, my 4th call, my 5th call and every time I'd be jumping around the couches and over chairs and behind the coffee table and every time I did I'd be going [making laser noises] "Peow! Peow!" because I had a laser gun. And I felt like an idiot. I felt like I was jumping around like I was a five-year-old boy.Gary Goddard: She was just great though.Chelsea Field: Then finally, one day, my agents called and they said "are you sitting down?" and I said "no," and I was standing and I can remember exactly where I was standing—I was looking out the window—and they said, "You got Masters of the Universe." And I screamed so loud, there was like an explosion out of my chest. Like I'd scored a touchdown on the final play to win the Super Bowl. Because you have to remember that, back then, going from being a professional dancer into acting was so, so difficult. The perception was that dancers made terrible actors. So getting the part, it was a huge deal for me. I truly have never felt that kind of explosion of joy since then and I just know that feeling will never be repeated.Chelsea Field wasn't the only young actress getting her first chance at a leading role. The other was Courtney Cox.  John Weems: I think Gary was the one who wanted Courtney Cox, which turned out to be a pretty prescient decision. Give Gary credit for that. She had just done the Springsteen video and he liked her look and all of that.Gary Goddard: I wanted a very fresh new face with a, you know, pretty but in a wholesome kind of suburban way. And the funny story on that one was that when she came in she was all made-up, as actresses tend to do, and the casting director Vicky Thomas brought her in and said, "I think you're really gonna like her." At the time, she was quote "the girl from the Bruce Springsteen video." Okay, good. So she comes in, I met her and she was very nice. But when she left, because with the makeup on, she looked like she was 25, I was like "Vicky, I don't think so. She's really nice and she read well, but I don't think she's in." Vicky said, "let me have her come in tomorrow and I'll have her come in without any makeup." Cause Vicky was pretty sure that she was the right one. And that next day, she was fantastic. And afterwards I said to Vicky, "you're right. That was her." So Vicky gets the accolades for the smarts on that one.

John Weems: I think Gary was the one who wanted Courtney Cox, which turned out to be a pretty prescient decision. Give Gary credit for that. She had just done the Springsteen video and he liked her look and all of that.Gary Goddard: I wanted a very fresh new face with a, you know, pretty but in a wholesome kind of suburban way. And the funny story on that one was that when she came in she was all made-up, as actresses tend to do, and the casting director Vicky Thomas brought her in and said, "I think you're really gonna like her." At the time, she was quote "the girl from the Bruce Springsteen video." Okay, good. So she comes in, I met her and she was very nice. But when she left, because with the makeup on, she looked like she was 25, I was like "Vicky, I don't think so. She's really nice and she read well, but I don't think she's in." Vicky said, "let me have her come in tomorrow and I'll have her come in without any makeup." Cause Vicky was pretty sure that she was the right one. And that next day, she was fantastic. And afterwards I said to Vicky, "you're right. That was her." So Vicky gets the accolades for the smarts on that one. Like most movies, some parts in this film were harder to cast than others. But, unlike most films, this movie had a uniquely unusual problem with some of its parts. Gary Goddard: A lot of the toy characters couldn't be adapted well. I mean, I adapted Beast Man and, man, I took crap for that too because "he doesn't look like the toy." Well, it's not a toy! It's a fucking movie now. And so I created characters of my own that worked for this story. Characters who I thought could live and breathe on the screen. Like Karg [played by Robert Towers] and Saurod [played by Pons Maar] and Blade [played by Anthony De Longis].Anthony De Longis: I was coming off one of my favorite roles—playing this assassin, Piedre, who was a master of disguise on MacGyver—and I had been recommended to Gary as both an actor and as a superior swordsman. I don't really remember too much about my first meeting with Gary, except that I vaguely recall him telling me that I'd have to shave my head, or be in makeup for hours, in order to play the character. I made my choice and they bought me an eclectic razor, which I used in rush hour traffic to and from our 6 weeks on location in Whittier.William Stout: Anthony was amazing. He played Blade, but he was also the stunt coordinator for all the sword-fighting scenes and he also doubled as Skeletor too.Anthony De Longis: Part of my job entailed training Dolph how to wield his sword. We met and I very quickly convinced him that I knew what I was doing and that I was there to help him look great. I'm in the Black Belt Hall of Fame, the Martial Arts Hall of Fame and the Knife-Throwing Hall of Fame, so I try to bring that element of truth while telling a story and creating an illusion. Dolph took to the training really well, no surprise. But we did not get much time to rehearse. A lot of the choreography was done virtually on the spot. And it's a great tribute to Dolph's talent as an athlete and martial artist that he was able to roll with the punches and get the job done with style. What we assembled was literally done on the day of the shoot.William Stout: Anthony was really good at staging the fights so that they looked dramatic. And I tried to design a set that took advantage of the fact that we were going to have sword fights. I went back and watched all the Errol Flynn swashbucklers, which were designed by one of my great heroes, his name was Anton Grot. And I looked at how Grot how designed the sets, and so I made sure that there were steps and places to hide behind and columns and ups and downs, so it gave the actors a lot to work with.Anthony De Longis: Those sets that Bill designed were great for what we needed to do. Especially because He-Man's sword-—which I used to call "Buick Slayer" because it was rather ponderous and hazardous, shall we say—was very tough to maneuver. Anybody with less strength and athleticism than Dolph would not have been able to manipulate it with such apparent ease. Dolph did a really good job and I was very proud of our work together.

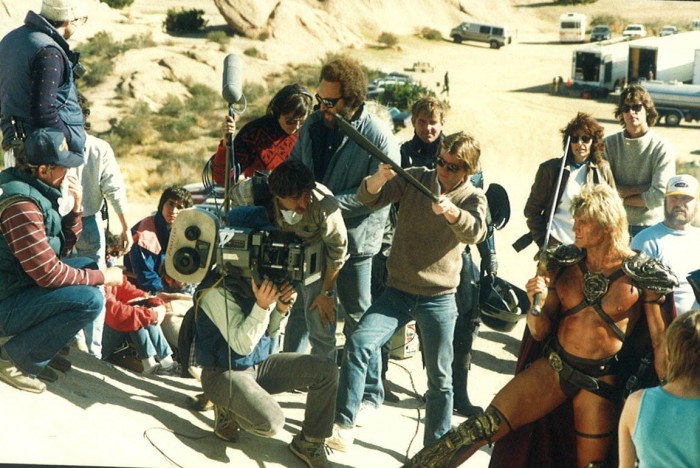

Like most movies, some parts in this film were harder to cast than others. But, unlike most films, this movie had a uniquely unusual problem with some of its parts. Gary Goddard: A lot of the toy characters couldn't be adapted well. I mean, I adapted Beast Man and, man, I took crap for that too because "he doesn't look like the toy." Well, it's not a toy! It's a fucking movie now. And so I created characters of my own that worked for this story. Characters who I thought could live and breathe on the screen. Like Karg [played by Robert Towers] and Saurod [played by Pons Maar] and Blade [played by Anthony De Longis].Anthony De Longis: I was coming off one of my favorite roles—playing this assassin, Piedre, who was a master of disguise on MacGyver—and I had been recommended to Gary as both an actor and as a superior swordsman. I don't really remember too much about my first meeting with Gary, except that I vaguely recall him telling me that I'd have to shave my head, or be in makeup for hours, in order to play the character. I made my choice and they bought me an eclectic razor, which I used in rush hour traffic to and from our 6 weeks on location in Whittier.William Stout: Anthony was amazing. He played Blade, but he was also the stunt coordinator for all the sword-fighting scenes and he also doubled as Skeletor too.Anthony De Longis: Part of my job entailed training Dolph how to wield his sword. We met and I very quickly convinced him that I knew what I was doing and that I was there to help him look great. I'm in the Black Belt Hall of Fame, the Martial Arts Hall of Fame and the Knife-Throwing Hall of Fame, so I try to bring that element of truth while telling a story and creating an illusion. Dolph took to the training really well, no surprise. But we did not get much time to rehearse. A lot of the choreography was done virtually on the spot. And it's a great tribute to Dolph's talent as an athlete and martial artist that he was able to roll with the punches and get the job done with style. What we assembled was literally done on the day of the shoot.William Stout: Anthony was really good at staging the fights so that they looked dramatic. And I tried to design a set that took advantage of the fact that we were going to have sword fights. I went back and watched all the Errol Flynn swashbucklers, which were designed by one of my great heroes, his name was Anton Grot. And I looked at how Grot how designed the sets, and so I made sure that there were steps and places to hide behind and columns and ups and downs, so it gave the actors a lot to work with.Anthony De Longis: Those sets that Bill designed were great for what we needed to do. Especially because He-Man's sword-—which I used to call "Buick Slayer" because it was rather ponderous and hazardous, shall we say—was very tough to maneuver. Anybody with less strength and athleticism than Dolph would not have been able to manipulate it with such apparent ease. Dolph did a really good job and I was very proud of our work together. William Stout: Boy, Dolph...there was a line of ladies. Just waiting to meet Dolph in his trailer. He was quite the ladies man. Incredibly beautiful human being. He's very large, but he's gorgeously proportioned. But I think of all the actors, he was the one I interacted with least. I figured that most of my work with Dolph was done once I finalized his costume.Anthony De Longis: My costume? It weighed 55 pounds at least! I was in surgical rubber from head to toe. And then I was in gloves. And then I had boots and I had chain mail. And my chain mail, I came to find out, was 10 six-foot lengths of pipe cut into quarter inch pieces. So I was wearing somewhere between 50-60 feet of steel pipe. So they'd throw that over my shoulders and then on top of that they had these shoulder pads with spikes. As soon as I saw that I said, "well, I guess I won't be doing any shoulder rolls with this." But, golly, Bill did a great job with everything, the production values look great.Gary Goddard: Originally, there had been a different production designer. Bill was there as a concept designer, but initially we had a different production designer that just didn't work out. We were in our fourth or fifth week ore pre-production and he just wasn't getting it. Very talented, but you get into the sci-fi fantasy and if someone doesn't feel it from the guts, it's hard for them to understand it. So he was doing these intellectual interpretations of things. I said, "You know, I don't think you're really getting this." And he said, "well I hate this fucking stuff."John Weems: Almost from the get-go, the tone of the film was a big concern. How do you make an action movie that, by definition, has to appeal to young males and still have something that is still true to the character—especially with He-Man being pretty goodie two shoes. So that was a big question mark. The tone.Gary Goddard: That was one of the reasons that I wanted to shoot the movie at night. If you try and imagine these characters—these creatures and monsters—walking around in broad daylight...I don't know. To me, there's no theatricality to that, there's no magic to that. The sunlight is very unforgiving, I think it would have made everything look very clunky. So I decided that everything [in the story] would happen in one night. And I think a theatrical lighting and creating more of a dream state helps that a lot.William Stout: Night shoots are tough. The only thing worse than a night shoot is a night shoot in the rain...it's no picnic. But the reason you do a night shoot is usually either for atmosphere or to cover up your budgetary limitations. And in our case it was to cover up budgetary limitations. Details that would give away what something really was, they just fall back into the shadows and you don't see them. It works great. Plus it's easier to see lasers and stuff like that at night in the dark.Gary Goddard: And during the night, all this magic—it's kind of like A Midsummer Night's Dream—all the magic happens from sunset to sunrise.

William Stout: Boy, Dolph...there was a line of ladies. Just waiting to meet Dolph in his trailer. He was quite the ladies man. Incredibly beautiful human being. He's very large, but he's gorgeously proportioned. But I think of all the actors, he was the one I interacted with least. I figured that most of my work with Dolph was done once I finalized his costume.Anthony De Longis: My costume? It weighed 55 pounds at least! I was in surgical rubber from head to toe. And then I was in gloves. And then I had boots and I had chain mail. And my chain mail, I came to find out, was 10 six-foot lengths of pipe cut into quarter inch pieces. So I was wearing somewhere between 50-60 feet of steel pipe. So they'd throw that over my shoulders and then on top of that they had these shoulder pads with spikes. As soon as I saw that I said, "well, I guess I won't be doing any shoulder rolls with this." But, golly, Bill did a great job with everything, the production values look great.Gary Goddard: Originally, there had been a different production designer. Bill was there as a concept designer, but initially we had a different production designer that just didn't work out. We were in our fourth or fifth week ore pre-production and he just wasn't getting it. Very talented, but you get into the sci-fi fantasy and if someone doesn't feel it from the guts, it's hard for them to understand it. So he was doing these intellectual interpretations of things. I said, "You know, I don't think you're really getting this." And he said, "well I hate this fucking stuff."John Weems: Almost from the get-go, the tone of the film was a big concern. How do you make an action movie that, by definition, has to appeal to young males and still have something that is still true to the character—especially with He-Man being pretty goodie two shoes. So that was a big question mark. The tone.Gary Goddard: That was one of the reasons that I wanted to shoot the movie at night. If you try and imagine these characters—these creatures and monsters—walking around in broad daylight...I don't know. To me, there's no theatricality to that, there's no magic to that. The sunlight is very unforgiving, I think it would have made everything look very clunky. So I decided that everything [in the story] would happen in one night. And I think a theatrical lighting and creating more of a dream state helps that a lot.William Stout: Night shoots are tough. The only thing worse than a night shoot is a night shoot in the rain...it's no picnic. But the reason you do a night shoot is usually either for atmosphere or to cover up your budgetary limitations. And in our case it was to cover up budgetary limitations. Details that would give away what something really was, they just fall back into the shadows and you don't see them. It works great. Plus it's easier to see lasers and stuff like that at night in the dark.Gary Goddard: And during the night, all this magic—it's kind of like A Midsummer Night's Dream—all the magic happens from sunset to sunrise. A Midsummer Night's Dream wasn't the only Shakespearean influence on Masters of the Universe. An appreciation for The Bard also helped shape Skeletor's role in the film. Gary Goddard: Why does Skeletor do what he does? Why is he a "bad guy?" He tells you. We gave you the line. "I must possess all or I possess nothing." It's the burning driving ambition. I must possess all. I mean, this is Shakespeare. What drives half of Shakespeare? A King's ambition. They will kill, maim, rape, do whatever they have to do, in order to either get power or maintain power. And what is it in the psyche? Skeletor to me was the physical representation of someone who's devoted his life to attaining power, whatever that means, in every way that is, and he will not be happy until he has it. And frankly, he won't be happy after he does have it. With Skeletor, Frank and I were having a great time because we'd find quotes from Shakespeare and quotes from Moliere and James Campbell. We looked for lines that would play out in a dramatic way and would work these into his dialogue. So we had fun in our own way.Tim Kilpin: But the thing you have to remember—if you go back to the early days, the formation of these characters—is that there was nothing so dramatic behind it. It wasn't a Shakespearian drama. It wasn't Tolkien-esque, with someone figuring out all the mythology in advance. It was kind of handmade at the beginning. And it was a little ad hoc in terms of the original mythology. I'm sure there are people who wouldn't want to hear that, but it was. And the show came along and helped us build dimension and depth. And then the movie came along and gave us an opportunity to do more of that. And some of these worked better than others, but it wasn't a grand plan at the outset. It was built as we went.John Weems: Long story short: I don't think any of us thought we had Gone With The Wind here.