Is 'Mulholland Drive' Really The Greatest Film Of The 21st Century? (Or How I Learned To Love David Lynch)

Until a few months ago, if the name David Lynch came up in film discussion, I would have inwardly shrugged. It had been years since I watched one of Lynch's films. It had also been years since Lynch had even made a new feature (the last one being Inland Empire in 2006). But after screening Blue Velvet, Lost Highway, and Mulholland Drive back in the day, I felt I had sampled enough of the director's work to know that I was not a fan. His films just never spoke to me. Individual moments lingered in memory, but if anything, I was only confounded and disturbed by those moments.

What to make of the closet scene from Blue Velvet? Or the party scene from Lost Highway? More than any semblance of plot, it was scenes like those that lingered in memory. If someone started talking about Lynch, I would immediately think of that moment when Frank Booth, played by Dennis Hopper, starts inhaling gas from an oxygen mask and moaning "Mommy" before sinking to his knees between a woman's legs. I believe they call that nightmare fuel.

Fast forward a decade or so. Last year, Mulholland Drive topped a BBC poll of the 100 greatest films of the 21st century. Over 175 film critics from around the world voted on this thing. Hearing it was unbelievable enough, but when I looked at the list, and saw it there in writing, I was only further confounded. What were these critics seeing that I was missing?

And this began my journey into the world of Mulholland Drive and David Lynch. A journey I'm glad I took (and one I recommend you take, too).

Converted to the Cult of Lynch

Mulholland Drive is a film that lends itself to different readings. The film presents a puzzle, and far be it from me or any dusty old theory to offer one pat solution. Again, everyone has the right to their own interpretation (not to mention their own opinion as to whether a movie like this is really worth pouring over in the first place). Yet, despite the film's outwardly confusing nature, this is one instance where Lynch the labyrinth designer did give us a roadmap for how to find our way out of —or rather, deeper into — his wondrous maze.

In my own (admittedly offbeat) head, I sort of equate Lynch with Remy the rat in the Pixar film Ratatouille. Some people might be inclined to say, "I smell a rat," when they bite into one of his specially prepared dishes. As I sit here in my own Anton Ego pose, my feelings on Lynch teeter between begrudging respect and full-blown adulation. Mulholland Drive is a film that I initially found confusing — until I realized what was maybe going on, and it took on a whole new weight.

Now I come away feeling like it really is the masterpiece all those critics make it out to be. Apologists love to trot out this line, but I think Mulholland Drive really is one of those instances where it is true that the genius of the film cannot always be appreciated on a first viewing. The dream theory (which we'll discuss below) is what gives this film such profound emotional heft for me. I think most people can probably relate, on some level, to how the idealized version of their life is often at odds with the terrible truth of reality.

The snarky answer to the question, "Is Mulholland Drive Really the Greatest Film of the 21st Century?" would be, "No, shamus, it's not." Personally, my pick for the 21st century's greatest film would probably still be No Country for Old Men, followed closely by another 2007 film, There Will Be Blood. Yet both those films ranked behind Mulholland Drive on the BBC's Top 10.

But with the question, "What year is it?" still ringing in my ears from the Twin Peaks finale, I'm tempted to say Mulholland Drive might actually crack my own top 10 now.

The Winkie’s Diner Scene

After hearing the effusive praise for the film and seeing it receive the top accolade on a list like that, the thing that finally sold me on giving Mulholland Drive another chance was the simple act of rewatching one scene from it on YouTube. That scene, which takes place at a diner called Winkie's on Sunset Blvd. in L.A., really functions as its own scary little short film. The way the scene is edited offers a masterclass in tension-building, and it has a complete, five-minute arc to it, so you can watch it and enjoy it for what it is without needing to know anything else about the rest of the movie. Not to hype it too much, but this might make a riveting entry point for anyone on the fence about giving Lynch their time.

For much of Mulholland Drive's running time, the diner scene would seem to be entirely disconnected from the main story. Lynch likes to tell surreal, sprawling stories with an ensemble cast, but there is a sense that his fondness for fresh faces and messy dream logic leads to a build-up of narrative dead-ends.

Though he made an Oscar-nominated film called The Straight Story (whose plot more or less lives up to the title), it has become obvious that Lynch isn't much interested in telling that kind of story. Often, he seems more interested in just striking a certain tone, conveying mood over clear meaning. In a way, some of his films are more like tone poems than straightforward narratives. That is all well and good, but sometimes it really does seem like this director has made it his mission to flout convention at the cost of coherence. Lynch fans can (and will) argue differently, or that this is the point of his work. But it's something that all audiences must grapple with when they first make the plunge.

Accordingly, it almost feels at first like the diner scene is just a stray vignette, some scene that Robert Altman deemed too horrifying and left on the cutting room floor when he was making Short Cuts. The face of "Dan," the guy doing most of the talking in the diner scene (mark the eyebrows; he's played by recognizable character actor Patrick Fischler) only pops up once later in a cameo. But the timing of that cameo is crucial.

Decoding David Lynch: Is it a Fool’s Errand?

I want to delve into one of the oldest, most prevalent theories about Mulholland Drive, but before we get into any spoilers, it might do to say a few general words about David Lynch and his resistance to being decoded. In a lot of ways, Lynch eschews explanation—not just with his art, but with the way he talks about his art (or remains cagey about it) in interviews. Speaking with BAFTA in London, Lynch once said:

"Believe it or not, Eraserhead is my most spiritual film."

"Elaborate on that," the interviewer said.

With a laugh, Lynch replied, "No, I won't."

Here it merits mention that the end of Lynch's recent television odyssey, Twin Peaks: The Return, seemed to reposition an entity named Judy, or Jowday, as the new mother of all evil behind everything in the series. But in Chinese, the word jiao dai can be translated as "to explain" or "make clear." As Peaks TV podcast co-host Joanna Robinson and Twitter user Rob Carmack have pointed out, this could be an in-joke meaning that the main antagonist of Twin Peaks the whole time was "the concept of explanation and clarity."

More than an Orpheus figure, the show's finale seemed to position its central hero, Agent Dale Cooper, as a Sisyphus figure, doomed to keep rolling the rock up the hill in the never-ending fight against evil. In the same way, maybe it is a Sisyphean task to try and decipher David Lynch's artistic intent with any of his work. Though he was barely lucid at the time, David Bowie's character in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me did once say, "We're not going to talk about Judy at all."

But now let's talk about Judy. Yeah, let's Judy this up with some ex post facto film analysis. Because in the context of Mulholland Drive, Lynch himself already freed us up to do that with an old insert he included in the DVD of the movie.

The list we are about to unpack is no big secret. You can find it on Wikipedia, so for fans hardcore and otherwise, it might be old news. But I share it here for the benefit of latecomers to the Lynch party, like me, who are only just now coming around to the director's work, perhaps discovering or rediscovering old films of his in conjunction with Twin Peaks. After the list, we will shift into spoiler territory, so even though Mulholland Drive may be laden with enough rich subtext to make it spoiler-proof, if you have not seen the film, you may want to bow out now and come back when you have.

“David Lynch’s 10 Clues to Unlocking This Thriller”

From here on out, this discussion will presume a basic knowledge of events in Mulholland Drive. Fire up the film projector now, and as you rewatch Mulholland Drive, keep in mind "David Lynch's 10 Clues to Unlocking This Thriller":

Breaking Down Mulholland Drive

People have often noted how Lynch's films have a dreamlike quality to them, and Mulholland Drive is suffused with that same quality. Yet here it is more than just window-dressing; it is actually integral to the plot of the film.

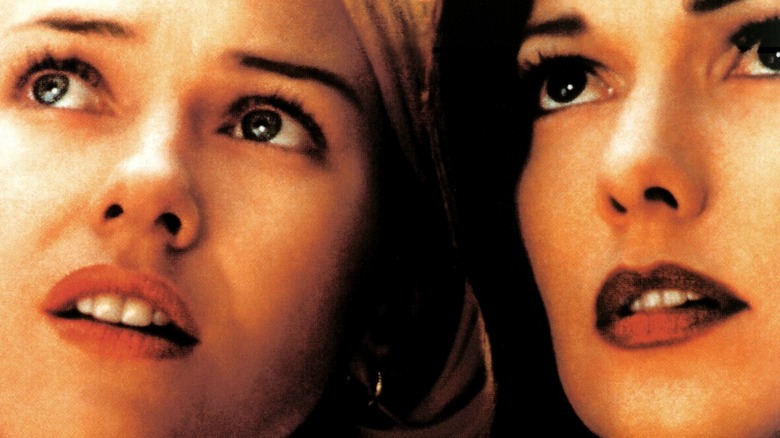

In a nutshell, according to one popular theory, the bulk of what we see in Mulholland Drive is a dream made up of reconstituted faces and other elements from the life of a failed actress named Diane Selwyn, who hired a hitman to kill her ex-lover, then was overcome by guilt and committed suicide. There is no one right interpretation for a film like this, of course, but littered throughout Mulholland Drive, there are enough signposts to support said theory that it, in retrospect, it seems readily apparent: this is what's happening in the film.

When he was interviewed at the Cannes Film Festival the year the film came out, Lynch himself reportedly insisted that Mulholland Drive does tell a coherent, comprehensible story. Casual movie-watchers might not have the patience to suss it out with a second viewing, but if you examine the film with the dream theory in mind, bolstered by Lynch's clues and some other supporting evidence, it actually makes perfect sense. By the standards of a nightmare or drug trip, there is nothing bizarre about it. It is actually somewhat tame. The movie merely plunges us into an illusory world, populated by frightening, soot-covered hobos (where have we seen those before?) and maniacal, miniaturized elderly couples. Not bizarre at all...

One of the hints before the credits that Lynch talked about in clue #1 would appear to be a hint about Diane's backstory as the smiling small-town girl who won a jitterbug dance contest before packing up her suitcases and jetting off to Hollywood. She was a big fish in a small pond till she got out to L.A., the city that swallows up dreamers. The other clue is especially pronounced, inasmuch as the last thing we see before the title of the film comes up is the hazy POV of someone in bed, their head hitting the pillow.

What follows next is a dream. While there is no conclusive evidence that I've been able to pick up on, we can infer from the general state of her life that Diane may have a drug problem. At one point in the dream, when leaving home for her audition, she says, "Don't drink all the coke!" It seems like a total non-sequitur. Would she really need to say that to her new house guest, Rita, another adult woman? Maybe this is just the way for her subconscious to sanitize her memories of how her apartment became a drug den for her and her lover. It's not a stretch to say that drinking coke could be a thin cipher for, you know, doing cocaine.

L.A. was one of the cities most affected by the American crack epidemic of the 1980s and 1990s. So there's also that to ponder. Or maybe there are no drugs involved, and Diane is just losing her mind like Norma Desmond, the character played by Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard. That is certainly a possibility, too, as Mulholland Drive is in many ways Lynch's answer to Sunset Boulevard, a classic that proved highly influential on him as a filmmaker.

At any rate, coming down from a high on some substance, Diane slips into a fugue state and forgets herself. Scenes in her dream take on an aspect of wish fulfillment; she imagines a vast web of conspiracy, furthered by mobsters and men in shadowy rooms, all for the aim of installing another actress as the lead in The Sylvia North Story. This is the title of the film (see clue #3) where Diane met her ex-lover, Camilla, in the real world. The actress who supplants Diane in the dream has the same face as the woman who supplants her as Camilla's lover in the real world.

But Diane wants to forget that. And she especially wants to forget that Camilla is now dead. In the dream, the hitman Diane hired (at Winkie's, as seen toward the end of the movie) is reimagined as an incompetent whose bumbling actions forestall the death of her ex-lover. In reality, the hitman has carried out his contract and returned the blue key of clue #5 to her apartment table as a sign that it is finished. Their meeting at the diner is also where Diane's subconscious latches onto the name "Betty" as a name for her dream self. She gets the name from her waitress's nametag. Through the looking glass, it's reversed and the waitress is wearing the name "Diane."

The location of the accident mentioned in clue #4 is the Hollywood Hills. Several times the camera fixates on the lights of Los Angeles, as seen from the hills. These lights have beckoned dreamers for decades.

The place where the accident happens is also the same stretch of winding road on Mulholland Drive where Diane met Camilla in the real world, accompanying her to a party where she had her heart broken; met a sympathetic face who would become the landlady in her dream; and randomly saw a stern face that would become one of the mobsters in her dream. She also sees a certain cowboy there, who promised one of her dream avatars, "You'll see me two more times if you do bad." And lo and behold, this is the second time we've seen him since then.

The man behind Winkie's, referenced in clue #9, is meant to portray the evil that festered from Diane's heartbroken jealousy. The funny thing is, this so-called "man," who is listed in the closing credits simply as "Bum," is actually played by an actress named Bonnie Aarons. (Most recently she played the demon nun in The Conjuring 2.) But it is this great evil, embodied by the bum's dirty visage, which shows up again at the end of the film, holding that same blue key, the hitman's marker. Effectively this is the key to Pandora's box. Note how Betty, the more innocent self, disappears, merging with her other amnesiac self, right before Rita uses the key to open the blue box in the dream. This box, with its black window into reality, opens up a world of hurt on Diane, unleashing the forces of guilt on her.

Guilt takes the form of the elderly couple, two figures from her past (which is not so innocent as she would like to remember). The old couple is never explicitly identified in the real world, but we see them by Diane's side in her memories of winning the jitterbug contest, and in the dream she renders them as the people she met on her flight into LAX. So it is clear she associates them with her innocence, pre-L.A. Their corny interactions with her at LAX are soon undercut by chilling smiles, a sense that something is wrong with this picture.

That is what is "felt, realized, and gathered at the Club Silencio" (per clue #7). Hollywood dreams and the innate human tendency for self-delusion have put a veil over Diane's eyes. Movie magic is a trick. "There is no band. This is all a tape recording. It is an illusion." Diane is slowly waking, once again, to reality; her brain has already begun peeling back the layer of artifice by showing us blonde wigs and collapsed stage performers with voices that continue to sing doomed love songs in Spanish. Rebekah Del Rio's a capella rendition of "Crying" plays like a funeral dirge for Diane. Rita, meanwhile, retains no memory of herself because she is not herself at all. She is a manifestation of Diane's subconscious, as are all the other characters in the dream, like Dan at the diner, and the hapless, cuckolded Adam.

All roads (or in this case, conspiratorial calls) lead back to Diane and the red lampshade by her phone. Clue #2 points to a woman in denial, dreaming, refusing to answer the phone because she is unable to consciously come to terms with the murder she orchestrated in the real world. The real Rita, a.k.a. Camilla, was cruel and commanding, a happy heartbreaker who appears to have slept her way to the top (see clue #8). As a ladder to fame and privilege, she is marrying Adam, the director of The Sylvia North Story, but at the same party where he announces their engagement, she is clearly seen kissing another woman.

After the Club Silencio scene, the film shifts from a fugue state, overlaid with a peppy Old Hollywood sheen, to grief-stricken reality. "The robe, the ashtray, and the coffee cup" of clue #6 are all background details that can be used to track the real-world timeline. The ashtray, for instance, is retrieved by Diane's ex-roommate (likely a lover she met on the rebound from Camilla), but there it is again, a moment later, indicating we have moved backward in time.

In answer to the question of, "Where is Aunt Ruth?" in clue #10...well, Aunt Ruth is dead. Dead, and divested of her Hollywood fortune. At the party, Diane flat-out says that she inherited some money when her "aunt died." In the dream, Aunt Ruth is "working on a movie that's being made in Canada," but the joke in the trade used to be that an actor consigned to Canada was as good as dead. Diane soon joins Aunt Ruth in the afterlife with a self-inflicted gunshot to the head. No more tiny tormentors to guilt-trip her.

Last but not least, if Lynch's clues were not enough, the dialogue itself is seeded with many hints, which only further compound the convincing case that Diane is dreaming for most of the film. "I just came here from Deep River, Ontario," she says in her guise as Betty, "and now I'm in this ... dream place." Pause for effect. "Dream place." Later, when pursuing the mystery of her new houseguest's identity, she urges Rita, "C'mon. It'll be just like in the movies. We'll pretend to be someone else." Furthermore, the words she says as she picks up the phone to dial Diane Selwyn, her unknown self, are, "It's strange to be calling yourself."