'Halloween' At 40: How John Carpenter's Original Film Frames Itself As A Violent Coming-Of-Age Movie

On October 25, 1978, John Carpenter's Halloween, the original Golden Age slasher movie and greatest of them all, hit theaters. It's been four full decades now since audiences met Michael Myers, whose reign of masked terror has spanned eleven films. The most recent sequel, also titled Halloween, is the best-reviewed installment in the franchise since 1978 and last weekend, it broke the box office record for slasher movie openings.

Part of what makes Carpenter's original so great and keeps us talking about it forty years later — even in academic circles, where it's been analyzed in much depth — is that it's not just simple sadism for genre fiends. The Library of Congress doesn't usually select those kinds of flicks for the National Film Registry. Halloween, conversely, was inducted in 2006. Subsequent outings in the long-running, albeit poorly received film series it spawned (not to mention many off-brand imitators) have replicated the teen slasher formula. Too often, perhaps, they muted the subtext of Carpenter's foundational genre film.

If Halloween were a literary work, you might call it a bloody Bildungsroman, one whose traumatic coming-of-age centers on a girl named Laurie Strode, played by Jamie Lee Curtis. This is a movie with some meat to it, so unearth your knives from the kitchen drawer and let's incise John Carpenter's Halloween on its 40th anniversary.

As unsettling as it is, the POV prologue to Carpenter's Halloween — in which the camera takes on the perspective of the young Michael Myers as he stalks and stabs his elder sister, Judith — is something of a red herring. Seeing Michael unmasked at the end as a child actor with '70s hair almost ruins it, as if putting such a face on the Reaper robs him of his mystique.

This isn't really Myers' story, any more than Jaws is the great white shark's story. Neither does the story belong to Dr. Sam Loomis (Donald Pleasance), even though it's his character who is introduced in the next scene, on a rainy night fifteen years later when Myers escapes the sanitarium where he is being held.

Dr. Loomis doesn't always sound like the best psychiatrist, at least not when he's referring to his patient as "it" or "the evil." His purest function, it would seem, is to characterize the threat that the real protagonist of this film will face.

Halloween is Laurie Strode's story. It's about her forced awareness of death and desire, twin realities that signal the loss of innocence and onset of experience in a person's life. Myers and his murder victims give form to these concepts. Of the two, death comes crashing in harder ... yet without Laurie to anchor the narrative, all the bloodshed would mean nothing.

We see Myers set his sights on Laurie back in Haddonfield, Illinois, outside his abandoned childhood home. The way the camera lingers over his shoulder as he watches her from behind, moving down the sidewalk, is all the more chilling when you consider what this slasher icon represents in his original incarnation.

The Grim Specter of Fate

There's a crucial scene in Halloween that comes about fifteen minutes into the movie. In it, Laurie is sitting at the back of a classroom, daydreaming, while the voice of her off-screen English teacher drones on matter-of-factly. At one point, the teacher's voice even recedes to the background as Carpenter's classic piano-and-synth score kicks in (the music is still bewitching and really carries this movie far). However, everything the teacher is saying is very important.

The teacher is talking about the end of a book by an author named Samuels, but her discussion of the novel's themes might just as well be a statement of thematic purpose from the movie itself. She says:

"What Samuels is really talking about here is fate. You see, fate caught up with several lives here. No matter what course of actions Collins took, he was destined to his own fate. His own day of reckoning with himself. The idea is that destiny is a very real, concrete thing that every person has to deal with."

At this point, Laurie looks out the window and sees her new stalker, Michael Myers, staring at her from across the street in his unchanging, expressionless white mask.

The teacher promptly lassos Laurie back into the lesson, asking her how Samuels' view of fate is different from that of another writer named Costain. In her answer, Laurie proceeds to disentangle the notion of fate from the limited purview of religion, saying that Samuels viewed fate as "a natural element like earth, air, fire and water." The teacher states:

"That's right. Samuels definitely personified fate. In Samuels' writing, fate is immovable. Like a mountain. It stands where man passes away. Fate never changes."

This last line transitions directly into the scene that first introduces the idea of the "boogeyman" into the movie. It's the one where Tommy Doyle, the kid Laurie babysits, is being taunted by a trio of older boys, school bullies. "He's gonna get you!" the boys chant. "The boogeyman is coming!"

The movie clearly conflates Michael Myers with the idea of fate as an inescapable force. Yet fate is a general term ... how should we define it here?

If you take it to mean that our lives are pre-ordained, the truth of that is debatable even within the confines of movie talk. Terminator 2: Judgment Day, for instance, holds that famous movie line: "There's no fate but what we make for our ourselves."

On the other hand, if fate in Carpenter's Halloween can be understood to mean death, then the truth of that is inarguable. Sooner or later, everybody dies. That fate, as it were, catches up with all of us. There's no avoiding it.

Seen from this perspective, Michael Myers takes his place in a long line of vivid cinematic representations of the Grim Reaper, like the unrelenting assassin, Anton Chigurh, in No Country for Old Men—another great film with mortality on its mind. Released in 2007, No Country is a fairly recent movie example, but on celluloid, you could trace the tradition of quietus-as-a-character back at least half a century earlier. Look no further the hooded, chess-playing figure of Death in Ingmar Bergman's 1957 masterpiece The Seventh Seal.

If there were ever any doubt — beyond the body count he racks up — that Death at its most elemental and unstoppable is what Michael Myers represents, Dr. Loomis surely puts that to rest when he says to a local lawman in Haddonfield, "Death has come to your little town, Sheriff!" Suddenly it no longer seems so strange to hear Loomis refer to Myers as an "it."

Throughout much of Halloween's running time, Myers cuts through suburbia like a phantom. In one scene, he even drapes a white sheet over himself like a ghost. This makes it all the more appropriate that the movie should be set on Halloween night, since the roots of the holiday and its trick-or-treating practice lay not in crass commercialism — candy and costumes — but in the concept of ghosts returning to their earthly abodes. Hence the movie's tagline: "The Night He Came Home!"

In Haddonfield, Myers is always there, tailing the teenagers in his station wagon, or lurking on the edge of the film frame, face unseen. He even stalks Tommy, though the kid is oblivious as he walks home from school and Myers ultimately drives off, perhaps because Tommy's too young and not yet ready to confront death.

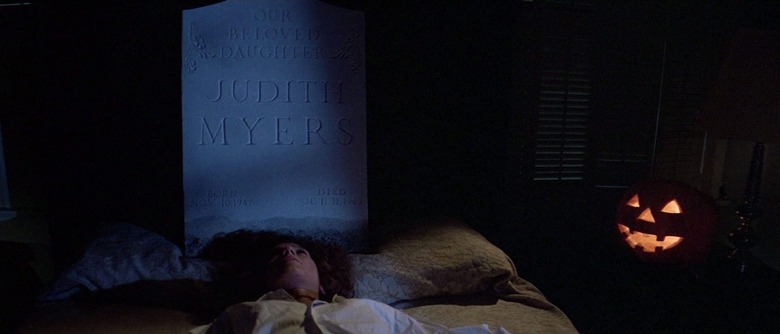

His time will come, but when it does, he'll be played by Paul Rudd in a mid-'90s sequel with a 6% Tomatometer rating. In the meantime, there's Laurie, who is right on the cusp of adulthood. The movie plunges her into a suburban nightmare, which has its most surreal moment when Laurie discovers one of her friends in bed with her throat sliced and the tombstone for Judith Myers positioned over her head.

From the nightstand, a glowing jack-o-lantern leers at the body. More bodies soon come popping out of other spots in the darkened room, and it's as if Laurie is lost in a funhouse hall of mirrors, with the Reaper's handiwork being reflected back at her at every turn.

Ignorance and Survival

Though its choice of late-night monster movie homages did predict Carpenter's remake of The Thing, Halloween helped establish certain conventions of the slasher genre, so it lacks the meta knowingness of a film like Wes Craven's Scream. In that film, a scene from Halloween served as a conversation piece at a house party, where the group's resident genre expert enumerated a short list of rules for how to survive a horror movie. One of those rules involved the line, "I'll be right back," which a doomed teenager actually utters in Halloween.

Laurie Strode has played mother to a legion of "final girls," but despite her scream queen cred, she doesn't always act smart in Halloween. Indeed, by today's seen-it-all standards, Laurie does appear guilty of making stupid mistakes, simply because there were decades worth of genre road yet to be traveled and she didn't have the same well-plotted slasher roadmap that the post-modern movie brats of Scream did.

Toward the end of the movie, she's all too quick to drop her only defensive weapon, a kitchen knife, and let down her guard with a homicidal maniac lying temporarily immobilized on the floor behind her. This happens not once, but twice during her final showdown in the house with Michael Myers.

It's the kind of thing that initially makes a viewer want to talk back to the screen, yelling, "No! What are you doing? Get out of there!" Upon further reflection, however, it's rather fitting, insofar as Laurie is human and human beings survive sometimes because of their ability to forget. Laurie cheats death, but if its certitude were present at the forefront of her mind at all times, she might be locked in existential terror, unable to breathe or move or live.

Death isn't the only unconscious force at play during her swift rite of passage into adulthood. It's a subtler thread in Halloween, but Laurie is also grappling with her sense of self amid social pressures in relation to the opposite sex.

Where Desire Meets Death

The conventional wisdom with slasher films is that the final girl is saved because she's a virgin. After all the other promiscuous teenagers have died, the final girl lives by virtue of her chastity. For all their sex and violence — the kills that genre fans love to rank — it's been argued that slasher movies actually harbor a puritanical streak, with their barely concealed conservative viewpoint bleeding through every time a teen unclothes, only to meet a grisly end.

As Scream puts it, "Sex equals death." More recently, the film It Follows remixed this erotophobia into the new high concept of a sexually transmitted supernatural stalker.

Certainly, Michael Myers, the crazed killer, could be said to have issues with the sight of amorous teenagers. Yet attributing the punishment he metes out to some kind of overarching disapproval and retribution on the part of Halloween, the movie itself, might be a mistake, one that offers a superficial take on Carpenter's multi-layered film.

Carpenter himself has resisted such a moralizing interpretation. In a widely disseminated quote, he's painted Laurie less as a chaste virgin and more as an uptight girl who "doesn't have a boyfriend" and is "sexually frustrated." In his words, "all that sexually repressed energy starts coming out" of Laurie in the form of phallic knives and knitting needles, which she uses to stab Myers, her twisted surrogate of a boyfriend, as he doggedly pursues her.

Art has a way of taking on a life of its own, heedless of its creators' intentions. Having said that, Carpenter's thoughts get to the core of what makes Halloween a deeper movie and different one, thematically, than the one people talk about when they imply it's a cautionary tale, censuring its characters for pre-marital sex.

Since the main action in Halloween unfolds over a single calendar date, October 31, what we glean of Laurie's identity comes mostly through dialogue and the interactions she has with her friends, Lynda and Annie. As they are leaving school that day, Lynda, the blonde cheerleader, remarks on all the books Laurie is carrying, how she practically needs a shopping cart to get them home.

"As usual," Laurie says, "I have nothing to do." To which Lynda retorts: "It's your own fault, and I don't feel a bit sorry for you."

Laurie is stuck babysitting that night, but her friends seem to regard this as a matter of choice on her part, as if she's resigned to being the anti-social one in the group. Annie blithely comments that Laurie "never goes out," even hinting that she "scares away" guys.

Though its first sequel would fall into the early '80s habit of retconning franchise characters as brother and sister (see also: Return of the Jedi), the original Halloween does flirt with the idea of Michael Myers, Death himself, being something of a warped suitor for Laurie. This happens when Annie pulls ahead of Laurie on the sidewalk to check out the row of bushes where Laurie has just seen Myers playing peek-a-boo with her.

Annie chimes, "Laurie, dear, he wants to talk to you. He wants to take you out tonight!"

It's not that Laurie's a saint, although as they're smoking pot in the car later, Annie does tell her, "I always said you'd make a fabulous girl scout." It's more that Laurie appears to be going through an awkward teen phase where's she's still uncomfortable in her own skin.

In the car, Laurie asks Annie what she's going to wear to the school dance the next night, and Annie says, "I didn't know you thought about things like that, Laurie." Annie talks about Laurie getting herself a date, and when Laurie lets slip the name of a boy she'd like to go with, Annie seizes on this as a telling admission, exclaiming, "I knew it! So you do think about things like that, huh, Laurie?"

The desire is there; Laurie's just buried it within herself, so much so that even when Annie manages to set Laurie up with the boy she likes, Laurie tries to back out of it on the phone. Before the night is over, however, she will find herself on a collision course with Michael Myers. Unlike desire, death cannot be denied.

It's interesting to note the slight clothing transformation that Laurie undergoes as the movie progresses. When we first meet her, she looks more like a modestly dressed schoolgirl, with tights and a turtleneck covering up any loose patches on her body where skin might show. Toward the end of the movie, as her confrontation with Myers draws nearer, we see that she's unbuttoned her collar, rolled up her sleeves, and assumed a more mature, self-possessed, womanly look. Even her hair looks different.

Halloween is a movie about a girl undergoing a violent awakening, casting off the last vestiges of innocence as she's assaulted with a terrible truth and suddenly grows up overnight in the worst way imaginable. In that respect, the film can perhaps be viewed as a close cousin to its contemporary Carrie, the 1976 Brian DePalma adaptation of Stephen King's novel about a high schooler whose latent telekinetic powers awaken as she hits puberty.

The difference here is that Carrie carried the monster within herself, whereas Laurie Strode meets it as a symbolic external force. In Halloween, Laurie's burgeoning realization takes shape as the Shape, the mask worn by Michael Myers, who appears like a ghost outside Laurie's window with her clean, white, clotheslined bedsheets flapping around him in the wind. She can't elude this boogeyman.

The movie ends with Laurie crying, followed by the disembodied sound of Myers' mask-breathing as the camera shows the interior and exterior of Haddonfield's murder houses. They look like any other houses. Maybe that's the point.

Michael Myers could be anywhere. In a sense, he's everywhere. He's the unseen driver who glides hypnotically parallel to you, tracing your sidewalk steps. He's the home invader who appears under the front porch light. He's the shadow that crosses the wall while two young lovers are in bed.

Death has penetrated the civilized safety of the suburbs. It looms over the rows of houses, ready to come calling when you least expect it.