How Did This Get Made: Gabriel Hardman, From Mr. Magoo To Mr. Christopher Nolan

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

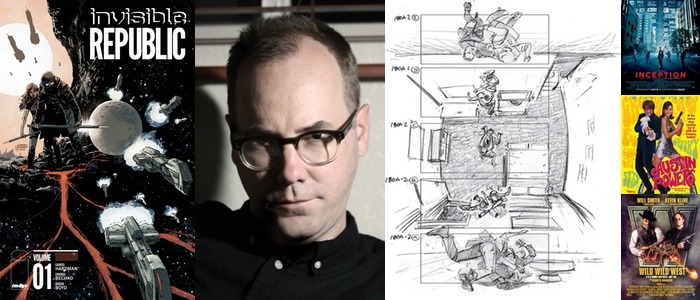

In 1993, at only 19 years old, an aspiring comic book artist named Gabriel Hardman got what appeared to be a big break: the chance to pencil Marvel's War Machine. But not long after completing the assignment, Hardman chose to ditch comics, move to Hollywood and try to make it as a storyboard artist.

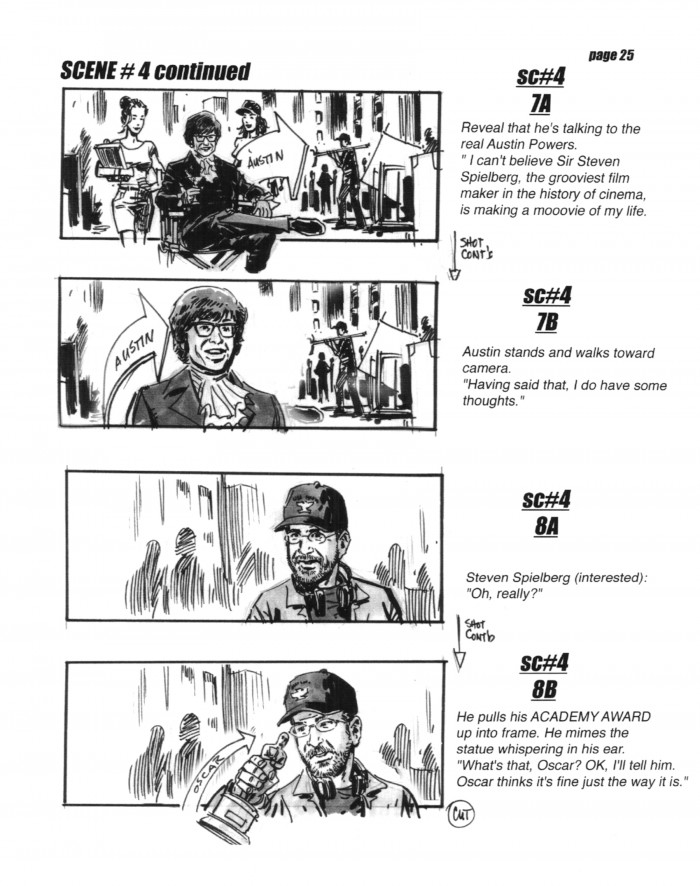

By any measure of success, there's no doubt that Hardman "made it." Over the next two decades, he worked on a variety of beloved and/or critically acclaimed projects; ranging from Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (1997) to Interstellar (2014). But at the same time, while on that upward trajectory, he storyboarded a handful famous flops. Including three films which have been the focus of How Did This Get Made? episodes: Wild Wild West, Spider-Man 3 and Green Lantern.

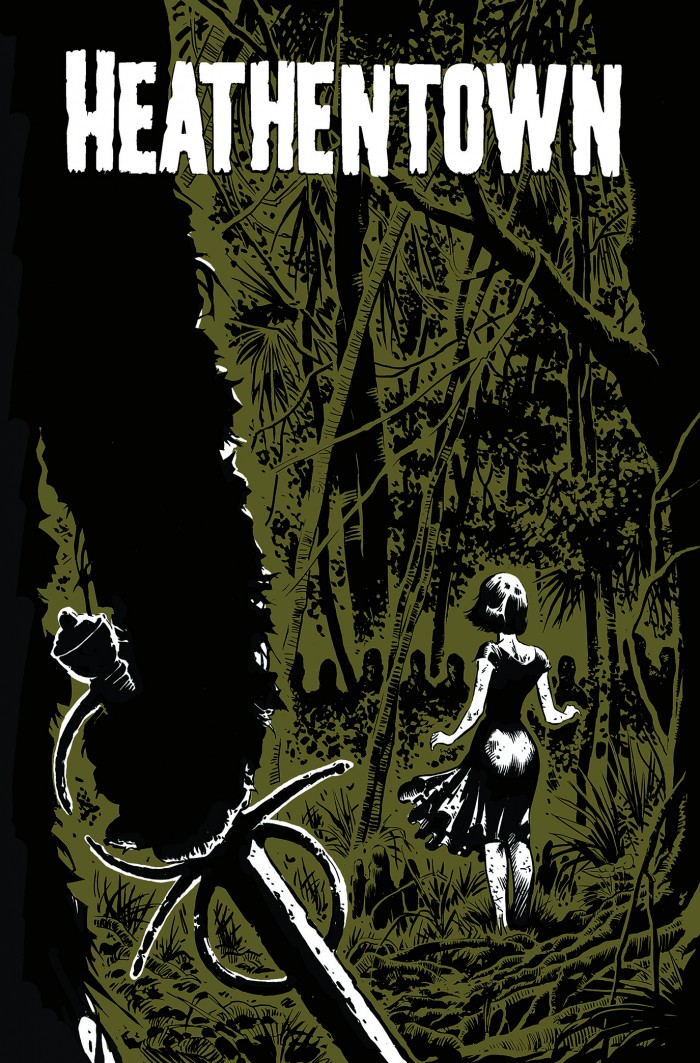

Interestingly enough, it took a frustrating experience on one of those three films to lead Hardman back to the career he had previously left. And, since then, he has regularly toggled between working in comics (such as Invisible Republic and Heathentown) and working on films (such as Inception and The Dark Knight Rises). To learn more about this unexpected journey, we spoke with Gabriel Hardman about some of the ups and downs in his career.

Gabriel Hardman Interview: From Mr. Magoo to Mr. Christopher Nolan

How Did This Get Made is a companion to the podcast How Did This Get Made with Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael which focuses on movies. This regular feature is written by Blake J. Harris, who you might know as the writer of the book Console Wars, soon to be a motion picture produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg. You can listen to the new edition of the HDTGM podcast here.

For eBook week, HarperCollins has kindle version of Console Wars on sale for just $1.99. So if anybody had an interest in reading the book, this is a good week to get it.

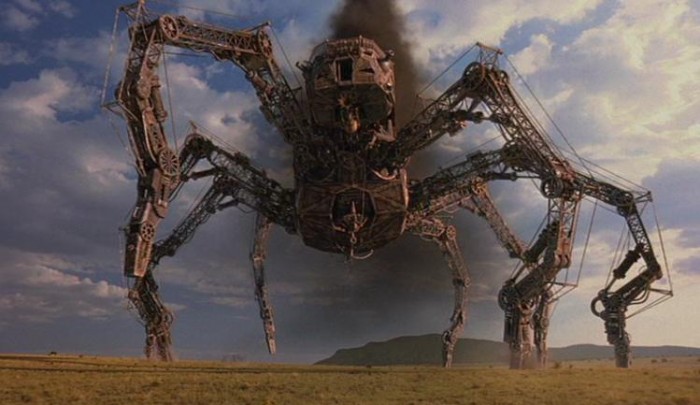

Part 1: How Did These Get Made?

Blake Harris: Although most of this conversation will focus on movies that you have worked on, let's start off by talking about one that you didn't work on: Kazaam.Gabriel Hardman: Right, so I didn't actually work on Kazaam. Early in my career, before I'd ever worked on films, I had an agent who—unbeknownst to me—was telling people I interviewed with that I was the storyboard artist on Kazaam. In an attempt, you know, pad my resume.Blake Harris: That's quite the resume builder...Gabriel Hardman: Exactly, right? So anyway, a few months go by and I have this meeting with a production designer. He looks down at the resume my agent had sent him and says, "Wait, you didn't work on Kazaam." I had no idea what he was talking about. And so what ensued was basically the most uncomfortable conversation imaginable: not only am I being accused of lying, but I'm being called on the carpet for a movie like that.Blake Harris: That's hilarious. But while Kazaam wasn't a movie that you actually worked on, you have worked on a couple that Paul, Jason and June have tackled on the podcast. One of those was Wild Wild West. Can you tell me a bit about how you got that job and what the experience was like? Gabriel Hardman: I got hired by recommendation, that's usually how it works. On a personal level, I should mention that working on this movie got me a big raise and introduced me to a bunch of people that I'd work again with later on. So it was very good for me in that respect. I should also mention that, at the time, everybody involved was coming off Men In Black, so there was this assumption that Wild Wild West would be something really good.Blake Harris: So could you tell, as you were working on the film, that maybe this one wasn't going to turn out quite so great?Gabriel Hardman: Well, things like legless Kenneth Branagh were obviously not going to work. There were a lot of not-so-good elements to this. But, even so, you can't always tell how things are going to play until it all comes together. So I don't think it was clear how "eh" the movie was going to be until, really, I saw a full cut of the film. Until it was clear how the stuff wasn't playing. Because it's such a big, dopey mess—like with the giant mechanical spider, that sort of thing—but what I think really kills the movie is just how it doesn't play at all. How tepid all that stuff is. There's a world where that awful stuff could actually be funny, but you can't always tell when you're working on it.

Gabriel Hardman: I got hired by recommendation, that's usually how it works. On a personal level, I should mention that working on this movie got me a big raise and introduced me to a bunch of people that I'd work again with later on. So it was very good for me in that respect. I should also mention that, at the time, everybody involved was coming off Men In Black, so there was this assumption that Wild Wild West would be something really good.Blake Harris: So could you tell, as you were working on the film, that maybe this one wasn't going to turn out quite so great?Gabriel Hardman: Well, things like legless Kenneth Branagh were obviously not going to work. There were a lot of not-so-good elements to this. But, even so, you can't always tell how things are going to play until it all comes together. So I don't think it was clear how "eh" the movie was going to be until, really, I saw a full cut of the film. Until it was clear how the stuff wasn't playing. Because it's such a big, dopey mess—like with the giant mechanical spider, that sort of thing—but what I think really kills the movie is just how it doesn't play at all. How tepid all that stuff is. There's a world where that awful stuff could actually be funny, but you can't always tell when you're working on it. Blake Harris: I remember expecting Wild Wild West to be more like Maverick, but to your point it just fell flat. It lacked the same fun, adventure and excitement. But the point you make is very interesting because I suspect that gaging those qualities– fun, adventure and excitement—are probably very tough to determine during the process.Gabriel Hardman: It can be. Especially when you're not directly seeing how all these things connect. My biggest memory of Wild Wild West though was dealing with Barry Sonnenfeld, the director. You know, he had been the DP of the Coen Brothers' first couple of movies and then he went on to direct stuff. He wears a big cowboy hat and cowboy boots, but he's also a very neurotic guy. And my main memory was that I went to show him some boards right before they did the cast table read. At a Century City Hotel. And he's, like, trying to describe how the action in a scene will happen—a fight, with one guy on top of another—so he makes me lay down on the floor and he straddles me in front of everyone. It was humiliating.Blake Harris: That's a great first impression.Gabriel Hardman: Yeah, exactly. I mean, Barry is an eccentric character. I liked working with him though. I did the second Men in Black as well.

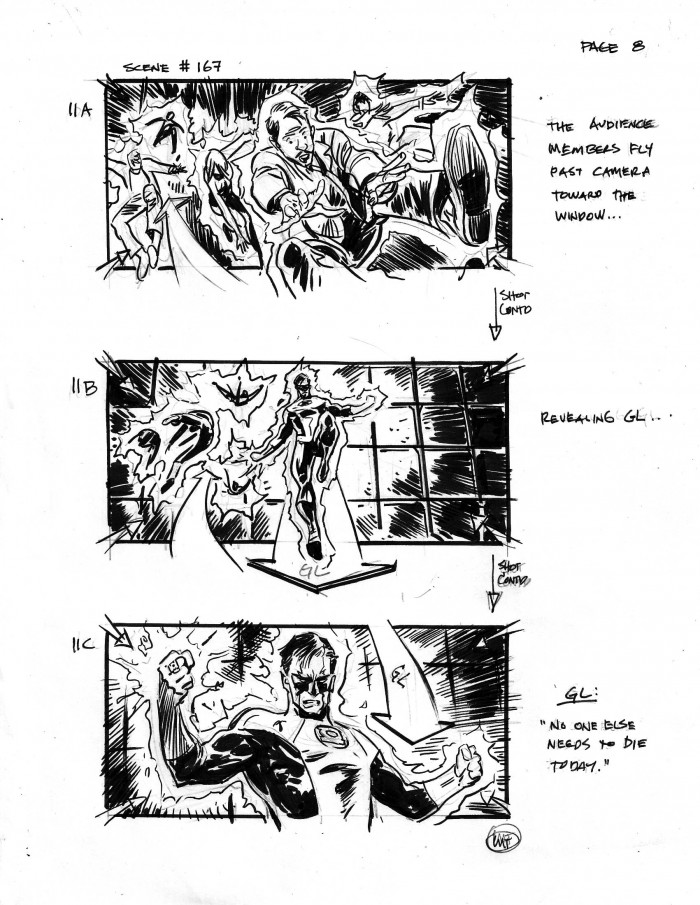

Blake Harris: I remember expecting Wild Wild West to be more like Maverick, but to your point it just fell flat. It lacked the same fun, adventure and excitement. But the point you make is very interesting because I suspect that gaging those qualities– fun, adventure and excitement—are probably very tough to determine during the process.Gabriel Hardman: It can be. Especially when you're not directly seeing how all these things connect. My biggest memory of Wild Wild West though was dealing with Barry Sonnenfeld, the director. You know, he had been the DP of the Coen Brothers' first couple of movies and then he went on to direct stuff. He wears a big cowboy hat and cowboy boots, but he's also a very neurotic guy. And my main memory was that I went to show him some boards right before they did the cast table read. At a Century City Hotel. And he's, like, trying to describe how the action in a scene will happen—a fight, with one guy on top of another—so he makes me lay down on the floor and he straddles me in front of everyone. It was humiliating.Blake Harris: That's a great first impression.Gabriel Hardman: Yeah, exactly. I mean, Barry is an eccentric character. I liked working with him though. I did the second Men in Black as well. Blake Harris: Another HDTGM movie you worked on was Green Lantern. But I was curious why you weren't credited on the film. Was that somehow intentional?Gabriel Hardman: No, not really. That kind of thing happens a lot. It's mostly probably because I worked on it for a few months when a different director was attached to direct it [Greg Berlanti]. It was more or less the same script as what was later shot. So I worked on it for a while, but it was kind of clear that the situation wasn't working out and they ended up shutting down the movie for a while and I went off and I did Inception. And when the movie came back up, it was with a different director and a whole bunch of different people working on it. There are a lot of things like that. And, you know, I'm not gonna go out of my way to get credit on that movie.

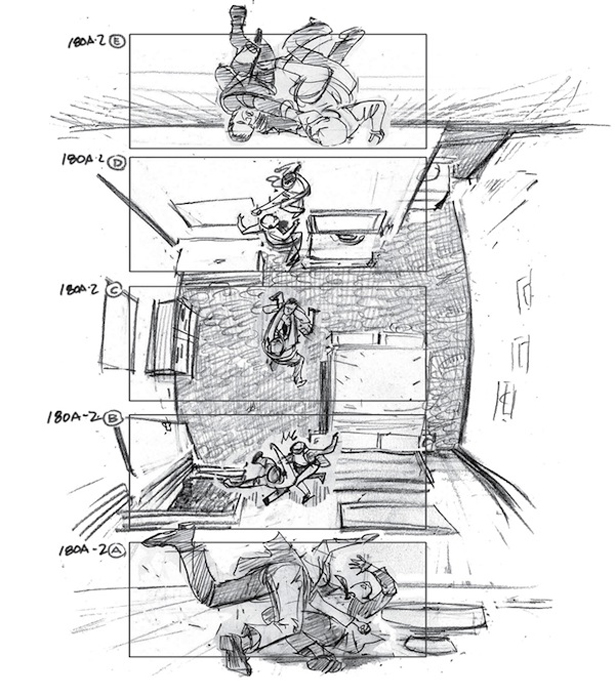

Blake Harris: Another HDTGM movie you worked on was Green Lantern. But I was curious why you weren't credited on the film. Was that somehow intentional?Gabriel Hardman: No, not really. That kind of thing happens a lot. It's mostly probably because I worked on it for a few months when a different director was attached to direct it [Greg Berlanti]. It was more or less the same script as what was later shot. So I worked on it for a while, but it was kind of clear that the situation wasn't working out and they ended up shutting down the movie for a while and I went off and I did Inception. And when the movie came back up, it was with a different director and a whole bunch of different people working on it. There are a lot of things like that. And, you know, I'm not gonna go out of my way to get credit on that movie. Blake Harris: That makes sense. Speaking of superhero movies, you also worked on Spider-Man 3. Which just so happens to be the only movie I've ever walked out on mid-filmGabriel Hardman: Oh, man. I spent about a year-and-a-half working on Spider-Man 3. Yeah, I mean, I think that it's tough to talk about that just because I spent so much time on it and there was such an immense amount of effort poured into it. I think Sam Raimi's a great guy and I really liked working with him—in addition to being a fan of Evil Dead and his earlier movies—but it was a very problematic movie and I believe Sam has said as much interviews since.Blake Harris: You obviously admire and respect Sam Raimi, but what's it like to enter a situation like there, where he's directed the previous two movies in the franchise, and you're kind of joining the party midstream?Gabriel Hardman: I was personally never a huge fan of the other Spider-Man movies. Just from personal taste, they didn't really work for me. But as I said, I respected Sam and admired his work. So even though the script was never finished and there were always many problems with it, my mindset was that whatever this thing is I'll just try to do my best for Sam. Maybe this will come together in a way that won't personally work for me, but will work for the people who were fans of the previous movies. But I'm not going to pretend that the movie seemed like it was anything other than a mess. It seemed like a mess. There were always big lingering questions about parts of the movie.

Blake Harris: That makes sense. Speaking of superhero movies, you also worked on Spider-Man 3. Which just so happens to be the only movie I've ever walked out on mid-filmGabriel Hardman: Oh, man. I spent about a year-and-a-half working on Spider-Man 3. Yeah, I mean, I think that it's tough to talk about that just because I spent so much time on it and there was such an immense amount of effort poured into it. I think Sam Raimi's a great guy and I really liked working with him—in addition to being a fan of Evil Dead and his earlier movies—but it was a very problematic movie and I believe Sam has said as much interviews since.Blake Harris: You obviously admire and respect Sam Raimi, but what's it like to enter a situation like there, where he's directed the previous two movies in the franchise, and you're kind of joining the party midstream?Gabriel Hardman: I was personally never a huge fan of the other Spider-Man movies. Just from personal taste, they didn't really work for me. But as I said, I respected Sam and admired his work. So even though the script was never finished and there were always many problems with it, my mindset was that whatever this thing is I'll just try to do my best for Sam. Maybe this will come together in a way that won't personally work for me, but will work for the people who were fans of the previous movies. But I'm not going to pretend that the movie seemed like it was anything other than a mess. It seemed like a mess. There were always big lingering questions about parts of the movie. Blake Harris: Like Peter Parker breaking into dance?Gabriel Hardman: It's interesting you say that. Because the notorious things that people don't like about it—like the dance sequence and stuff like that—that stuff was basically there the whole time. That's the stuff Sam was into. And I don't really begrudge him that. It might be perverse or too eccentric, but I liked the weirder stuff about it better than the bland superhero stuff. At least it's something different. I'm more forgiving of that than I am the really terrible melodrama and the weird amnesia subplot or whatever.Blake Harris: Although you weren't involved with Spider-Man or Spider-Man 2 did you get a sense working with those who had that this movie was coming out a bit different? Like was it all business as usual, or did they seem like problems in this instance?Gabriel Hardman: I would say they seemed like problems. In this instance, it very much felt like there were too many things—too many characters, too many plots—that didn't go anywhere. But I think in a lot of ways it was not...I mean, there are many factors that go into making a movie and it also has to do with being pushed, presumably, by the studio to make a thing that wasn't ready. It was meant to be two movies at one point and then got kind of kluged together into one. I also know there were bigger ideas about it when they started that just kind of didn't work their way into the thing. And, you know, they tried to do a 4th one, but just couldn't quite come to terms with the studio.Blake Harris: Were you asked to do the 4th one?Gabriel Hardman: They did, but I felt like I'd already done my time for Spider-Man.Blake Harris: Spending over a year on a film like that, I can't imagine how frustrating that must have been. Was there a single moment that stands out as the most frustrating of all?Gabriel Hardman: I don't think I can tell you the real one.Blake Harris: Ha.Gabriel Hardman: But let me tell you about the best experience I had on that film because it came about by accident. I went on a scout to New York with Sam Raimi, the 1st AD, the DP and a couple other people. And coming back, trying to get to the airport, for some reason we ended up late. We ended up not making the plane. Our flight was the last one out of Newark on a Sunday night, so the three of us—me and Sam and the 1st AD—wound up staying at, like, the Newark Airport Marriot. But the good thing about it was we just fucking went to the terrible restaurant at the Marriot and then hung out at the bar, and I ended up just sitting there talking to Sam; asking all these questions I had about those earlier movies he made. And just talking to this director that I liked when I was younger, for hours about The Evil Dead, that was wonderful. For all the terribleness and frustration of that movie, that was an awesome experience.

Blake Harris: Like Peter Parker breaking into dance?Gabriel Hardman: It's interesting you say that. Because the notorious things that people don't like about it—like the dance sequence and stuff like that—that stuff was basically there the whole time. That's the stuff Sam was into. And I don't really begrudge him that. It might be perverse or too eccentric, but I liked the weirder stuff about it better than the bland superhero stuff. At least it's something different. I'm more forgiving of that than I am the really terrible melodrama and the weird amnesia subplot or whatever.Blake Harris: Although you weren't involved with Spider-Man or Spider-Man 2 did you get a sense working with those who had that this movie was coming out a bit different? Like was it all business as usual, or did they seem like problems in this instance?Gabriel Hardman: I would say they seemed like problems. In this instance, it very much felt like there were too many things—too many characters, too many plots—that didn't go anywhere. But I think in a lot of ways it was not...I mean, there are many factors that go into making a movie and it also has to do with being pushed, presumably, by the studio to make a thing that wasn't ready. It was meant to be two movies at one point and then got kind of kluged together into one. I also know there were bigger ideas about it when they started that just kind of didn't work their way into the thing. And, you know, they tried to do a 4th one, but just couldn't quite come to terms with the studio.Blake Harris: Were you asked to do the 4th one?Gabriel Hardman: They did, but I felt like I'd already done my time for Spider-Man.Blake Harris: Spending over a year on a film like that, I can't imagine how frustrating that must have been. Was there a single moment that stands out as the most frustrating of all?Gabriel Hardman: I don't think I can tell you the real one.Blake Harris: Ha.Gabriel Hardman: But let me tell you about the best experience I had on that film because it came about by accident. I went on a scout to New York with Sam Raimi, the 1st AD, the DP and a couple other people. And coming back, trying to get to the airport, for some reason we ended up late. We ended up not making the plane. Our flight was the last one out of Newark on a Sunday night, so the three of us—me and Sam and the 1st AD—wound up staying at, like, the Newark Airport Marriot. But the good thing about it was we just fucking went to the terrible restaurant at the Marriot and then hung out at the bar, and I ended up just sitting there talking to Sam; asking all these questions I had about those earlier movies he made. And just talking to this director that I liked when I was younger, for hours about The Evil Dead, that was wonderful. For all the terribleness and frustration of that movie, that was an awesome experience.

Part 2: International Man of Artistry

Blake Harris: Before we talk about some more of the films you've worked on—and don't worry, the rest will likely all be better experiences—can you briefly explain the job and function of a storyboard artist?Gabriel Hardman: Sure. In essence, the job of being a storyboard artist is mostly about creating visual documents that the crew can look at to understand what the director wants to shoot. It's about laying out sequences from the film in visual terms. For camera, stunts, art department—everyone—so they can get an idea of what they need visually and technically for a scene. It has more to do with the nuts and bolts of filmmaking, or at least it does in theory. A lot of times, though, it isn't as orderly as that. Especially because scripts rarely include an abundance of visual details. It's often that I'm in a position of making things up or pitching sequences to the director; so it becomes very much about that dialogue. But the basic idea is that a storyboard artist is there to create a visual version of the screenplay so that everyone knows what's going on.Blake Harris: And was this something you knew that you wanted since you were a kid? Or more of an avenue that you discovered along the way?Gabriel Hardman: I've always been a huge movie fan, a cinephile, but I can't say that early on I had a specific job in mind. I should say, really, that I was always just very interested in visual storytelling. In addition to movies, I also always loved comics. I was a fan of comics when I was kid, but I generally liked the books that were less popular. Characters that never quite worked for whatever reason. The stuff that had the biggest impact on me—when I was around 13/14 years old—was probably Doom Patrol and Swamp Thing. Late 80's books at DC that were supposed to be more for adults. Probably because, as a young teenager, what appealed to me was the stuff that was just beyond my grasp. Blake Harris: How did you go from admiring these forms of visual storytelling to actually creating them yourself?Gabriel Hardman: I actually drew comics for a living when I was younger. I went to School of Visual Arts for a semester, but then ran out of money. And had been pursuing drawing comics for a living since I was 14 years old. So I was very serious, overly-serious even, about that kind of stuff. So starting when I was 18, I drew a book for Marvel called War Machine and worked in comics for a couple of years. And then the market for comics fell out in the mid-90s. So then I moved out to LA and told everyone I was going to be a storyboard artist. Though I didn't really have any idea how that was going to happen, nor made much effort to really make it happen.Blake Harris: So, without making much of an effort, how did it happen?Gabriel Hardman: Very unexpectedly. I was a big fan of Twin Peaks and the co-creator Mark Frost had written a novel. I was standing in line to get the book signed and was just chatting with a guy in front of me. I told him about how I wanted to be a storyboard artist and he said, "I know an agent that represents storyboard artists." He gave me the number and it was that same agent who later put Kazaam on my resume. Who, by the way, I got rid of shortly after that incident.Blake Harris: Once you started getting jobs, how was the experience different—or the same—as what you expected?Gabriel Hardman: Well, my expectations were that I would do very badly at it. Because I had huge problems with authority. So, in a way, I figured that while this sounds like a good idea, there's no way I'd get along with directors. I'd always had fights with my editors at Marvel. But that turned out not to be the case at all. There's a kind of seriousness and intensity that comes with making movies that suited me very well.

Blake Harris: How did you go from admiring these forms of visual storytelling to actually creating them yourself?Gabriel Hardman: I actually drew comics for a living when I was younger. I went to School of Visual Arts for a semester, but then ran out of money. And had been pursuing drawing comics for a living since I was 14 years old. So I was very serious, overly-serious even, about that kind of stuff. So starting when I was 18, I drew a book for Marvel called War Machine and worked in comics for a couple of years. And then the market for comics fell out in the mid-90s. So then I moved out to LA and told everyone I was going to be a storyboard artist. Though I didn't really have any idea how that was going to happen, nor made much effort to really make it happen.Blake Harris: So, without making much of an effort, how did it happen?Gabriel Hardman: Very unexpectedly. I was a big fan of Twin Peaks and the co-creator Mark Frost had written a novel. I was standing in line to get the book signed and was just chatting with a guy in front of me. I told him about how I wanted to be a storyboard artist and he said, "I know an agent that represents storyboard artists." He gave me the number and it was that same agent who later put Kazaam on my resume. Who, by the way, I got rid of shortly after that incident.Blake Harris: Once you started getting jobs, how was the experience different—or the same—as what you expected?Gabriel Hardman: Well, my expectations were that I would do very badly at it. Because I had huge problems with authority. So, in a way, I figured that while this sounds like a good idea, there's no way I'd get along with directors. I'd always had fights with my editors at Marvel. But that turned out not to be the case at all. There's a kind of seriousness and intensity that comes with making movies that suited me very well. Blake Harris: The first movie three movies you worked on were all comedies released in 1997. Mr. Magoo, Flubber and Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery.Gabriel Hardman: Yeah, Austin Powers was the actually the first. I had done a couple of little tiny jobs and a couple of commercials, but the first film I did was Austin Powers. And it was a relatively small movie. Non-union with a first-time director.Blake Harris: Yeah, it's hard to remember, but expectations were pretty low for the first Austin Powers movie. I mean, of those first three films you did, I don't think it would have been crazy to predict that Austin Powers would fare the worst. Compared to the stars of those other films—Robin Williams and Leslie Nielsen—Mike Myers probably had the lowest profile.Gabriel Hardman: At that point, Mike had made Wayne's World, which was very successful. But then Wayne's World 2 had not been so successful. And So I Married an Axe Murderer was definitively unsuccessful. So it was at a point where his "value" was pretty low. And, you know, he wanted to make this movie that made no sense to anyone.

Blake Harris: The first movie three movies you worked on were all comedies released in 1997. Mr. Magoo, Flubber and Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery.Gabriel Hardman: Yeah, Austin Powers was the actually the first. I had done a couple of little tiny jobs and a couple of commercials, but the first film I did was Austin Powers. And it was a relatively small movie. Non-union with a first-time director.Blake Harris: Yeah, it's hard to remember, but expectations were pretty low for the first Austin Powers movie. I mean, of those first three films you did, I don't think it would have been crazy to predict that Austin Powers would fare the worst. Compared to the stars of those other films—Robin Williams and Leslie Nielsen—Mike Myers probably had the lowest profile.Gabriel Hardman: At that point, Mike had made Wayne's World, which was very successful. But then Wayne's World 2 had not been so successful. And So I Married an Axe Murderer was definitively unsuccessful. So it was at a point where his "value" was pretty low. And, you know, he wanted to make this movie that made no sense to anyone. Blake Harris: It's very possible that seeing the trailer for Austin Powers was, as a kid, the first time I ever asked myself: How did this get made?Gabriel Hardman: Right, because you couldn't really frame what this movie was as something that was recognizable to people. And it was Jay Roach's first movie. It was my first movie. I was just a kid, only 21 or 22 years old; totally just bluffing and learning along the way. And Jay was actually great about it, about helping me out and teaching me. Being very forthright about what he was doing and very earnest about it. And I mean, he was just getting his shot. Which he barely got. He only got it because Bob Shaye at New Line gambled on him. He hadn't directed comedy, but he knew Mike socially and they'd just kind of worked on this. And the great thing about that was Mike was, he was very open to just talking about the stuff. We'd go over and hang out at Mike Myers house when we worked on sequences, you know? He'd make us watch the Francois Truffaut's 400 Blows over and over again, which I guess was some sort of inspiration for the movie that I could never figure out. And it actually turned out to be a really good experience.Blake Harris: What was it like working with Mike Myers?Gabriel Hardman: Mike is a very serious guy in a lot of ways. As a lot of comedians are. He's a really thoughtful, serious guy. And he thinks a lot about comedy theory. Talking to him about that sort of stuff was actually really interesting. Even over the course of the other two movies as well. Like one time, I think on the third one, he kind of cornered me in the hall and pitched me a gag—I can't remember which one—but it was sort of a question of do we reveal something to the audience first and then tell Austin, or the other way around? This elaborate sort of very thoughtful pitch to me. And I said, "Well you don't want to telegraph it. That might spoil the joke." And he responded right away saying, "That's absolutely wrong. Comedy is all about telegraphing." And went into a lengthy explanation about the mechanics of that, which I thought was actually pretty great.Blake Harris: I don't know if you'd remember this per se, but can you recall if Mike Myers already had Austin's character—the accent, the persona, etc.—locked in at the start, or was it more of something that evolved over time?Gabriel Hardman: He totally had the character right from the beginning. I know he'd performed it live in small places. To test it out. So I'd heard him do the Austin Powers accent a bit, but more so the Dr. Evil—Blake Harris: The Lorne Michaels?Gabriel Hardman: Right, the Lorne Michaels. And I remember knowing that it was Lorne Michaels early on. It wasn't like this was a big secret. Though he's not really a gregarious performer when he's not on set. And he's very much a, you know, a very perfectionist-oriented performer on set...he's sort of an intense guy.

Blake Harris: It's very possible that seeing the trailer for Austin Powers was, as a kid, the first time I ever asked myself: How did this get made?Gabriel Hardman: Right, because you couldn't really frame what this movie was as something that was recognizable to people. And it was Jay Roach's first movie. It was my first movie. I was just a kid, only 21 or 22 years old; totally just bluffing and learning along the way. And Jay was actually great about it, about helping me out and teaching me. Being very forthright about what he was doing and very earnest about it. And I mean, he was just getting his shot. Which he barely got. He only got it because Bob Shaye at New Line gambled on him. He hadn't directed comedy, but he knew Mike socially and they'd just kind of worked on this. And the great thing about that was Mike was, he was very open to just talking about the stuff. We'd go over and hang out at Mike Myers house when we worked on sequences, you know? He'd make us watch the Francois Truffaut's 400 Blows over and over again, which I guess was some sort of inspiration for the movie that I could never figure out. And it actually turned out to be a really good experience.Blake Harris: What was it like working with Mike Myers?Gabriel Hardman: Mike is a very serious guy in a lot of ways. As a lot of comedians are. He's a really thoughtful, serious guy. And he thinks a lot about comedy theory. Talking to him about that sort of stuff was actually really interesting. Even over the course of the other two movies as well. Like one time, I think on the third one, he kind of cornered me in the hall and pitched me a gag—I can't remember which one—but it was sort of a question of do we reveal something to the audience first and then tell Austin, or the other way around? This elaborate sort of very thoughtful pitch to me. And I said, "Well you don't want to telegraph it. That might spoil the joke." And he responded right away saying, "That's absolutely wrong. Comedy is all about telegraphing." And went into a lengthy explanation about the mechanics of that, which I thought was actually pretty great.Blake Harris: I don't know if you'd remember this per se, but can you recall if Mike Myers already had Austin's character—the accent, the persona, etc.—locked in at the start, or was it more of something that evolved over time?Gabriel Hardman: He totally had the character right from the beginning. I know he'd performed it live in small places. To test it out. So I'd heard him do the Austin Powers accent a bit, but more so the Dr. Evil—Blake Harris: The Lorne Michaels?Gabriel Hardman: Right, the Lorne Michaels. And I remember knowing that it was Lorne Michaels early on. It wasn't like this was a big secret. Though he's not really a gregarious performer when he's not on set. And he's very much a, you know, a very perfectionist-oriented performer on set...he's sort of an intense guy.

Part 3: Inception, Interstellar and Invisible Republics

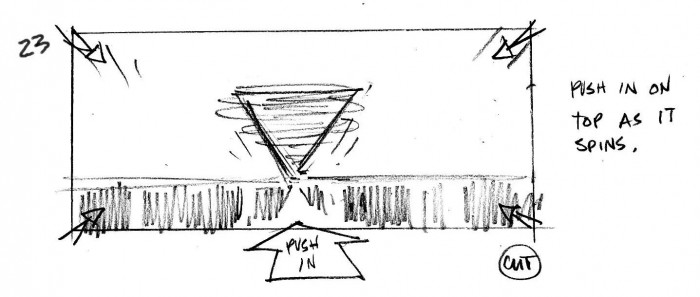

Blake Harris: Flashing forward about a decade, you started working with Christopher Nolan. You've storyboarded Inception (2010), The Dark Knight Rises (2012) and Interstellar (2014) for him. How did that relationship begin?Gabriel Hardman: I believe that Inception was the first movie that he prepped in Los Angeles, I think all the others had been done in London. And prior to Inception, he had never really worked with a storyboard artist before. But on that film, he wanted to do storyboards more seriously. I was recommended, I went in, I chatted with him and then they hired me. This was for Inception, so on the first day I went in and read the script. I then met with Chris and he asked me if I'd read it and I said I did. And then he was like, "But did you understand it?" [laughing] "Yeah, I think I did."Blake Harris: Ha! Gabriel Hardman: Inception was really up my alley for a lot of reasons. One being that it was an original screenplay. It's not based on anything, which is so rare these days. The number of times that I've worked on a film that wasn't based on some other property is very small. There are very few movies like that. So the idea that this was going to be a big sci-fi movie based on an original idea and an original script was really exciting.Blake Harris: When you read the script for a movie like Inception, or really any movie I suppose, are you thinking in terms of visuals are you're reading it? Or does that process start down the line?Gabriel Hardman: Sure, definitely. Chris's scripts tend to be very terse, so there were definitely things that were suggested in Inception, but there's not an inordinate amount of description on the page. And nothing had been designed at all at that point either. So it wasn't like I was seeing art from the art department. I was starting very cold. And the very first thing I worked on was the fight in the hallway, where the hallway's spinning. Or rather, as Chris described it, "It's not that the hallway is spinning, it's that the rest of the world is spinning." So the very first thing was enormously complex. I ended up doing like two phone books worth of storyboards—just every level of the dream. I kind of get a little punchy just thinking about it. Just so much to keep track of. But it was still really fun and exciting to work on. As were The Dark Knight Rises and Interstellar.

Gabriel Hardman: Inception was really up my alley for a lot of reasons. One being that it was an original screenplay. It's not based on anything, which is so rare these days. The number of times that I've worked on a film that wasn't based on some other property is very small. There are very few movies like that. So the idea that this was going to be a big sci-fi movie based on an original idea and an original script was really exciting.Blake Harris: When you read the script for a movie like Inception, or really any movie I suppose, are you thinking in terms of visuals are you're reading it? Or does that process start down the line?Gabriel Hardman: Sure, definitely. Chris's scripts tend to be very terse, so there were definitely things that were suggested in Inception, but there's not an inordinate amount of description on the page. And nothing had been designed at all at that point either. So it wasn't like I was seeing art from the art department. I was starting very cold. And the very first thing I worked on was the fight in the hallway, where the hallway's spinning. Or rather, as Chris described it, "It's not that the hallway is spinning, it's that the rest of the world is spinning." So the very first thing was enormously complex. I ended up doing like two phone books worth of storyboards—just every level of the dream. I kind of get a little punchy just thinking about it. Just so much to keep track of. But it was still really fun and exciting to work on. As were The Dark Knight Rises and Interstellar. Blake Harris: What's it like working with Christopher Nolan?Gabriel Hardman: He is an incredibly confident filmmaker. And he truly is a filmmaker; he understands what he's doing and he understands every part of the process; (so you're not going to be able to put anything over on him). And the biggest thing that distinguishes working on his films is something that I kind of touched earlier: the script. On all of his films, there is a finished screenplay at the beginning. Which is wildly different from most of the films I've worked on where, you know, there might be no third act yet. Everything is still changing and the movie is happening because the studio wants to hit a certain release date, not because there's a finished script that's ready to go. Obviously little things can still change on his films, but with Nolan movies everybody always knows exactly what the movie is that they're making.

Blake Harris: What's it like working with Christopher Nolan?Gabriel Hardman: He is an incredibly confident filmmaker. And he truly is a filmmaker; he understands what he's doing and he understands every part of the process; (so you're not going to be able to put anything over on him). And the biggest thing that distinguishes working on his films is something that I kind of touched earlier: the script. On all of his films, there is a finished screenplay at the beginning. Which is wildly different from most of the films I've worked on where, you know, there might be no third act yet. Everything is still changing and the movie is happening because the studio wants to hit a certain release date, not because there's a finished script that's ready to go. Obviously little things can still change on his films, but with Nolan movies everybody always knows exactly what the movie is that they're making. Blake Harris: I imagine that working on films like Interstellar, Inception or even Austin Powers—films that are well-received and also do well at the box office—must be pretty satisfying to you as both an artist and someone who needs to make a living. So what it's like when the opposite happens. As with, say, Spider-Man 3.Gabriel Hardman: I was incredibly worn out after that movie. With the whole idea of committing, literally, every waking moment to projects that I could often even tell weren't going to be too good. And so after Spider-Man 3, my wife Corinna Bechko—who's a writer—she had come up with a sort of atmospheric horror story. We just kept talking about it and decided to work on it together, turning it into a graphic novel. The appeal of just, the fact that I could sit down and just draw this story and it would be done and people could read it, seemed incredibly accessible to me. After spending all that time on Spider-Man 3, just sitting down and cleanly, clearly by myself telling a story was incredibly appealing. So we put that book and it was called Heathentown. And it was nice to do something that wasn't connected to a giant machine that costs millions and millions of dollars and was simple and straightforward and boiling it down to those storytelling ideas that I like in general.

Blake Harris: I imagine that working on films like Interstellar, Inception or even Austin Powers—films that are well-received and also do well at the box office—must be pretty satisfying to you as both an artist and someone who needs to make a living. So what it's like when the opposite happens. As with, say, Spider-Man 3.Gabriel Hardman: I was incredibly worn out after that movie. With the whole idea of committing, literally, every waking moment to projects that I could often even tell weren't going to be too good. And so after Spider-Man 3, my wife Corinna Bechko—who's a writer—she had come up with a sort of atmospheric horror story. We just kept talking about it and decided to work on it together, turning it into a graphic novel. The appeal of just, the fact that I could sit down and just draw this story and it would be done and people could read it, seemed incredibly accessible to me. After spending all that time on Spider-Man 3, just sitting down and cleanly, clearly by myself telling a story was incredibly appealing. So we put that book and it was called Heathentown. And it was nice to do something that wasn't connected to a giant machine that costs millions and millions of dollars and was simple and straightforward and boiling it down to those storytelling ideas that I like in general. Blake Harris: I can relate to that, the appeal of autonomy. But in this case, Heathentown wasn't completely autonomous as you were working with your wife. What was that like?Gabriel Hardman: Well, we still work on a lot of things together. Our current book at Image—Invisible Republic—that's something that we write together and I draw. It's been a really good experience. Probably because my wife and I agree on a lot of things, you know? With tone and stories and the kinds of things we like. That's why we got married, after all. You know, I didn't choose to get married to Sam Raimi. I think Sam's a great guy, but I don't think I have a lot in common with him sensibility-wise. Or at least the Sam Raimi of now. So working with Corinna was (and is) a very different thing because we are doing things that we both agree on with a shared sensibility.Blake Harris: That's great! I just have one more question. Once upon a time you worked exclusively on comics and then, for about ten years, you worked exclusively on films. So what's it like now to be working on both at the same time? Is it ever hard, or unexpectedly frustrating, to toggle between mediums?Gabriel Hardman: I think the thing is, for me, I have somewhat of a fine arts background, but everything I've done professionally has been about storytelling. Visual storytelling. So at a certain point it just becomes clear: cool shots or splashy pages don't really mean anything, you know? It's about whether you're effectively telling the story. Are you getting across the thing that you're supposed to be getting across? So it doesn't feel like much of a leap to go from one to the other because the challenge is never really about the visual spectacle of what I'm working on. It's very much about telling the story, that's what matters most of all.

Blake Harris: I can relate to that, the appeal of autonomy. But in this case, Heathentown wasn't completely autonomous as you were working with your wife. What was that like?Gabriel Hardman: Well, we still work on a lot of things together. Our current book at Image—Invisible Republic—that's something that we write together and I draw. It's been a really good experience. Probably because my wife and I agree on a lot of things, you know? With tone and stories and the kinds of things we like. That's why we got married, after all. You know, I didn't choose to get married to Sam Raimi. I think Sam's a great guy, but I don't think I have a lot in common with him sensibility-wise. Or at least the Sam Raimi of now. So working with Corinna was (and is) a very different thing because we are doing things that we both agree on with a shared sensibility.Blake Harris: That's great! I just have one more question. Once upon a time you worked exclusively on comics and then, for about ten years, you worked exclusively on films. So what's it like now to be working on both at the same time? Is it ever hard, or unexpectedly frustrating, to toggle between mediums?Gabriel Hardman: I think the thing is, for me, I have somewhat of a fine arts background, but everything I've done professionally has been about storytelling. Visual storytelling. So at a certain point it just becomes clear: cool shots or splashy pages don't really mean anything, you know? It's about whether you're effectively telling the story. Are you getting across the thing that you're supposed to be getting across? So it doesn't feel like much of a leap to go from one to the other because the challenge is never really about the visual spectacle of what I'm working on. It's very much about telling the story, that's what matters most of all.