'Dunkirk' Vs. 'Darkest Hour': How Christopher Nolan Succeeds Where Joe Wright Fails

It's one of those strange coincidences that occurs every few years: two different films cover the same subject matter and happen to be released in close proximity. Typically, it happens in big-budget situations – audiences were able to see two different movies about asteroids headed for Earth (Armageddon and Deep Impact) as well as two different movies about anthropomorphized ants (Antz and A Bug's Life) in 1998. This year, something similar is happening and even more remarkably so. Two very different, very British films cover a specific period in World War II: the evacuation of British soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk, France.

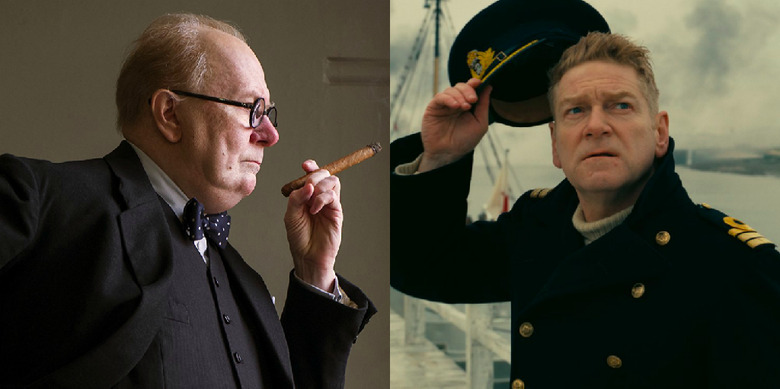

This summer, Christopher Nolan delivered his latest big-budget affair, the relentlessly intense, excellent Dunkirk; Joe Wright's Darkest Hour, currently in limited release, follows Winston Churchill as he makes the decisions that would kickstart the Dunkirk evacuation. The difference between the two films is stark.

In Atonement, Wright spent a few minutes depicting the carnage at Dunkirk in a virtuosic if show-offy single-take shot featuring one of the main characters (James McAvoy) wandering around shell-shocked. Now, Wright focuses squarely on the British leaders, specifically new Prime Minister Winston Churchill (Gary Oldman), who find themselves in a difficult spot. The United Kingdom, in May of 1940, had been boxed in by Hitler and the Nazis, who were invading other Western European countries, and decided to evacuate as many troops as possible and fight on.

What is so remarkable about Dunkirk, especially in opposition with Darkest Hour, is its tightened focus. Even in dividing the story into a triptych (set in the air, on the sea, and on the land), Nolan's story is about the men on the ground, in a seemingly hopeless situation with no chance of survival. There are so many stories about World War II, so many depictions of the leaders in the United Kingdom and America trying to maintain a stiff upper lip and do what's right even if it's also what's difficult, that Dunkirk stood out. By eschewing exposition — we barely know the names of the men onscreen, and after a brief opening title card explaining the situation, there's not much more than a smattering of dialogue — Nolan's film stands apart from almost every other film in the genre.

Darkest Hour comes from a director whose visual style is already remarkable enough. Joe Wright's made some singular films in his 12 years of features, from the aforementioned Atonement to his best film, the warped spy fable Hanna. Even within the staid and stodgy drawing-room wartime drama within which Wright has to operate, Darkest Hour looks remarkable. Cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel utilizes shafts of light bursting through the haze and grimy dustiness of WWII-era Britain to emphasize Churchill's unique standing in UK politics. However, so much of Darkest Hour feels like the umpteenth iteration of the same period drama that has seemingly existed to garner awards buzz, as if it should have been titled Oscar Bait: The Movie. It's a feeling that extends all the way to the film's centerpiece, Gary Oldman's performance as the larger-than-life Churchill.

Oldman is one of the finest actors of his generation, and he has delivered a searing and complex performance as a character ensconced in British politics at a time of great international tension. Unfortunately, that performance was in the 2011 adaptation of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, and it was sadly overlooked for the Oscar, even though Oldman got his first (and currently only) nomination. He will no doubt receive a nod for Darkest Hour; if nothing else is true, he almost certainly can claim the award for Most Acting this year. Thanks in no small part to some very good prosthetic makeup, Oldman is transformed here as Churchill, tweaking his voice and jutting out his lower lip just enough to suggest the former Prime Minister. Churchill is a character with an extremely small amount of subtlety, a figure as outsized on film as he was in life. Yes, it's an impressive transformation, and yes, Gary Oldman is good in Darkest Hour. But that's because Gary Oldman rarely phones in his work; of course he's good here. How could he not be?

The lack of subtlety extends to the rest of Darkest Hour. Churchill, like many historical figures given the biopic treatment, has a family that always plays second fiddle to him, led by his always loving, if slightly vexed wife (Kristin Scott Thomas, who deserves better, as usual). In one early scene, after Churchill is given the title of Prime Minister, his wife congregates their family to congratulate him while acknowledging that they have all made sacrifices to allow him to further his career. (There is a seemingly notable insert shot of one of Churchill's adult sons having a large swig of alcohol, as if to suggest the toll those sacrifices take, but it comes to nothing later on.) This, in effect, is the film's screenwriter, Anthony McCarten, trying to both have his cake and eat it too. See? This movie is aware of the trope of the ignored family! But here's the thing: just because your movie points out that the main character's family is being ignored doesn't mean you get a pass when you ignore his family. Considering that Churchill's children only appear in this one scene, it's even more unnecessary to call attention to the fact that they're overlooked.

Of course, Winston Churchill's family isn't the focus in Darkest Hour; instead, it's all about what led Churchill to push for the impossible in evacuating soldiers at Dunkirk. The circumstances that led to this dangerous decision were impossible. As they're presented in Darkest Hour, it's suggested that if Churchill doesn't extend the possibility of brokering peace talks, two of the higher members of his Conservative Party, Viscount Halifax (Stephen Dillane) and former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (Ronald Pickup) will resign, suggesting that the current leader has no confidence from his own people. Seeing as we're more than seven decades removed from World War II, and nearly eight decades removed from the heroic and miraculous evacuation of Dunkirk, it should not be a spoiler to suggest that a) Churchill did not engage in peace talks and b) the soldiers were almost entirely rescued, vastly more than were initially expected.

In Nolan's Dunkirk, we don't see how this particular sausage gets made. One of the focal characters, a pilot played by Tom Hardy, is given orders by a military leader (Michael Caine in a voice cameo) early on. In the film's final moments, as in the final moments of Darkest Hour, we hear Winston Churchill's address to Parliament and the world, suggesting that the fight will wear on until the Nazi threat is wholly removed. But in Dunkirk, whatever inspiration there is to latch onto is not borne of politicians coming together to take down a fascist threat. There is simply the straightforward, unfussy heroism of the human spirit.

In Darkest Hour, that speech is meant to rouse British politicians to full action, even the previously unwilling Chamberlain. In Dunkirk, when that speech is recited, it comes at the end of the visceral rescue mission and has a bittersweet tinge. Yes, the soldiers were rescued, and yes, the feats of bravery from regular people are rousing, but many of the film's characters suffer some kind of loss.

Darkest Hour tries to have a truly goosebump-inducing, rah-rah moment in the final third. Churchill has had his own spirits boosted slightly when King George (Ben Mendelsohn, also underused but very good) affirms his support for the Prime Minister, who he previously deemed "scary," but recommends he talk to the average Britisher to see if they would rather fight the Nazis or broker peace. Churchill does, by descending into the London Underground, hopping onboard a train and reaching out to a random assortment of 10 or so British citizens. All of them, from a feisty young girl to an older working-class man, firmly push to fight fascism in a scene that is meant to be stirring and winds up as almost a parody of the clips played on Oscar night to highlight nominated performances. Knowing, as we do, that the British kept fighting makes the scene more than a little inert. So too does the sense that Churchill could easily have bluffed his way through convincing his conservative brethren about going to war instead of encountering a smattering of regular folks. What should be inspiring comes off as treacly and overdone.

Part of the problem has little to do with Darkest Hour, and everything to do with Dunkirk. In a year with Christopher Nolan's stripped-down exercise in tension, a film that sidesteps so many of the trappings of the period drama and the wartime epic, another movie covering the same subject matter even in a different light is bound to fall short. And so it is with Darkest Hour, which often feels like it exists solely to garner Gary Oldman a long-deserved Best Actor Oscar. He does deserve one, and it's mystifying that, as of this writing, he just has the one nomination. But if he wins for Darkest Hour, it will feel more like a lifetime achievement award, instead of an award specific to this role. Joe Wright is still a talented director, but he's unable to transcend the dryness of McCarten's script, which feels like the umpteenth version of a story that could just as easily be an HBO Movie of the Week co-produced by the BBC. Where Dunkirk felt like it was breaking ground, Darkest Hour feels like it's following a well-worn, overly familiar path.