Dissecting Three Of The Scariest Stephen King Movie Moments

Being scared is a highly subjective experience. Some people have a genuine fear of clowns. For those people, the coulrophobics of the world, watching the new film adaptation of Stephen King's It in a theater full of clowns would probably be terrifying. The rest of us will just have to be content to get in the mood for It some other way. A great way to do that is by revisiting scary scenes from other Stephen King adaptations.

With that in mind, let's dive into a few memorable moments from other Stephen King adaptations and talk about how those moments play into certain indelible fears. Some of these fears might register on a basic human level; King would not be as successful as he is if he were not capable of tapping into the kind of horror that does that. Other fears might seem more perspectival in nature; but here again, King would not be as successful as he is if he were not capable of shifting the axis of a reader's perspective from time to time.

Let's attempt something similar. Let's put you in the shoes of a contestant on a Fear-Factor-like show, set entirely within King's world of horror. Here, the contestant is forced to confront a succession of elemental fears, one after another.

To keep it accurate, we'll follow the format of a real Fear Factor episode, and limit the list to three stunts, or fear challenges. Even if you are not wired to have the same fears — even if these are not the same King moments that would rank with you personally — maybe they will start to resonate, and you will start to feel a little sympathy or even empathy for our beleaguered fear contestant (let's call him Grifty McFear).

Now, let's run the gauntlet ...

The Mist (2007)

Fear challenge #1: The fear of hopelessness.

Key quote for this challenge: "Four bullets."

Throughout this list, we'll be moving backward through the decades, and so the first title to come up is this 10-year-old film from director Frank Darabont. Before he developed The Walking Dead into a TV show, Darabont had made a career of adapting Stephen King stories for the big screen. His first two adaptations, The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile, were both nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards.

The Mist is more of a B-movie, complete with dodgy special effects, like the squirming CGI tentacle that drags a character out of the garage in a supermarket where people are taking refuge from a mysterious fog with monsters in it. But while the film would not get nominated for any Oscars, there are some flourishes to it, like the heavily improvised camerawork, that do elevate it above the usual horror fare, both stylistically and thematically.

When Darabont made this film, he was coming off a stretch where he had just directed several episodes of the television crime drama The Shield. Much of the crew for The Mist was in fact made up of Shield personnel, and the show's influence can very much be felt in the film's ragged camera approach. As the characters start to get caught up in mass hysteria at the supermarket — with Mrs. Carmody, the deranged, Bible-thumping ring-leader, inciting stabbings and calling for "expiation" — the camera is right there in the middle of the chaos. There is a feverishness to the way it pivots and zooms. Darabont went in guerrilla-style, without blocking the shots, letting the lens participate in the delirium.

But it is the film's divisive, unflinching ending that truly elevates it. Gentle reader, we are about to delve into some serious spoilers now, so if you have not seen The Mist and do not want to know the film's ending, do yourself a favor and skip to the next fear challenge.

Walking Dead fans will recognize Laurie Holden and Jeffrey DeMunn, who played Andrea and Dale on the hit show, as two of the faces in the escape car when it runs out of gas in the middle of the mist. Up until this point, the movie has been all about survival. But now, when faced with the seemingly hopeless prospect of abandoning the car and taking their chances against the mist monsters, the characters give in to despair and make a suicide pact.

The only problem is, there are not enough bullets in the gun that David Drayton, played by Thomas Jane, is holding. And so he must do the unthinkable: shooting his four friends, including his son, and then offering himself up as the sole survivor to be devoured by the mist monsters.

The scene plays out like a tragedy, with Drayton resigning himself to his fate and embarking on an irreversible course of action, only to get out of the car, see the mist clear up, and realize help was right around the corner in the form of tanks and military men. By then, his situation really has become hopeless: not because it was that way to begin with, but because he himself made it that way.

In this fashion, The Mist restructures the fear that all hope is lost into a fear of giving up hope, abandoning it of one's own volition. At the same time, it also plays into another fear: the fear of folly. That feeling of, "Oh, my God. What have I done?" It shows how fragile a person's decision-making process can be when beset on all sides by monstrous problems.

Can we trust ourselves in moments like that? What if our instincts mislead us, even deceive us, to make choices that will let us down in the ugliest way possible?

The film's feel-bad ending is one for the record books, yet in showing us the folly of what Drayton does, it manages to make a powerful allegorical statement about not letting oneself lose hope. Because we could all be him. We could all be that person struggling for survival, driving through life with a fog over our future, tempting us to give up hope.

Through the folly of its characters, The Mist illustrates a kind of worst-case scenario, the waking nightmare that can result, when a person gives up hope. In a weird, roundabout way, it is almost life-affirming. By building up Drayton's fatal blunder, illustrating the ultimate example of what not to do, it lets us as audience members learn from the tragedy of a fictional character's mistake, reinforcing the need for perseverance in our own lives.

Even though the ending is different, it is worth noting here that in his original novella for The Mist, King literally gave "hope" the last word. The Shawshank Redemption was also based on a novella with the phrase "Hope Springs Eternal" in the subtitle.

Misery (1990)

Fear challenge #2: The fear of powerlessness.

Key quote: "Paul, my little ceramic penguin in the study always faces due south."

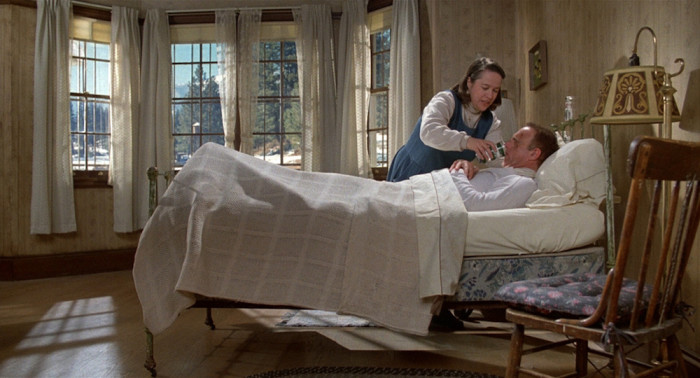

This one might seem like a no-brainer. In the movie, a successful romance novelist named Paul Sheldon, played by James Caan, is taken captive by his "number one fan," after a car accident leaves him temporarily bed-ridden. So clearly he is the one without power: the film is all about how powerless Paul is forced to endure his utter lack of control in increasingly horrific ways. Right?

On the face of it, yes, but when you dig a little deeper, it becomes clear that the film is not as simple or one-sided as that. Misery works on other levels, too. Sure, the aforementioned "number one fan," Annie Wilkes — brought to life by Kathy Bates in a performance that won her the Best Actress Oscar — comes across as a force of nature. Through most of the film, she is constantly asserting dominance over Paul, making him burn his manuscript, dictating the new one he will write, etc.

The scene where it all comes to a head has become known as the "hobbling scene." After Annie abruptly drugs him, Paul wakes up to find himself strapped to the bed, with her cooing, "Paul, I know you've been out. You've been out of your room." She then starts talking about how native workers in diamond mines were once punished for stealing in a way that ensured they could go on working. "The operation was called hobbling," she explains as she forces a piece of wood between his ankles. Then she lifts a sledgehammer and starts swinging away, making good, bone-crunching work of his ankles.

Annie Wilkes is in total control during this scene. Her victim, poor powerless Paul, thought he had gotten away with sneaking out of his room while she was gone, even though he accidentally knocked over a ceramic statue during his big wheelchair adventure through the house. But then she comes back and delivers that line: "Paul, my little ceramic penguin in the study always faces due south."

This is a fascinating, unforgettable line, all the more so because it shows that Annie Wilkes is a woman with OCD tendencies, and therefore not in control at all.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder, or OCD, is all about the illusion of control. People who suffer from it often find themselves vying for mastery over one manageable thing in an otherwise messy universe. If they can control that thing, they feel better. It gives them a sense of being in command over their tiny corner of the cosmos. That is what Annie does with Paul: she makes him her pet OCD project, going to great lengths, all throughout the film, to keep this unwieldy, objectified man in her tenuous grasp.

In her own way, however, Annie Wilkes is just as powerless as anyone else. Think about it from her perspective. Here is this disgraced nurse, living all alone out in the middle of nowhere, before she randomly stumbles into the opportunity of a lifetime.

There he is: her favorite writer, left incapacitated by a car wreck. This is her chance! She can control something! Like those helpless infants she nursed back at the hospital.

Annie Wilkes got lucky, that is all. But eventually, her luck would run out in the face of life's unpredictable flow. From the macro level of the audience, we can see it — it bears the markings of a movie plot — but from the micro level of her character, she could not foresee that her pet OCD project would be her undoing. Obsession is like that; it consumes people.

Paul devises a scheme to escape, and this time, he outwits Annie and gains the upper hand, bashing her over the head with a typewriter. Score one for the agent of life. Now it is Paul who takes on the aspect of a force of nature. In the end, Annie Wilkes would prove herself no more capable of controlling life than any other OCD person. What a miserable fate for Misery's monster...or was Paul the real monster all along?

The Shining (1980)

Fear challenge #3: The fear of family.

Key quote for this challenge: "All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy."

It's an odd turn of phrase, the fear of family. Family-phobia: what kind of goofy sitcom fear is that? But in some of King's early work as a writer (see also the 1978 short story "The Boogeyman"), there is a definite theme of men wanting to unburden themselves of responsibility and be free of their families. Like Misery, however, The Shining is not bound by one perspective. It works from multiple angles on the fear front.

The character of Jack Torrance, as embodied by Jack Nicholson, clearly resents his wife and son. An important element of his backstory is an injury he inflicted on his son when the boy got into his papers and made a mess of them. When his wife interrupts one of his writing sessions at the Overlook Hotel, he also lashes out at her viciously.

For Jack, family is an object of fear, to be reviled, insofar as it is capable of endangering his work. His barely repressed anger comes from the way he perceives his wife and son as interfering with his duties as writer and caretaker. Though what we see in him is obviously warped, that sense of aspirational drive might actually be relatable to anyone who has ever had trouble juggling their professional life with their home life.

A busy adult who still clings to personal ambition could easily find their parental and spousal obligations weighing down on them like hindrances. There are only so many hours in the day, and when a person does not have enough time to pursue his or her dream, family relationships and other social obligations like friendships might come to be regarded — rather irritably — as human obstacles on the road to success. So it is that Wendy and Danny Torrance would, from Jack's perspective, seem to impede his goals.

He may not have invented the term "ball and chain," but he certainly wears them like one. Simply put, Wendy and Danny take all the fun out of Jack's life. He can't drink when he's around them. He can't write. He's got to work to feed them. "All work and no play ..."

The problem is, Jack is a monster. We see it in Wendy's eyes as he catches her flipping through his typewritten manuscript, with pages and pages of the same quote, "All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy," written in different margin settings.

"How do you like it?" he asks, creeping up on her from behind, his voice piercing the heavy silence in the Overlook's lounge.

Only now does Wendy realize her husband has lost it completely...if he ever really had it to begin with. And there is a sustainable argument that he didn't, at least in Stanley Kubrick's version of The Shining, which strayed from King's original intent. To paraphrase a quote, the Overlook didn't change who Jack was; it revealed who he was. It showed that his writer act was all a big sham, and he was really just using his family as an excuse for why he had failed in life.

The slow walk up the staircase — Jack gibbering beyond reason, Wendy swiping at him with the bat — is unbearably tense. "I'm not going to hurt you," Jack says. "Wendy, darling, light of my life." He is saying all the things that a loving husband should be saying, but the tone is all wrong, cruel and mocking. There is something wrong with him as a person.

Here again, we see the fear of folly — self-delusion, misplaced trust in people, whatever form it takes. Wendy's own blindness betrays her. She married a monster; she sees that now. But it is too late. She is trapped with him under the roof of this place. It's the perfect metaphor for a bad marriage. To say nothing of the abuse aspect.

That is what makes it so scary when Jack goes after Danny in the hedge maze at the end of the film. Because Danny was born into this family. Unlike Wendy, who could have chosen to leave her husband, Danny had no choice in anything. Maybe Dick Halloran could have hooked him up with a lawyer who would give him some sage counsel about the emancipation of minors. But Dick Halloran took an ax to the chest, leaving Danny on his own to contend with the person who was supposed to be his protector.

That is the other way The Shining taps into the fear of family, by showing us the horror through Danny's eyes, putting us in the shoes of a kid running through the snow from his father. As one commentator in the documentary Room 237 points out, it is only by retracing his steps, going back over his footprints in the snow, that Danny can escape what his father represents. A parent is a provider, but they can also be a conduit, revisiting the sins of the past on their children. Is it any wonder that the Danny of Doctor Sleep, King's literary sequel to The Shining, wound up alcoholic, like his dad?

The fear of family is a fear, not just of faulty DNA, but of cycles of behavior, the vicious circle that often perpetuates itself through families across generations.

Last month, I wrote a whole Unpopular Opinion article about the TV version of The Shining and how it is a worthy companion piece to Kubrick's film. I would have very much loved to include a scene from that miniseries on this list: specifically, the scene that plays out in the forbidden Room 217. I still maintain that the moment when the little boy tries to will or wish his fears away by closing his eyes — only to pull back the shower curtain and see a woman's living corpse lying in the bathtub — remains one of the more terrifying things to have been shown on network television in the past 20 years.

"Hello, Danny. I've been waiting for you. We've all been waiting for you."

Here, as in the aforementioned "Boogeyman" short story, King expertly manipulates the fear that the nightmare is real. Your fears are valid; the monster is there, peeling off the mask of a trusted therapist, to reveal the boogeyman underneath. The way the woman in Room 217 rises up out of the bathtub, the way her decomposing foot touches down on the bathroom tile, is absolutely mind-boggling when you think about it in the context of an impressionable teen watching it at home on a school night, circa 1997 (and again, on network TV, not cable or a premium channel).

Those are the subjective circumstances under which my 16-year-old self experienced that scene. In the final analysis, maybe viewing conditions are as much a factor in being scared as the actual content of some horror films. It all depends on where you are (if you're alone, if it's dark) and who you are (if you have any deep-seated fears or personal hang-ups, how young and impressionable you were when you watched a given scene.)

So what are your picks for the scariest Stephen King moments?