'Die Hard' 30th Anniversary: The Cast And Crew Reflect On The Making Of An Action Classic [Interview]

(This week marks the 30th anniversary of Die Hard, arguably the greatest action movie of all time. To celebrate, /Film is exploring the film from every angle with a series of articles. Today: the cast and crew look back on the making of an action classic.)

John McTiernan's 1988 action tour de force is one of my favorite movies ever made. It's a masterclass on every level: building entertaining characters, crafting escalating action, establishing and navigating geography, and putting an empathetic hero through the ringer in the face of extraordinary odds. McTiernan and his collaborators made this all look easy, but as the rash of Hollywood imitators that followed quickly proved, it was anything but.

Die Hard turns 30 years old this weekend, and to celebrate, I spoke with cinematographer Jan de Bont, writer Steven E. de Souza, and actor Reginald VelJohnson (who played Sergeant Al Powell) about why the film still holds up, how some of its most memorable scenes came together, and much more.

As originally envisioned, this piece would have featured quotes and anecdotes from one person seamlessly flowing into stories and recollections from the next, sort of like the oral history format I used when I wrote about the incredible throne room lightsaber fight scene in Star Wars: The Last Jedi. But each of the participants in these Die Hard interviews were so gracious with their time and had so many distinct stories to tell that it would have done them a disservice to blend them all together. So instead, I'm going to present the highlights from my conversations with each person one at a time.

Note: These interviews have all been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Jan de Bont Die Hard Interview

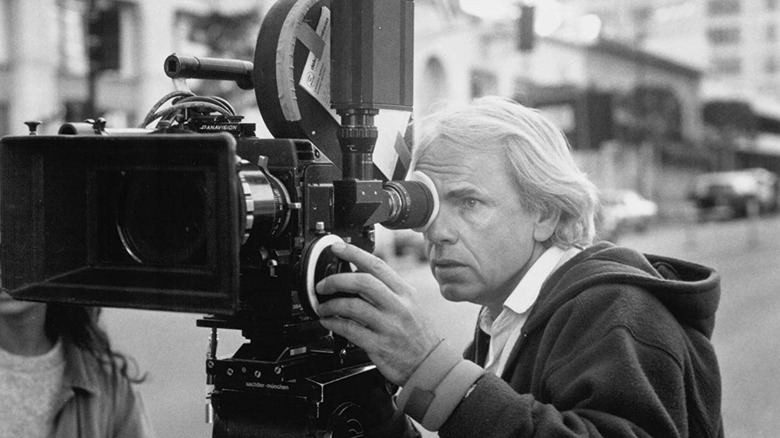

First up, here's my chat with cinematographer Jan de Bont. De Bont went on to become a notable director in his own right with films like Speed and Twister, but was a key part of crafting the look of McTiernan's classic. He told me about how he made an office building look cinematic, the power of shooting real explosions, and how the production used experimental military technology to film one of the movie's most iconic shots.

/Film: Before you started production, did you take a look at any other films or have any visual inspirations for the movie?

Jan de Bont: Basically, it always comes down to the screenplay. Of course, I was a fan of American movies, and especially like the more realistic type of action movies, and Die Hard – the script itself – was something that I thought, the moment I read it, I could create a visual style that would be really perfect for the time. Where everything is so direct and very intimate, in a way. The camera is almost taking part in the action itself. Most of the film is shot handheld, there's very close distances, the camera feels and moves around the actors in a way as if it is a third person participating in all of it. That makes it really interesting.

I also felt that, when I talked to John [McTiernan], I said, 'We need to do this all on location. No matter the location, we have to make this look real. Because if this film doesn't look real, it's going to be just like another action movie that we've seen so many of.' And he totally supported that. And at that time, handheld was not used [very often] – it happened after, and was copied many times, but before that, it wasn't really used. People didn't think like that. It was such a big movie, you couldn't do that. You had to treat it more like a regular stylized film like people had seen before. This was a moment in time where, basically, film was already on the verge of transitioning from analogue to digital. I always felt that this could be one of those last movies that still could really showcase all the advantages of analogue filmmaking.

John McTiernan has said he didn't really storyboard this movie. Do you remember any conversations you had with him about specific shots in the film?

We didn't storyboard much. The good thing is that John and I had such a great relationship, and to me, it's always a matter of trust. When you storyboard the movie from beginning to end, I feel, as a DP, the movie has been made. So why would you get involved? Somebody else can do it. For me, you make the decisions on the set of how you're going to do it. There's no way in the world that a storyboard artist can imagine what an actor's going to do, what the set will look like exactly, what the relationships between the characters will be. That's how you have to film on the set, and the camera has to relate to that. You always have to see where everybody is at a given time in relationship to each other. Otherwise, you have all this confusion. I hate confusion in movies, where we have no clue where everybody is.

John gave me an incredible amount of freedom in that way. We talked about it before – every day, we drove to the set together and talked about the scene and what was important, what are the key elements, what we had to make come across and how tense it had to be, or was this scene a bit more relaxed. We talked more about the emotional and the suspense character of the scene, not so much, 'Then a close-up of this, then a medium shot, then a wide.' We never thought in those ways. Those were really great conversations in that regard between us, and really important.

One of the things I was surprised to learn about Die Hard was that a lot of it was essentially crafted on the go. The script wasn't fully finished yet when shooting began. When did you know you were going to be able to use Fox Plaza for filming?

Actually, relatively late. We were looking at so many locations. The building itself is a character in the movie, so the character had to be seen and showcased. You needed the building to have character, and at the same time, we needed a building that was available [laughs] and was partially empty. So it was fantastic that, after all the locations we looked at, that was right next to us the whole time. What is so fantastic about that building, I think there were four or five stories occupied at the time, and many stories were still under construction. So we could use all of the floors that were not built yet and use them as set pieces.

Also, what is so nice about the building is that it had to be seen from far away. When Bruce sees it in the very beginning – when [limo driver Argyle] drives the car toward it, you only see it from a distance. As it comes in, the audience starts to get ideas about, 'This building is special.' Ultimately, it is. The whole story takes place in this one building, inside out, and what's also important is what you're seeing out of the building, you could see the outside. We weren't in a studio looking at a blue screen or a green screen. It was always real. To make that real, the windows had to be extremely clear at night scenes and very filtered during the day time so there was a balance between inside and outside. We had to change those windows on two floors regularly. All the windows. It really felt like you were looking down and, there's the city down there! That creates a lot of reality that is so much more important than cutting away and going to different locations.

Sort of along those same lines, Die Hard is regularly mentioned in terms of great action movies that do an excellent job of establishing the geography of every scene. At every point, the audience is aware of where they are in the building. How were you able to execute that?

Yeah, that's exactly right. Basically, as much as you can – for instance, the sequence when the helicopter comes in and lands on the roof – when the cameras are following and the actors inside go out to it, we know how high it is that they have to go. We've seen the staircases before. We really made an effort to showcase what floor we were on. We know where everything is, so that when those helicopters come in and we see those people come up from the floor down below – and that whole sequence is done in two and a half takes with 24 cameras all at once with no digital effects – everything is real. We're on the roof and see the helicopter above, you can see it from below at the same time. There's no cutting away and no feeling of 'This was filmed two days later.' No. It's all there. You see the same people from both angles at the same time, which is so fantastic. For audiences, they know there's a reality to this. It is basically like the camera is as caught in the building as the people are.

Can you talk about filming the explosions in this movie? There are a ton of them, and they all look very real. Were any shot on models or miniatures?

The only one that's shot on miniature is the very top of the building. [laughs] Obviously, we couldn't blow up the top of the building. But many other ones in the building are actually real explosions. For instance, when the police come in with that vehicle and [Hans Gruber's henchmen are] shooting those rocket launchers at it, that is all real. We actually blew out all the windows on one particular floor. We did film those rocket launchers on a thin wire and torched that car. The audience knows the building so well that you can't fake it anymore. The car goes up the real steps of the building, and the rocket comes right to that car and explodes, and all the windows blow out at the same time, too.

Unfortunately, that was a very scary undertaking because it was a brand new building. [laughs] What's going to happen when all of the windows are blown out at the same time, and how to time it with the regular special effects guys? They did a fantastic job. It all happens almost casually, you know? We don't make such a big thing of it. It happens, and then boom – we're already going on to the next thing, so it's not like Bridge on the River Kwai where it takes you twenty minutes to set it all up and then finally, finally, finally, it comes and the bridge explodes and the train goes down. No, this all happens much quicker and it's much more real. That is a very unique approach to action movies.

I've done later movies with a lot of visual effects, but nothing is as good as the real effects. Anything you do with digital effects, in a split-second you can immediately see and feel that it's fake. Also, for the actors, it isn't possible to act accordingly to the quality of the effects. Quite often, nobody knows yet what they're going to look like. You can say, 'Oh, this will happen,' but how can you respond to something that hasn't been made yet and hasn't been created? It's impossible for actors to really become great in those movies. In this movie, the actors have to respond to the real thing. They are very close to those explosions. They're on top of a real elevator going up and down!

You were talking about the exterior of the building and how it plays a character in the film, but in terms of the inside of the building, an office building can pretty easily become a pretty boring environment. How did you go about making it an exciting environment? I know you were responsible for a lot of the smoke we saw in the movie in those hallways and pipes, but what other tricks did you use?

That's a really good point and a really good question. Offices usually use fluorescent lights in the ceiling, and that makes almost every room look the same. So what I did is, in those hidden ceiling pockets, I hid film lights. Very little ones that were all on digital dimmers, so I could set levels and create darkness and bright spots wherever I wanted it to be. The last thing I was trying to do was get this overall boring white light where every room looks the same. Quite often, for instance on the empty floors where there's no lights yet, I could play with that. The fluorescents would lay on the floor in the frame as if they were just there to be installed the next day. So you could play with positions of lighting that you normally would not have if the building was completely already finished. So I could light it dramatically and play with it in any way.

I could change light settings during the shot, even. It's really hard to have those big sets lit for everything at the same time, so quite often you have to dim and move things around while the camera pans from one to the other. That was a complicated set-up, but once you get used to it, the electricians all knew what to do. They realized very quickly how it had to work. Basically, all the lights are built into the set and the location, but you can never see them unless they're hanging from the ceiling or broken or things like that. That's how we were able to create an atmosphere that is more dramatic.

Was it in the script to have those burning pieces of paper floating around in the background during that big climactic showdown?

No, a lot of things weren't in the script. [laughs] You asked how the script could change so much during the filming itself, and in a way, for this movie, it was really good. Because when Bruce Willis came into the set, he was available like three days before the movie started. He had just done the series Moonlighting and he wasn't a known person for films yet. So everybody had to get to know him, and we had to see how he could play the character and what would work for him, and that was the same for all the characters in the movie. So the first week is always a bit of experimenting, and then you see how characters relate and how they talk. The dialogue had to be rewritten many, many times as we got to know the actors and felt what was write for them to say. Often you'll read a script and have all those great lines, but if you hear them on the set, they're so out of place that you have to change it.

So a lot of things were changed, and we were lucky having that building there that was still mostly empty, where we could do that. If all the sets are built and you have no more freedom, then it's really, really hard. But we had this great opportunity to work and see what the tension between the two characters are. You don't know until you see those two actors together. It's still more or less the same story, but the intensity of the scenes have changed quite a bit.

The sequence where Hans Gruber falls at the end: I've heard there was a countdown for that and Alan Rickman was released at an unexpected time to get his real reaction as he fell. Is that true?

Yeah, and it was really difficult. When you see those shots happen, it's always on blue screen, and we wanted – the most important reaction on a person's face is the first second. If a person falls down away from camera in free-fall, it goes at such a high speed that you cannot get the focus right. That's why nobody ever does it. So we had to design a system where there's a computer that tries to set the focus to the rhythm of the speed he is falling, so we had to do a couple different tries for different people. It was a really difficult rig because nobody had ever done that, and it was a really big close-up. I don't know if you remember, but it's right in his face, right in his eyes. It's also in slow motion, so anything that would be out of focus would be out of focus for a long time. The focus was so difficult and no focus puller could ever get it right. It'd be impossible. We were finally able to do it correctly.

And yes, you should never tell [an actor] exactly when [you're going to drop them], because if you say, 'We're going to drop you at 3,' then they're always going to respond a fraction of a second early. Quite often it's better to wait a little bit, do '1, 2, 3...' and then the actor tends to get a little confused, and then you drop, and then you get the best reaction. [laughs]

The thing about the focus pulling is amazing. I've never even thought about that before, but of course that must have been incredibly difficult to do.

It is, because it goes so fast. It starts maybe two feet away from the lens, and then he goes from two feet to seventy in no time. So if you want every little frame of that, hundreds of frames, to be in focus, it's like, an impossible task. It was basically something that was invented for the military, I think. They were just experimenting with that, a little company in the Valley. They had never done it for film either, they had done it for some kind of video shoot for the military. But they adapted it for us, and ultimately it worked.

Did you do a lot of testing and prep with that before you got Alan Rickman hooked up? How many takes did he do?

I think he did three takes. Sometimes, the first take is often a surprised reaction. But we didn't want just surprise. It had to be the realization that he was going to die. You have to give the actor...in a case like this, it's almost better to have them make sure that when he falls, he's going to be safe when he hits the bottom. Because he's going to fall on a big airbag way down there. Most actors are so worried about all of those stunts, and rightfully so, and they should be done safely. Once they know it's safe, they can act. But then you still have to time it right. So you still have to surprise him when it really goes.

What did you learn making this movie that you brought with you in the rest of your career?

I think flexibility is the most important thing. It's not a thing that's high on the list of possibilities on those big budget movies. Flexibility? That's the last thing they want, because they want everything to go according to plan. But certain things had never been done before, and we did things where while we were shooting, we quickly did a tryout of a scene somewhere else to make sure that the next day, that effect might work. We were totally prepared to move very quickly from the 43rd floor to the 39th floor, so we could move very fast.

Flexibility – if things don't work, immediately thinking of another way to solve it. If it doesn't work, don't just accept it. Find a way to get it right and make it meaningful and dramatic and suspenseful. That's really key. Never cave in. Make sure you get it right.

Why do you think this movie still holds up so well 30 years later?

I think the viewer is pulled into the movie, basically, because it's at a relatively high pace and it moves all the time. And it moves in a way where they are seeing something new and they have to pay attention. Quite often the audience will just sit and watch and don't participate in the movie, and I really like very much if the audience has to make an effort to really go along with the movie, with the storytelling, with the way it's visually told. I think that's really, really important, especially for today's audiences. Let them not only enjoy it, but let them make an effort to follow the story and feel the tension. Every shot in this movie has a certain suspense and tension. [When I saw it recently], I was surprised how it's still such a good movie! It still holds up so well. It still feels fresh, which is very hard to say of movies that are thirty years old.

What is the thing that you most proud of regarding Die Hard?

What I really liked about it was that it was never about making beautiful shots. It was always about making shots that are dramatically important. Any cinematographer knows that it's great to make beautiful shots, but it's also a little boring. Beautiful shots tend to take you away from the story, it distracts you. I much more like dramatic shots, where things are darker or you can't see very well or there are flares in it. All those flares in the movie, too, those are on purpose, by the way. Because it's real – that's how it would happen. When things happen quickly, you have flares. That's like what we have in real life, too. When you're at night and you see police cars coming, all you see are the flashing lights and the flares, you can't see everything correctly. That tension, that drama, is not about beauty. It's really about visual urgency, and that visual urgency makes this movie such a great picture.

Steven E. de Souza Die Hard Interview

Next, I spoke with screenwriter Steven E. de Souza (far right in the photo above), who was hired to apply his signature style of blending action and comedy to a rewrite of the existing script. He cleared up a persistent myth about the movie, explained how Bruce Willis was pulling a Michael J. Fox (filming a TV show during the day and the film at night), and recounted how one of Die Hard's best scenes came about because of one crew member's offhanded request to hear Alan Rickman's American accent.

/Film: When the crew was filming Argyle driving John McClane to Nakatomi Tower in the beginning, nobody knew how he was going to factor in at the end of the plot. I tend to think about movies that start filming before they have answers like that as more of a modern thing, like a production trying to hit a pre-planned release date, so it's interesting that Die Hard had those same issues.

Steven E. de Souza: I think in this case, because there was a scramble to get the star – you know the story of how they went to Frank Sinatra first. There are a lot of mysteries and rumors. Even though I've had interview after interview, there's this fantasy, this myth that Die Hard was the Commando sequel script recycled. That's not true. Were you going to ask me that one?

No, but I'm glad to have you confirm once and for all that it's not true.

OK. Anyway, just because it happened so quickly, that may have been why it happened. At that time, the character didn't have anything else to do. He just got trapped in the garage. The ambulance idea, you know about that? That came late. Once, out of desperation, we went to the ambulance idea, that created an opportunity for Argyle to participate in the heroics because we were down to the last 10 days of filming, and it was the only place we could insert the idea. We were looking for places to put in the dialogue that they were going to escape in their own fake rescue vehicle, but it seemed so clunky to have Alan Rickman say it when he has his gun on Holly. So if we just showed it, we didn't have to explain it. The audience could figure it out. Of course, to show you how late that idea came to the picture, when the villains first step off the truck, there's no ambulance [hidden] in the truck.

Why do you think Die Hard holds up so well after thirty years?

First of all, it ticks several genre boxes. I know people say it's an action movie, but there's a lot of suspense in it. It's as much a thriller as it is an action movie. When you think about it, the limited landscape almost fights the idea of it being an action movie, which usually has wide open spaces, a lot of running around, car chases, so on and so forth. There's also a love story, there's a lot of humor in it. In the Venn diagram of popular film genres, it covers several.

Die Hard is a prime example of a movie everyone cites when they're talking about films that actually take the time and care to establish the geography of the action. How did that translate in the script?

I would say that with John McTiernan and Spielberg and some other directors, you know exactly where everybody is, so when chaos breaks out, you know which end is up. Is this hero in danger? Are the villains getting close? What's interesting about Die Hard, John McTiernan and I and the stunt team walked throughout the entire building. So we had reality printed on our minds. There was a draft of the script that was written without any knowledge of where the building would be, which was Jeb Stuart's draft, but he was never in the real estate to really finesse what happened. I had a blueprint of the building that I was given. You know how Hans Gruber is always looking at the map of the building and talking to his guys? We really did that with the blueprint of the building. What happens is, because we go through a lot of the real estate repeatedly, after a while, the audience gets a sense of the geography of the building.

Another things that I think enriches the movie is all of the subplots. That is a direct result of the picture starting so late that they could not organize Bruce's schedule to become completely free of the TV show Moonlighting. When the movie started, he was still on Moonlighting. Remember, a lot of the movie is filmed in the actual building at night. The exception is the main room where the party is and the office when the sun is going down in the background – that's a set. But the rest of the picture, it's the real building at night. So Bruce is filming Moonlighting in the day time with a ten hour shoot, and then he's filming this thing. So after the first week, John McTiernan came to me and said, 'We have at least another week of this overlap. Why don't you go back into the script and see if you can find more stuff for all the other characters to do?'

That led to more scenes at the house with the housekeeper, it led to building up the idiot newscaster, and it led to some of the great scenes between Holly and Hans Gruber. I just invented her coming to the fore to protect her people. The instigation for that scene was not, 'Let's really develop this character,' it was, 'We're killing Bruce Willis!' [laughs] Powell was always in there, but under that direction, I ended up giving him more interaction with the cops on the ground, and there was some comedy that came out of that. But any time it's night time and Bruce is not in the shot? He was home sleeping. He was not on the set. We gave him time to recover.

One of my favorite scenes is when McClane encounters Gruber upstairs and Gruber pretends to be an American. I've heard that scene was your idea – is that true?

[Here are] Joel Silver's three rules of action movies. Number three is: we're going to get an R rating anyway, so let's see some hot babes. Number two is: shoot as much comedy as you can. If it's too much, you can cut it out later. And number one is: these movies are hate movies. They're like romance movies, only they're hate movies. In a romantic picture, a boy and a girl have a meet cute, they have several dates, and they go off together. In a hate movie, they have a meet cute, they have several dates, and one kills the other. The problem with this picture was, how can we get them together where Bruce doesn't die, because the other guy has a dozen people with him and complete control of the real estate?

One day on the set, we took a break in the afternoon while they were moving the camera. Someone said to Alan Rickman, apropos of nothing, 'Alan, a lot of UK actors do American accents.' This was his first movie, remember, so nobody really knew him. 'Do you do an American accent?' And he said, 'I don't know if I do an American accent, per se, but I do a California one.' And he did one like the skit from Saturday Night Live, "The Californians." So I dropped my sandwich and said, 'Oh my God.' I ran over and found Joel on the set, and brought him back and said, 'Do that again.' Rickman does it again, and Joel says to me, 'Yeah, so?' And I'm like, 'So?' and before I could explain it, he says, 'Oh! Oh! You're right! You're right! Get McTiernan!'

So we got him and asked Alan to do it again, and he said, 'Why are you doing this to me?' And I said, 'If McClane only knows Hans as this disembodied voice on the walkie talkie, if Hans can do this, they can meet. If we can contrive a way for them to them to meet, he can mind-f*** him!' John [thought about it], and said, 'No, McClane saw Gruber kill Takagi.' I said, 'Did you shoot that yet?' The first assistant director said they were going to shoot it the next day. [So they came up with] a way to shoot that scene so that McClane didn't see Alan Rickman pull the trigger, so they could meet later.

[That scene where they meet] ended up being in place of a scene where McClane met and killed Theo, the computer guy. That's another thing we did – as the picture was proceeding, based on the performances we were getting, we decided to keep certain people alive longer. The actors brought more fun to them. We said, 'OK, we've gotta kill somebody every ten or fifteen minutes, but let's kill this guy instead of that guy.' Anyway, we already had the feet bloody scene, so instead of meeting and killing Theo, [McClane met Gruber].

Reginald VelJohnson Interview

Finally, I spoke with actor Reginald VelJohnson. He played Sergeant Al Powell, McClane's lifeline on the ground as the madness unfolds in Nakatomi Tower. We talked about incorporating his tragic backstory, filming Powell's breakthrough moment at the end, and his relationship with Bruce Willis during the production.

/Film: Your performance provides an anchor for both John McClane's character outside the building, and really for the movie itself. Seeing all of that bureaucracy unfold, it's nice to know there's someone on the outside who gets it. Did you understand that was part of what you guys were doing outside of Nakatomi Plaza at the time?

Reginald VelJohnson: No, I didn't. I actually just was doing what the director told me to do because it was my first big movie role. So I really didn't investigate what the role was doing in the movie, I just did exactly what he told me to do.

Were you able to lock into your character and understand him right away? I know sometimes it takes a little while to ease into a portrayal.

I didn't do it right away. I didn't realize he was an integral part of saving Bruce's life in the movie until toward the end. It was my first big movie role and I didn't really understand what was going on.

John McTiernan has talked about how important it was for the relationship between McClane and the villains to be very serious, and for the humor to exist on the periphery. What do you remember about filming the comedic sequences with the police chief and the FBI agents?

I didn't realize how important my part was to Bruce's character until he was in the bathroom when his foot was cut and he was sitting in the bathroom sink. That's when I realized, 'Oh, OK, my character is an integral part of the movie.' It was interesting dealing with Bruce and the director and the same time and finding out where my character fit in. I'll never forget that, realizing how important the role was to the whole movie. It's kind of like I wish I could do it again so I could do a better job. [laughs]

We find out that Al Powell's backstory involves him shooting a child. Was it surprising to see that idea become even more relevant in recent years?

Yeah, when I was doing it, Powell shooting a kid was an important thing for me. I wanted to make sure that people got that, and they did. It was interesting for a cop to admit that at the time, and John McTiernan took a lot of time to make sure that part of the movie came out the way it did. I do remember him giving me a lot – this is 30 years ago, wow – giving me a lot of interesting things to do with that situation in the movie.

Like what?

The actual words. "I shot a kid." I had never really experienced a cop doing that before. A cop shooting a kid was a heavy thing, and I wanted to make sure that came across well.

What was your relationship like with Bruce Willis while making this movie? Did you two do anything to build your camaraderie off screen?

I was very intimidated by him in the beginning. He was a star, and I didn't know what he wanted out of me. But he was very, very nice and very careful with my character, telling me what he wanted me to do. That was it – it was really cool working with him. As a matter of fact, I'm going to be doing a tribute to him, the Comedy Central Roast, soon, but he was very giving and caring with me in the movie and I really appreciated that from him. I never got a chance to tell him how much I appreciate how he treated me. Because it was his first big thing, too. I was just there. I was just curious as to what was going on, and didn't realize how big my role was.

There's something so satisfying about watching Powell's arc unfold during this movie, because he's really like the co-lead of the film. Even though he doesn't enter the story until later, we arguably know as much about him as we do about McClane.

Wow, I didn't realize that. I had heard that the role was given to Gene Hackman and he couldn't do it or something like that, and they decided to cast a regular guy, which was me. They told me to put a cop uniform on and parade around in [the producer's] office. I think they made the role bigger than it was when was originally written because they didn't know exactly what to do with the character, and I guess they got me (laughs) to give them what they wanted, so I'm glad I did it.

I loved Family Matters and I know that show was a big part of your life, but does anyone ever recognize you on the street for your work in Die Hard these days?

Oh yeah. I was just in the supermarket and a guy told me how much he enjoyed Die Hard. I got Family Matters because of Die Hard, actually. The producers saw a screening of it before the movie came out, and they cast me to play Carl Winslow, and I didn't realize that. I found that out later on. To do a role that well and that effectively has been a blessing to me, and I never got another role like that ever since then, and I don't think I ever will. It was a good role, and I was nominated for an NAACP Award. I didn't get it, but just the idea that they nominated me in the role was an honor.

Why do you think this movie holds up so well thirty years later?

I guess because Bruce played a part that he never played before. I think it was the first time that the regular guy saved the day, so to speak. There weren't that many projects with that kind of character in it when the movie came out. I think Bruce playing an everyman kind of guy who triumphs by his own [wits] was a fresh thing at the time. I think people hadn't realized how important it was that you stand up for yourself when you can, and I think when it came out, people really gravitated to him doing that. That's what made him a star.

We talked a bit about the serious aspect of Al Powell's character, but there's a lot of comedy for him as well. Do you remember doing any improv or suggesting any jokes or alternate readings?

It was all scripted. I was too nervous to suggest anything at the time! I didn't really get comfortable doing the role on my own until toward the end of the movie. I just listened to the director and the producers. Joel Silver was the producer, and he did a lot of planning and telling us what to do, and I was just there listening and saying, 'Yes, sir!' I was just nervous about doing the job since they gave it to me, I wanted to make sure I did a good job.

The scene at the end in which Powell and McClane meet for the first time and Powell is able to pull his weapon again in the face of danger – what do you remember about filming that?

Shooting the gun. I was very nervous about having to hold the gun, and the special effects guys were showing me how to handle it. That was very nerve-wracking for me, I was trying to make sure I held that gun right. I didn't realize that the scene became an integral part of the movie until I saw the movie.

William Atherton, who plays the newscaster, was in Ghostbusters, and you were in that movie too.

Oh yeah! I didn't realize that until somebody pointed it out to me, but he was sort of a...he sort of played his role perfectly. [laughs] He was kind of like that. We didn't have much to say to each other on either project. I'm sure he's a very nice guy, I just never really spoke to him.

I just didn't know if you two made eye contact on the Die Hard set and gave each other a nod of recognition.

[laughs] No, we didn't. We were just trying to get it done, man. He was just doing his job and I was doing mine. I never really had the chance to speak to anybody or build camaraderie with anyone. Except Alan Rickman, he was a very nice guy. We would always talk and have a nice time during filming. He was an interesting fellow. I enjoyed working with him, God bless him.

When you look back on your work on Die Hard, what are you most proud of?

I'm most proud of the movie itself, actually. I enjoyed working on a project that became a classic. I didn't realize what kind of a classic it would be while I was doing it. And working with the director, working with Bruce and Bonnie [Bedelia]. Bonnie was a sweetheart. I just remember the experience of putting it all together. I go back sometimes and look at Nakatomi and wave to it as I pass by.