Road To Endgame: 'Captain America: Civil War' Is Marvel's Long-Term Payoff To A Political, Personal Post-9/11 Narrative

(Welcome to Road to Endgame, where we revisit the first 22 movies of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and ask, "How did we get here?" In this edition: Captain America: Civil War pays off years of build-up by injecting politics with personal impulse.)The Marvel Cinematic Universe tries to re-invent itself every few years, albeit within a limited narrative formula. From scrappy "real world" solo films, to fun, landscape-shifting crossovers, to alien family dramas, the series has been laying track for its two-part finale — Avengers: Infinity War and the upcoming Avengers: Endgame — for quite some time.A decade of narrative investment in the superhero genre, especially in a series that aims to be so political, can't be achieved without a feeling of loss. Last year, after having been scattered by the events of Captain America: Civil War, the Avengers were finally defeated.While no Avengers lose their lives in Captain America: Civil War, the team tears itself apart from within; they may as well have lost their identity. The series' long-term personal and political narratives finally boil over, clashing with one another for reasons both idealistic and petty, opposing impulses that are (rightly) framed as a continuum. It's a harrowing watch at times, despite building on its predecessors' confused politics. Debates about military intervention rage on in the real world, and as of Avengers: Age of Ultron, the Avengers' legacy finally began to stand in for America's. That legacy is complicated, and Civil War finally grants the series an element it had been missing for nearly a decade: deeply personal drive behind political ideology.

The Soldier

In Civil War, Captain America's (Chris Evans) journey away from blind nationalism comes full circle, though it leads him to an unsettling place: now a self-appointed interventionist, he represents American militarism once more. It's a fine line for a narrative to walk, one the film acknowledges by positioning its well-meaning, destructive protagonist at odds with his equally well-meaning-yet-destructive teammates. None of them are particularly wrong, and for once, a Marvel film being unable to draw a singular conclusion about military power feels textually justified.After a botched mission resulting in civilian causalities, the Avengers are put on notice by a returning General Thaddeus "Thunderbolt" Ross (William Hurt), now the U.S. Secretary of State. Ross, who was last seen in The Incredible Hulk, is all too familiar with the dangers of unchecked power. He hands the Avengers the Sokovia Accords, an agreement signed by 117 countries that would place Steve Rogers and his team under U.N. supervision.The Accords makes sense, at least in theory. A U.S.-based private military outfit has no business running unchecked missions on foreign soil, especially when they're half the reason these villains crop up in the first place. Like several other films in the series, Civil War differentiates between the American government and a fictional group meant to stand in for its faults. However, it articulates the retaliatory element of geopolitical conflict that's often ignored in western cinema, especially in the Marvel series.Military-funded Marvel movies like Iron Man, Iron Man 2, Captain America: The Winter Soldier and Captain Marvel were each made from scripts approved by the U.S. Department of Defense. In the first three of these films, global military conflict was framed either a status quo for American forces to respond to, or as flames stoked by outside actors for selfish motives, rather than something America had a hand in. In Civil War however, the first villain the Avengers face has a personal grudge against Captain America. From the perspective of Brock Rumlow, a suicide bomber, Steve Rogers is the reason he's scarred, and exists without a country. Later in the film, primary villain Helmut Zemo (Daniel Brühl) is revealed to have a similar vendetta against the Avengers; Zemo's family was collateral damage to the Avengers' reckless interventionism.Captain America isn't keen on being supervised. Not out of some vaguely jingoistic notion of "freedom," but because he's seen the American agenda change over time, both in The Avengers and in Captain America: The Winter Soldier. This leaves him in an interesting position. He is, at once, opposed to the U.S. government's idea of militarism, as well as its very embodiment, ready to go to war at a moment's notice.Rogers opposes the corruption and duplicitousness that often drive foreign intervention, while still adhering to its core methodology. In prior films, Steve Rogers was never given a clear ideological enemy, and so his own outlook was never allowed to grow beyond the broad strokes of power. Here, as if to finally course-correct this omission, the series uses his divestment from ideology as a dramatic question: who does Captain America truly fight for, if not interests he, and he alone, deems worthy?

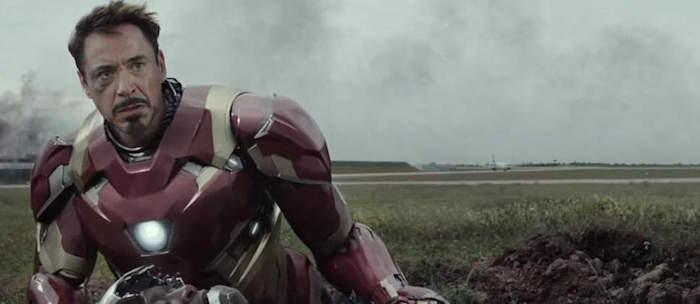

The Futurist

Like Steve Rogers, Tony Stark (Robert Downey Jr.), a former arms supplier, comes back around to embodying an element of the U.S. military apparatus. But where Rogers represents interventionism, Stark now represents the government control to which he himself was once so thoroughly opposed.Time and time again, Stark has seen his technology misused. In his previous appearance, Avengers: Age of Ultron, he created an antagonistic A.I. that nearly destroyed the world. Ultron was defeated, but not everyone got out of Sokovia alive. When confronted with the death of one such individual — Charles Spencer, a young American on a mission to build affordable housing — Stark's guilt finally forces his hand.No more private militarization. No more unilateral intervention. The Avengers need oversight — but under whose authority should they be placed? The group wouldn't be needed in an ideal world, the kind of world that has been Stark's objective since Age of Ultron, but the old world of war and misery is one he helped create in the first place.For Steve Rogers, doing the right thing means refusing to compromise on his moral outlook. For Tony Stark, doing the right thing means correcting his mistakes. The overlap between these objectives is where the film's conflict is born. Both men were reminded of their missions by their dying mentors — Abraham Erskine in Captain America: The First Avenger, Ho Yinsen in Iron Man — and those missions, which now form the core of who they are, have finally collided.Rogers, once loyal to the structures of western government, has been forced to turn against the very idea of structured power. Stark, once a man obsessed with his own unchecked might, now believes it's time for governments to take charge. Not only have Rogers and Stark seen the folly of their ways — having faced the most dangerous parts of blind loyalty and deregulation respectively — they now see the worst parts of their own past decisions within one another.

The Personal Behind the Political

Per the words of the late Peggy Carter (Hayley Atwell), Steve Rogers must remain an uncompromising protector, and respond to those telling him to move with a resounding "No. You move" (a line taken straight from the Civil War comics). When Black Panther (Chadwick Boseman) tells Rogers to move in Germany, he refuses. When Iron Man tells him to move in Siberia, he refuses once more.In either case, Rogers is protecting his best friend Bucky Barnes (Sebastian Stan), whose crimes, both recent and in the past, may not be his own. Rogers' uncompromising loyalty to Barnes, however, is a character flaw that functions the same way blind nationalism would. Captain America may no longer serve the stars and stripes, but he's shackled by the same emotional instincts.Rogers knows that people need to be protected, and he refuses to wait for their safety to be debated by committee. This is his overarching political outlook as it pertains to the Accords, but it's rooted entirely in personal bias. He took similar unilateral action to save Barnes during World War II, and he carries this lesson forward in a more complicated world he doesn't fully understand. He could be right about circumventing approval to save lives, but he may be right for all the wrong reasons.For Tony Stark, a man trapped by traumas and past mistakes, the guilt of his actions has become too much to bear. No matter how many times re-lives the past through virtual reality — like his final conversation with his parents — he's unable to change it. The only results of his obsession are a broken relationship, and an electromagnetic headache that he nurses with pills. When confronted by the mother of Charles Spencer, who blames him for her son's death, he has no choice but to try and fix the future. Though, his reasons aren't so forward-thinking.The Accords aren't just a political document for Stark. They're a means for him to prevent more damage to his soul. Not long ago, Stark was America's military industrial complex. Now, he's a protector unable to move past his own destruction.Getting the Avengers to sign the agreement may not prevent future tragedy — as Rogers rightly asks, what if the Avengers aren't where they need to be, or intervene somewhere they shouldn't? — but it's a step that shifts the responsibility away from Stark and his team. It's selfish, but it's exactly what Stark needs, though he's unprepared to admit it. Wanda Maximoff's (Elizabeth Olsen) civilian casualties in the name of protection would have been equally tragic if the mission were approved by a governing body, but at least Stark would have a clear conscience.Where Steve Rogers' political outlook is rooted in attachment to the past, Tony Stark's is grounded in his desire to detach himself from it.

The Plot

When Steve Rogers is close to signing the Accords, he's forced out of his decision by factors that feel like personal affronts, whether Tony Stark imprisoning Wanda at the Avengers' compound, or military forces going after his wrongly accused friend, Bucky Barnes. Rogers knows Barnes to be innocent, both for prior crimes in which he was denied autonomy, and for the recent U.N. bombing that killed Wakanda's King. Signing the Accords, at first, could result in Rogers being sidelined, and in lethal military force being used on Barnes instead.If Rogers waits to be taken in, or if he waits for a committee to decide on whether to intervene in Zemo's apparent plan (the re-awakening of more Winter Soldiers), the world could be at risk. If Stark doesn't stop Rogers from his reckless mission, the unstable, malleable Barnes could cause further harm, and the Avengers could be shut down for good.This rift is why the massive airport fight ensues, between those loyal to Captain America — Barnes, Wanda, The Falcon (Anthony Mackie), Hawkeye (Clint Barton) and Ant-Man (Paul Rudd) — and those who have fallen in line with Iron Man and the Accords — Black Panther, War Machine (Don Cheadle), The Vision (Paul Bettany), Black Widow (Scarlett Johansson) and Spider-Man (Tom Holland). Both parties are "right," in that they're justified from their own perspectives, which makes the ideological conflict between the two factions engaging. Additionally, Captain America is the film's protagonist, and so we, the audience, have the same information he does about Zemo's plan — information Iron Man's team does not.This lapse in information adds stakes to the narrative, over and above the enjoyable cognitive dissonance of good guys squaring off. However, the set-piece itself, while a fun reprieve from the conflict (and some of Marvel's most enjoyable action since The Avengers) remains disconnected from the rest of the film. Light-hearted though it may be, it feels half-hearted too. It's laden with Marvel's signature quips and rip-roaring action beats, but dramatizing interpersonal conflict through action might have been a more suitable choice. The Avengers fight, but nobody really seems in danger — Hawkeye and Black Widow even joke about pulling their punches — which works in opposition to the film's own premise about the consequences of these battles.The scene does eventually shift toward a more serious tone while setting up the climax — an untrained Vision accidentally injures War Machine, thus solidifying Stark's position — but the scene lacks any real emotional punch until that point. The airport sequence, fun as it may be, is at odds with what follows. It's immensely rewatchable on its own, but in-context, it's lacking. The film's ensuing rug-pull reveals that both sides were factually wrong. In effect, they aren't fighting for the people anymore. They're just fighting, as they were in the Civil War comics, though their battle on the page carries far more weight than their battle on-screen. The futility of their violence in the film is overshadowed by the fact that it feels like an enjoyable field trip.Thankfully, the film proceeds to foreground its emotional heft in the scenes that follow, as the story is re-framed in a manner that makes the next battle between heroes — Iron Man and Captain America — feel appropriately harrowing. By shifting its major set-piece to the middle of the film, Civil War also sidesteps a climax steeped in Marvel's signature pre-visualized action, the kind often divorced from story. Instead, the film narrows its spotlight to focus on a tale of deeply personal conflict.

Mission Report, December 16, 1991

Helmut Zemo's mission is complicated. It depends on dozens of moving parts, and on the Avengers making precisely predicted decisions. Zemo claims to have studied the Avengers closely, so his place in the narrative is as much a scorned antagonist as it is an invisible, meta-textual hand (Your mileage may vary). His scheme feels improbable in the real-world, but guiding the Avengers to these specific outcomes feels less like plot contrivance and more like catalyzing that which was already narratively inevitable.Every decision Zemo orchestrates is rooted character, set up not only during Captain America: Civil War, but across multiple films. He convinces Tony Stark, with his newfound sense of authority, to believe he's the only one who can stop a dangerous fugitive. He also makes Steve Rogers believe his friend Bucky Barnes (the very mention of whom blinds Rogers' decision-making) is in grave danger. He makes Captain America's side of anti-establishment, gung-ho freedom fighters believe their actions will stop terrorists, while making the establishment itself, Iron Man's team, believe they're stopping future catastrophe by coming down hard on their own people.In effect, Zemo magnifies and accelerates what was already under the surface, bringing the Avengers to conclusions that feel like logical outcomes of who they are.But Barnes is not the real terrorist, and Zemo has no plans to re-awaken the other Winter Soldiers. As complicated as the Avengers' security debate is — and as harrowing as it may be to see heroes placed at such fundamental odds — Zemo takes advantage of predictable, one-track American military heroism (the way Aldrich Killian did in Iron Man 3), a self-aggrandizing modus operandi, rooted in emotional instincts to shoot first and ask questions later.The two sides clash at a Leipzig Airport because they have each been made to believe a different terrorist narrative. They are placed predictably at odds because even their differing outlooks are merely sides to the same fundamentally violent, militaristic coin. Team Iron Man retaliates without complete information. Team Captain America fights on the false presumption of future threat. Destruction ensues.Zemo has personal motives for this mayhem: his family was killed in Sokovia during the events of Avengers: Age of Ultron. To ensure Captain America and Iron Man's fuses are lit, Zemo lures them to the isolated facility of Barnes' Siberian origin. Here, he reveals the truth that Arnim Zola hinted at in Captain America: The Winter Soldier (an admittedly blink-and-miss setup, makings the "twist" feel sudden to those not in-step with continuity). Bucky Barnes, while under the influence of H.Y.D.R.A., murdered Tony Stark's parents to prevent them from assisting American war efforts. The man Steve Rogers has been protecting was the very person responsible for Stark's deepest wounds, a truth Rogers has been aware of for years.The political specifics are stripped away by this point. Both sides have come to realize the lies that brought them here, but the personal perspectives driving them have now been magnified. Tony Stark, who has spent years trying to regain a sense of order and control, is now faced with the man who destroyed his sense of equilibrium, Bucky Barnes. Steve Rogers, who has spent the entire film doing what he thinks is right, has to both protect Barnes from what may well be righteous vengeance, and face retribution of his own, now that his unwavering moral outlook has caused irreparable harm. Stark is right, Rogers is right, and they tear each other apart.With the question of Barnes' guilt or innocence hanging in the balance — How accountable, and to whom, is a brainwashed soldier for crimes he believed righteous? — the selfishness driving each hero's ideals comes to the fore. What good is Rogers' desire to do right by Barnes when it's hurting Tony Stark? What good is Stark's newfound adherence to law when he breaks it himself?What good are these debates on security when they're being had by wounded individuals driven by selfish ideology, rather than by common good? Individuals whose sole focus is deciding on the means by which to attack, rather than the means by which to curb their violence altogether?

The Long Game

Apart from Black Widow, who's woefully short-changed after two stellar appearances, every character in Civil War gets a coherent story arc. Sam Wilson/The Falcon, a former military airman who's witnessed American governance be twisted, sides with Rogers. James Rhodes/War Machine, an Air Force recruit whose 130+ missions have prevented catastrophe, follows Stark. They each side with friends who represent their personal worldviews, despite the conflict's complicated political dimensions. And they each pay a physical price.Wanda and The Vision battle on opposing sides, despite their common and mysterious origin (the Mind Stone). Wanda, having been at the receiving end of military conflict fights to make a difference. She escapes her confines despite being held back by her guilt (Hawkeye, once again, convinces her to stand up for herself). The Vision however, knows Wanda is volatile, and claims an objective, unemotional stance in protecting people from her. He throws mathematical equations at the Avengers and calculates what decisions they ought to make "for the greater good." However, the realization of his own humanity — that his perspective is informed by emotion, and that he's prone to human error — makes him retreat from the fight. As a creation of the Avengers themselves, he is, once more, a microcosmic representation of a conclusion they must arrive at: that neither side is "objectively" right.Even newcomers Spider-Man and Black Panther receive their due. Young Peter Parker is recruited into battle by Tony Stark, and delivers a version of his uncle's "With great power comes great responsibility" line from earlier films. Where The Vision's "objectivity" is built on the false presumption of emotional distance, Parker's moral outlook is vital precisely because he's removed from the conflict. He likely doesn't know about Sokovia Accords (we see him learn about them in school in subsequent films), yet his perspective applies to either side. When you have the power to prevent catastrophe, and you don't, the resultant harm is your fault. This holds true for both warring parties, who find themselves locked in debate about what power to lean on in the first place: the power to legislate when to act, or the power to act without legislation.Black Panther on the other hand, while involved deeply in the political turmoil, turns his gaze toward personal vengeance. His mission is to kill Bucky Barnes, the man he thinks responsible for his father's death. However, he comes to his senses once he sees his vengeful quest reflected back to him — both in Zemo, whose obsession has led him to madness, and in Rogers and Stark, who descend into senseless violence over Barnes. Black Panther chooses justice instead of revenge, capturing the man responsible rather than leaving him to die.The narrative driving Civil War — Captain America and Iron Man switching places and perspectives before finally butting heads — is a payoff that could only exist in long-form storytelling. The film finally confronts the series' haphazard politics, imbuing the franchise with a new reason to be political in the first place. Marvel's muddled approach to militarism can no longer simply be a backdrop for the heroes to respond to; in stories that question the use of power, political outlook must be an extension of ethos itself, just as it is in the real world.Granted, the political perspectives here remain just as abstract as in previous films. At no time are there specific examples that parallel real-world intervention, but the film leans hard on the personal biases that often drives these decisions. Changes of heart aren't enough when they exist alongside lies and unconfronted histories. From this point on, the series begins to dramatize this need to investigate the past, in films like Thor: Ragnarok and Black Panther. Come Avengers: Endgame, the past will likely hold the key to the Avengers' future.It hurts to see your heroes fall, and it hurts that it may take a global annihilation to bring them together. Their failures in Captain America: Civil War tear them apart, revealing the fragile, paradoxical nature of even the most powerful interventionist forces, setting the stage for a dramatic reunion.The original Avengers, including Steve Rogers and Tony Stark, are among the few heroes left standing in Avengers: Infinity War. Moving forward, a question the series might need to answer, if it hopes to close its loop, is whether the Avengers will settle on a way to wield their powers responsibly.

***

Expanded from an article published April 18, 2018.