The Ending Of Better Call Saul Invokes A Literary Classic

Spoilers for "Better Call Saul" follow.

"I want to believe there's a heaven. But I can't not believe there's a hell." "Breaking Bad" creator Vince Gilligan has used this quote, cribbed from his partner Holly Rice, to explain his moral outlook. It may seem cynical on the surface, but buried within is a belief in justice. After all, the last moment of "Breaking Bad" is Walter White/Heisenberg (Bryan Cranston) falling dead as Badfinger sings, "Guess I got what I deserved."

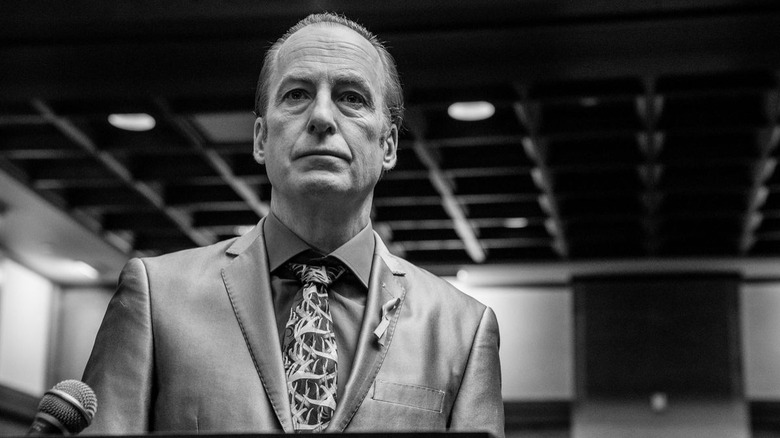

Gilligan's philosophy of justice permeates "Saul Gone," the finale of prequel/sequel "Better Call Saul" about Heisenberg's lawyer, the once-and-future Saul Goodman — real name Jimmy McGill (Bob Odenkirk). During "Saul Gone," the captured Jimmy's goal changes from escaping justice to redeeming himself in the eyes of his ex-wife Kim Wexler (Rhea Seehorn). So, he throws away the mother of all plea deals, lays his soul bare in court, and is sentenced to prison. It's not quite a happy ending, but it is a fair one. Even if Jimmy achieved personal redemption, he didn't earn the right to walk away scot-free either.

Series co-creator Peter Gould, who personally wrote and directed "Saul Gone," has said "A Christmas Carol" influenced the episode, specifically citing the "three ghosts" featured in flashbacks: Mike Ehrmantraut (Jonathan Banks), Walt, and Jimmy's brother Chuck McGill (Michael McKean). However, the closer parallel to Jimmy McGill is not Ebenezer Scrooge but Rodion Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Fyodor Dostoevsky's "Crime and Punishment." An anti-hero tormented by his actions, Raskolnikov is an ancestor of the morally grey characters who inhabit Gilligan and Gould's Albuquerque.

Crime and punishment

Born and raised in Tsarist Russia, Dostoevsky became involved with radical literary groups, including the Petrashevsky Circle. Arrested for his involvement in 1849, Dostoevsky spent four years imprisoned in Siberia and six years drafted. This experience shaped "Crime and Punishment," first serialized in the magazine "The Russian Messenger" during 1866.

"Crime and Punishment" spans many pages and an ensemble cast, but Raskolnikov is the story's soul. A poor student living in Saint Petersburg, Raskolnikov is desperate to save his sick mother Pulkheria and his sister Dunya from poverty. Thus, he decides to murder an elderly pawnbroker, Alyona Ivanovna, and rob her apartment. During the act, he's caught by her impaired sister then kills her as well. A proto-Nietzschean, Raskolnikov reasons that "extraordinary" individuals may commit such acts. He tells himself that were Napoleon in his place, he would've done the same thing, for he and the French Emperor are of the same mold. But even as Raskolnikov tries to rationalize his crime, he can't escape it.

As he walks free, he's punished by inner torment. His guilt forces him to consider his motives; did he really murder for money and his family, or just to experience the act of killing? He's also paranoid about being caught, especially once he meets the curious detective Porfiry Petrovich. However, it's not Porfiry that catches Raskolnikov, but the young man's love for a prostitute named Sonya (or Sonia, depending on the translation).

Repentance and redemption

Raskolnikov learns that Sonya was friends with the pawnbroker's sister, Lizaveta, and decides he must tell her of his crime. As he does, Sonya pushes him to confess:

"Go at once, this minute, stand at the crossroads, bow down, first kiss the earth which you have defiled and then bow down to all the world and say to all men aloud, 'I am a murderer!' Then God will send you life again ... Suffer and atone for your sins by it, that's what you must do."

And yet, she doesn't reject him:

"He looked at Sonya and felt how much of her love was on him, and, strangely, he suddenly felt it heavy and painful to be loved like that."

Raskolnikov initially refuses Sonya's pleas, saying he'll live with his burden, but he reconsiders. He almost backs out, thanks to a neighbor of the Ivanovna sisters having confessed and one Arkady Ivanovich Svidrigailov (Dunya's amoral former employer) taking knowledge of Raskolnikov's guilt to his grave. However, the sight of Sonya in the police station affirms his decision to confess.

In "Better Call Saul," during Jimmy's post "Breaking Bad" exile in Omaha as "Gene Takovic," he's looking over his shoulder and a prisoner of himself, similar to Raskolnikov. When he reaches out to Kim, she gives him the same advice Sonya gave her lover. After Jimmy's caught, he backs himself out of a corner, but then throws it away. Why? According to Odenkirk, "[Jimmy confesses] because he loves Kim, and he does it because he knows that in the long run, it's the thing that's going to show her that he was always a really good guy. And not a broken snake."

Raskolnikov and Jimmy McGill may both be cynics, but they valued love more than freedom.

Hope and endings

During his confession, Jimmy doesn't just own up to his crimes in the Heisenberg drug empire. He also finally admits to having Chuck's malpractice insurance canceled all the way back in "Better Call Saul" season 3, which helped drive his brother to suicide. Jimmy's repentance would be incomplete without his original sin, after all. The way Dostoevsky writes Raskolnikov's confession indicates similar exhaustion:

"[Raskolnikov] fairly and clearly maintained his confession, without in any way confusing himself as to the details or extenuating any circumstance. Neither did he mutilate any fact, nor spare the most minute detail."

Tried and convicted, Raskolnikov is sentenced to a labor camp in Siberia. While he's there, Sonya visits him; her love and his acceptance of his penance nurses his soul to health. Jimmy is sentenced to 86 years in maximum security prison, but is treated like a celebrity by the other inmates and gets a surprise visit from Kim. It's implied this won't be the last time she visits.

There are some differences. Raskolnikov only has to serve eight years, leaving a more hopeful ending — like Dostoevsky himself, it's likely that one day he'll eventually be a free man again, so he and Sonya can get their happy ending. Jimmy, on the other hand, is probably going to be a permanent resident of his new home. Even so, he prefers it over his Kim-less existence back in Omaha.

Acknowledging your crimes, honestly and without mitigation or justification, doesn't absolve you of punishment, but it's the only thing that can set your soul on the right track. Both Jimmy and Raskolnikov found that prison was worth it if it meant a cleansed conscience.