Why Clint Eastwood Can't Buy Into The Idea Of An 'Auteur' Director

"Auteur" is one of those words that get thrown around a lot, yet its meaning seems to vary depending on who you ask. It's a term that is most often afforded to directors whose work is held in high regard, but it can just as easily be applied to a filmmaker whose movies are rarely the bee's knees in the eyes of critics. This issue has even led to the coining of the somewhat polarizing phrase "Vulgar Auteurism" as a way for critics to avoid having to lump the Martin Scorseses of the world in with the likes of Michael Bay and Roland Emmerich.

In truth, you could fairly describe all three of those directors as being "auteurs." The basic idea dates back to at least 1954 when François Truffaut coined the term "La Politique des Auteurs" or "The Policy of the Authors." Even then, Truffaut was building on the writing of critics like André Bazin, who observed that certain directors have motifs both aesthetic and thematic that show up in their work time and time again, to the degree it makes them the closest thing that their films have to an "author."

The obvious counter-argument to this suggestion is that film is simply far too collaborative an art form for any one person to claim a movie as theirs and theirs alone. Such is the stance favored by Clint Eastwood, a fella who might very well give me his signature squint and scowl if I were to point out he could readily be labeled an auteur himself (which, dear reader, I'm totally going to anyway).

Eastwood wasn't an auteur at first

Director Joe Russo recently got read the riot act online for claiming auteur filmmaking "was conceived in the '70s" in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter. While there are plenty of reasons to take the mickey out of Russo (don't worry, he can handle it), one can also see what he was trying to get at here. Contrary to Russo's statement, "auteurism" is a thing that's observed rather than practiced. Even so, there was a notable influx of directors in the 1970s who enjoyed great success making personal, idiosyncratic films, be they "Star Wars" or "Taxi Driver."

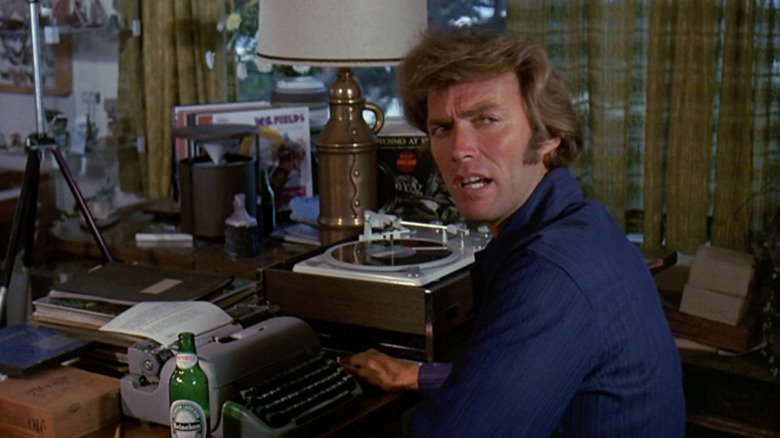

Similarly, the '70s saw Eastwood make the leap from actor to actor/director, starting with the 1971 thriller "Play Misty for Me." More of a workman director than an auteur at first, Eastwood began to amass a group of creatives he would work with over and over, steadily promoting those who started out lower on the ladder to higher-ranked positions on his crew. Naturally, not everyone who got bumped up thrived in their new roles, but Eastwood never let that stop him.

He explained his reasoning in a 2006 interview for DGA Quarterly:

"If people want to progress to another division and they have the ambition, they should be allowed to fulfill their ambitions. Just like when I had the ambition to become a director. I work with a lot of people who started out as assistants. [Editor] Joel Cox started out in the mailroom. As you work with people over and over, you come to know what to expect. If you have a new person come on, that's an unknown factor. Maybe it turns out to be a great surprise. Or you can get surprised the other way. But after a while, you get comfortable."

The truth about auteurism

Eastwood continued, citing the collaborative nature of film as the reason he doesn't buy into auteurism:

"A lot goes into making a film. I know a lot of cineastes only think of the director, the auteur theory and all that. But it's a whole group, a company, that makes a movie, and it's a company that works only as well as its weakest link. I try to get the enthusiasm of everybody–that's been my best trick, if I have a best trick. I try to get everybody involved. If the janitor can come up with a great idea for a shot, that's fine with me. There're no proprietary interests. I try to keep my ego and everybody else's ego out of it."

The thing Eastwood and, for that matter, a lot of people seem to misunderstand about being an auteur is it doesn't, per se, refer to a director who rigidly controls every aspect of a film. It refers to one whose body of work illuminates their concerns and preoccupations as storytellers.

If Eastwood wasn't an auteur by the time he made his touchstone Western "Unforgiven" in 1992, he definitely was after that. For the rest of the '90s, Eastwood maintained a consistent style (un-flashy, ruminative) and set of interests (regret, mortality) in films varying as wildly in their plots as the romance "The Bridges of Madison County" to the rascally-old-timers-in-space dramedy "Space Cowboys." There's no mistaking his output in the 21st century either, from their color-drained visuals and unhurried pacing to their rejection of machismo and their questioning of figures in positions of power and authority.

Eastwood isn't wrong: every film is a group effort. But they can also be in service of a singular, guiding vision, as his work has been for decades.