Patton Ending Explained: That All Glory Is Fleeting

How do you fit all the complexities of a person's life into the space of a feature film? The short answer is you don't, which is why I've always found the biopic the most unsatisfying of genres. "Patton" avoids many of the usual pitfalls by limiting its scope to the three-year period during World War II which are central to General George S. Patton's enigmatic legend as a vainglorious, troublesome figure who also happened to be a tactical genius on the battlefield. The result is a three-hour character study that really feels like we get inside his head; while there are several huge battle scenes, all the real action is in George C. Scott's magnificent performance, who embodies the General so naturally that it hardly seems like he's acting at all. If director Franklin J. Schaffner wanted to save some money, he could have scrapped the battles altogether and just let us watch them play out on the actor's face instead, which might have been even more interesting.

Aside from a few other key figures, Patton is the sole focus point among a cast of hundreds, an aggrandizing approach that is fitting for a man who felt it was his destiny to lead many troops in battle and feared the conflict would end before he could make his mark. With barely a hint of his personal life or history prior to the war, Schaffner presents a towering figure who loved battle above all else. Similarly, the film ends just before Patton's death in 1945 and doesn't even mention it; for all uninformed audience members knew back in 1970 when it was released, Patton might have still been alive. Yet that choice is in keeping with some of the major themes of Schaffner's epic, so let's dig into it.

So what happens in Patton again?

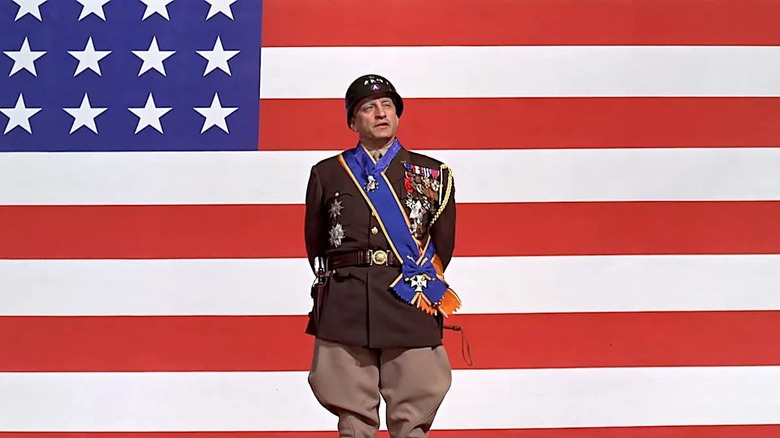

"Patton" opens with its most famous scene: The frame is filled with the Stars and Stripes as the helmeted figure of George S. Patton (Scott) takes the stage, delivers a grandstanding motivational speech, and walks away.

Next, we're in North Africa. Patton takes command of a beleaguered tank corps that has recently suffered a humbling defeat by the Desert Fox, General Erwin Rommel. Patton quickly whips them into shape and, with British General Bernard Montgomery pressing from the east, masterminds a vital victory at El Guettar in Tunisia.

Triumphant in Africa, Patton and Montgomery turn their attention to Sicily, the key to invading Italy and securing an Allied foothold in southern Europe. Patton's ambitious plan is turned down in favor of a more cautious approach, ordered to protect Montgomery's flank as they advance on the port city of Messina. "Old Blood and Guts" disobeys the directive, bypassing much of the heaviest fighting and sweeping in via the capital Palermo instead, much to the annoyance of General Bradley (Karl Malden).

Patton's bold move is a tactical success, but he tarnishes his victory by striking a traumatized soldier who he dismisses as a coward. The incident scuppers his opportunity to command the American forces as they prepare for D-Day, with the post given to the more balanced Bradley instead. Patton is sidelined in England for the Normandy landings and used as a decoy instead, but he gets a reprieve when Bradley puts him in charge of the Third Army in France. Seizing his chance, Patton's troops make great gains and ride to the rescue of an Airborne Division under siege in Bastogne. Yet once again, Patton's big mouth deprives him of the glory he craves so desperately.

Does Patton still hold up?

I found it a bit weird watching "Patton" from a modern perspective. Most war movies of the past 50 years have been of the anti-war variety, and I was surprised to see a film released while the Vietnam war was still ongoing to take such a reverent view of a "screwball old horse cavalryman" like Patton. Released the same year as "Catch-22," the patchy adaptation of Joseph Heller's famous anti-war satire, Schaffner's film is nostalgic about old-fashioned warfare where two Generals would slug it out on a battlefield with two huge armies at their disposal. While Francis Ford Coppola and Edmund H. North's screenplay doesn't shy away from Patton's faults, it almost turns him into an underdog in the second half of the film.

It's also worth considering Scott's performance as Patton in comparison with his earlier General in "Dr. Strangelove," the gum-chomping Buck Turgidson. Patton may have been willing to lay down the lives of thousands of men to secure a victory, but he did so with a very real sense of the human cost and the operational nous to carry it out without needlessly sacrificing his troops. Turgidson, on the other hand, is of an era dominated by the "wonder weapons" mentioned darkly towards the end of "Patton." Distanced by technology, he makes decisions without any reasonable perspective or restraint and is completely gung-ho about the prospect of 10 to 20 million civilians dead in his fantasy of a winnable nuclear war.

Released just eight years after the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world to the brink of nuclear annihilation, and with the chaotic disaster of Vietnam still unfolding, maybe it's not such a surprise that "Patton" is a little misty-eyed for the old days of military beasts like Patton, Rommel, and Montgomery.

Destiny and reincarnation

The excellent screenplay leans into the idea that Patton was an anachronism in an age of modern warfare yet a military scholar more well-read than any of his peers or adversaries, able to pick from the playbooks of Caesar, Hannibal, and Napoleon. Or even Erwin Rommel while fighting against him. True to his real-life counterpart, Scott's old-school campaigner believes greatness is his destiny and talks about capturing or killing thousands of German soldiers as if he did it personally, using his army as a sword.

Another complexity that the screenplay skilfully delves into is that Patton was a devout Christian who also believed in reincarnation, adding another layer of mystique to an already outsized character. This element is beautifully handled throughout the film, not least in the spine-tingling scene where he visits the ancient battlefield at Carthage and says with hushed certainty: "Two thousand years ago. I was here." Jerry Goldsmith's remarkable score really helps emphasize this theme here, repeating an eerie fading trumpet motif while Patton muses on reincarnation, as if calling to him across the centuries from past lives.

Patton died from injuries sustained in a car accident rather than the glorious death in battle he pictured for himself. Something of his passion for conflict lived on in the character of Colonel Kilgore in "Apocalypse Now," although Schaffer and Coppola's version of the General is a far more well-rounded and admirable figure. Much of that is down to Scott's portrayal. You have to wonder if a little of Patton's spirit found its way into the actor with this kind of performance, for which he deservedly won an Oscar

That all glory is fleeting

"Patton" ends as the General is relieved of his command after comparing American politics to Nazism. As he leaves his opulent digs, he's met by Bradley, who offers a few consolatory words. As they walk and talk, Bradley narrowly saves Patton by pushing him out of the way of a runaway oxcart, causing Patton to suggest that the only proper way for a man like himself to die is "by the last bullet in the last battle of the last war."

Bradley predicts that in the future "just being a good soldier won't mean a thing," and watches wistfully as Patton walks away into the distance with his dog. We hear Scott's voice:

"For over a thousand years, Roman conquerors returning from the wars enjoyed the honor of a triumph, a tumultuous parade. In the procession came trumpeters and musicians and strange animals from the conquered territories, together with carts lad with treasure and captured armaments. The conqueror rode in a triumphal chariot, the dazed prisoners walking in chains before him. Sometimes his children, robed in white, stood with him in the chariot or rode the trace horses. A slave stood behind the conqueror holding a golden crown, and whispering in his ear a warning: That all glory is fleeting."

With his extensive knowledge of military history, Patton knew more than most that empires fall and victors are always brought low; his final words are not just an elegy for his own career, but for the style of warfare that he loved so much. As the credits roll and the trumpet calls again, Coppola and Schaffner decide not to even mention Patton's death. Instead, they let him walk away into history and immortality, perhaps in readiness for his next incarnation.