Robin Williams Went All In For His Moscow On The Hudson Role

By the early 1980s, Hollywood thought it had Robin Williams pegged. Based on four mostly successful seasons of "Mork & Mindy" and two explosively funny HBO specials ("Off the Wall" and "An Evening with Robin Williams), he was a whirling dervish of hilarity who existed to light up your living room. He was easily one of the best, most agile-minded comedians on the planet, but his talent was specialized. If you wanted to hear Elmer Fudd sing Bruce Springsteen's "Fire," Robin Williams was your man. No one wanted to see him straitjacketed in a dramatic role.

Paul Mazursky believed otherwise. Though the writer-director of comedic character studies originally conceived of "Moscow on the Hudson" as a star vehicle for ballet dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov, who was to play a Russian ballet dancer who defects during a stop in New York City, he quickly adjusted the screenplay for Williams when Misha passed. Now the character of Vladimir Ivanoff was a saxophonist traveling with a Moscow circus. When he was cast, Williams couldn't speak Russian or play the saxophone — which wasn't a huge deal because you can get by simply speaking the text on the page and faking the sax performance via careful editing. Mazursky was about to learn what Hollywood didn't quite get yet: Robin Williams was a full-blown genius.

A crash course in Russian and saxophone

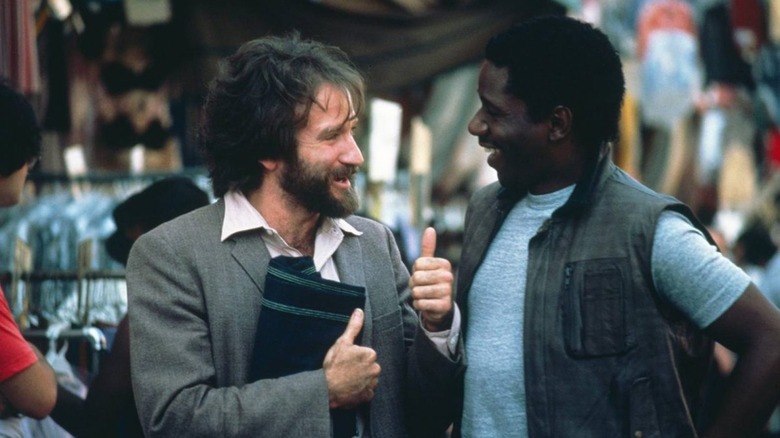

Williams wasn't satisfied with mere mimicry. According to Dave Itzkoff's biography "Robin," when he landed the role of Vladimir, he immediately grew out his hair and beard, and took Russian lessons. When the film shot in Munich (which doubled for Moscow), it was important to him to be able to mingle convincingly amongst Europeans. It was here that he discovered his accent needed a little work. Per Williams, "They said I sounded Czech. I sounded Polish. I sounded Georgian. A lot of Russians see the film and go, 'Who iz ze Polish boy in ze lead?'"

The saxophone playing went much better, which is amazing because, outside of goofing around on the harmonica, Williams had never played a musical instrument in his entire life. Prior to shooting, Greg Phillips taught him the basics. Williams then practiced for hours a day, and, in a limited period of time, proved shockingly adept. Phillips was astonished, particularly because Williams couldn't read a note of sheet music.

"Even though I insisted that he learned to read music," he said, "his mind was so fast that we would—I thought—be reading a piece, and he would memorize it as quickly as we had played through it. So then, when I would say to Robin, why don't we go back to Bar 15 or 16, he would go, 'Uh, yeah, where's that?' Because he had it in his head, but he couldn't tell on the music where it was."

The boundless, deeply missed genius of Robin Williams

Itzkoff's book repeatedly holds that Williams possessed a photographic memory. This doesn't quite explain how he learned to convincingly play Billy Strayhorn's "Take the A-Train" in such a condensed period of study, but it adds up in that his genius seemed boundless. There seemed to be nothing Williams couldn't do.

"Moscow on the Hudson" was a modest box office success, one that Williams desperately needed after the less-than-stellar commercial performances of "The World According to Garp" and "The Survivors." Most importantly, he received his best reviews as an actor, suggesting that his big-screen potential had yet to be adequately tapped. Even then, no one really understood the extent of his brilliance. Mazursky's film gave us a taste. The best was yet to come.