Cool Hand Luke Ending Explained: A Failure To Communicate

If you're a law-abiding citizen with no experience of life behind bars, a good prison movie is a window into a harsh world far removed from regular day-to-day life. There is something so intense about the idea of incarceration that makes it great for drama, and also lends itself to symbolism and metaphor beyond the usual narrative beats of violent inmates, old lags, sadistic screws, and suspenseful escapes.

I recently had a discussion around this with a friend regarding "The Shawshank Redemption." He keeps his kids well away from any screen violence while I have watched the movie with my seven-year-old daughter. Why, he wanted to know, did I think a film containing brutal beatings, suicide, and sexual assault was suitable for her? Well, we skipped some of the darker stuff, and I felt the story's overall message of resilience, hope, and friendship was the important thing, reflected in how its positive themes have won a place in the hearts of people all over the world.

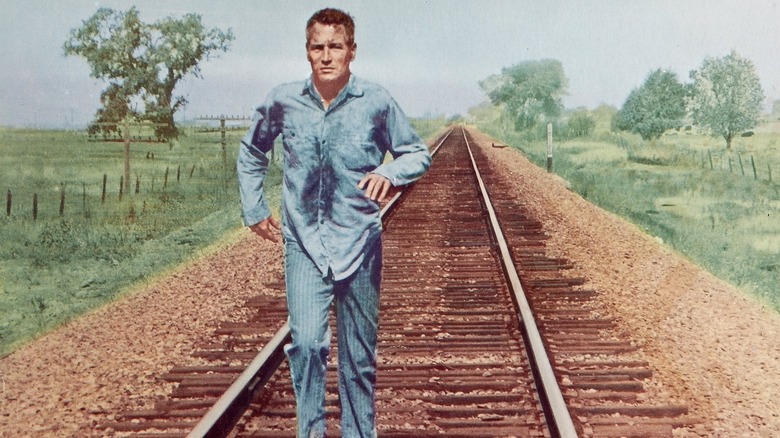

Another prison movie that is right up there on the entertainment scale while also packing plenty of deeper messages is "Cool Hand Luke," the '60s classic starring Paul Newman at the height of his powers. The film provided one of his signature roles and his performance garnered his fourth Oscar nomination for Best Actor (after "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof," "Hud," and "The Hustler"). His role as the rebellious Luke Jackson is one of the great anti-authoritarian figures of American cinema, standing alongside Jack Nicholson's Randall Patrick McMurphy in "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest."

While the bittersweet ending may seem straightforward, there is plenty to unpack to get the most out of it.

So what happens in Cool Hand Luke again?

One drunken night out, World War II veteran Luke Jackson (Paul Newman) indulges in a spot of vandalism, cutting the heads off a row of parking meters. The stunt lands him with a two-year stint on a chain gang. The prison is run with strict discipline by The Captain (Strother Martin), and even a minor infringement means a night "in the box." To make sure nobody gets any ideas about escaping, The Captain's right-hand man is Walking Boss Godfrey (Morgan Woodward), a menacing rifleman whose mirrored shades have earned the moniker "The man with no eyes."

Luke initially butts heads with the burly top dog inmate, Dragline (George Kennedy), resulting in a boxing match to settle their differences. Despite being no match for the big man's strength, Luke just won't give up. His resilience wins the respect of Dragline and the other prisoners, and he cements his legendary status by winning a game of poker with a "handful of nothing," prompting Dragline to give him the nickname "Cool Hand Luke."

Luke's antics and disrespect for the prison authorities lift the other inmates' spirits, but his mood sours when his mother passes away and he is put in solitary confinement to prevent him from breaking out to attend her funeral. This makes him more determined than ever, but he is recaptured after each escape attempt. The Captain tries breaking him with harsh punishment and, when it appears he has succeeded, the other prisoners lose faith in Luke. But has The Captain really subdued Luke's fighting spirit?

Two great cinematic rebels

"One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" and "Cool Hand Luke," novels by Ken Kesey and Donn Pearce respectively, both centered on charismatic wild cards throwing themselves defiantly against the system. Kesey's book, published in 1962, anticipated the social struggles that would intensify as the decade wore on by pitting McMurphy against "The Combine," the monstrous mechanism that controls society and represented by Nurse Ratched, the cruel head nurse and "The Man" of the story.

Pearce's novel arrived three years later but its movie adaptation beat "Cuckoo's Nest" to the screen by eight years, under rather unusual circumstances. Kirk Douglas bought the rights to Kesey's novel and starred in a failed Broadway version before deciding to produce a film version. To direct, he picked an up-and-coming star of the Czech New Wave, Milos Forman. Forman never received the promised screenplay, which he suspected was confiscated by the strict censors of Communist Czechoslovakia.

This incident was symptomatic of the times; during a period of great social and political upheaval, non-conformity was becoming an increasingly powerful weapon against the authorities, and not just in America. While the States witnessed the Civil Rights movement, race riots, and anti-Vietnam war protests, rebellions and uprisings flared up in many other countries. Hong Kong was rocked by riots in '67, while '68 saw civil unrest in France and the ill-fated Prague Spring in Forman's home country.

If it wasn't for the Czechoslovak censors, Luke and McMurphy might have stood side by side as two of cinema's great non-conformists at a time when they were needed most. As it played out, they bookended some of the most tumultuous years of the period, with "Cuckoo's Nest" serving as an elegy in the Post-Watergate, Post-Vietnam '70s.

Non-comformity as an act of resistance

How do you fight back against The Man when The Man holds all the power? Nonconformity requires courage, willpower, and tremendous personal belief, and not everyone has the stomach for that kind of battle. Luke, embodied so wonderfully by Paul Newman, has clearly had that anti-authoritarian streak his whole life, summed up by the futile act of vandalism that gets him imprisoned in the first place.

It's not just the authority of The Captain that Luke resists. He initially refuses to observe Dragline's status among his fellow inmates, resulting in the boxing match. Foreshadowing the greater fight against the warden and his guards who hold all the power (guns, dogs, chains, fences), Luke is severely outmatched by Dragline in terms of size and strength, but he keeps going anyway. The subsequent poker game, when Luke wins with crap cards, is also key. He becomes an underdog who might succeed against all the odds, despite holding a handful of nothing.

Like McMurphy, battling the system eventually proves fatal for Luke, but he becomes a hero and a galvanizing force in the eyes of his fellow inmates. The guys on McMurphy's ward grow enough balls to openly disrespect Nurse Ratched, whose hold over them has gone. Dragline attacks Godfrey, knocking off his mirrored shades and leaving him scrambling pathetically in the mud. It's a small but significant act of retaliation from Dragline, who reclaims his Top Dog status not just by his strength and authority, but because he was Luke's friend and keeps his spirit alive through recounting the tale to the boys back in the chain gang.

A failure to communicate

The Captain likes to talk about how he's a reasonable man but the conversation only goes one way, as demonstrated by his "failure to communicate" speech. He's not interested in communicating at all and will punish anyone who doesn't obey his rules to the letter. Similarly, Godfrey's eye contact only goes one way, with his peepers hidden behind his mirrored shades. If the eyes are windows to the soul, it is his intent to convince the inmates he hasn't got one, making him a much-feared enforcer of almost mythic proportions.

The parallels with current events at the time are clear. If the Captain, talking like a folksy politician, represents the government, then Godfrey stands for the police, whose brutality helped spark many race riots in the '60s. High-profile assassinations were rife at the time, with the murders of JFK, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and RFK. In this context, Luke represents the dissenting voice that is silenced with a bullet. By the time we come to the final standoff in the church, it is clear that The Captain and his men are just looking for an excuse to take him down; there will be no communication, no negotiation at this late stage. Instead, Luke's final act of defiance, mocking The Captain, is met with a fatal shot from Godfrey's rifle, ending the one-sided conversation.

If there is any doubt that it is anything but an assassination, we overhear The Captain saying he will take Luke back to the prison hospital rather than a much closer regular hospital, obviously planning to let Luke bleed out rather than allowing him to disrupt the other inmates any further. But it is a futile act; Luke lives on in their memory and becomes a martyr.

Martyrdom and Christian Imagery

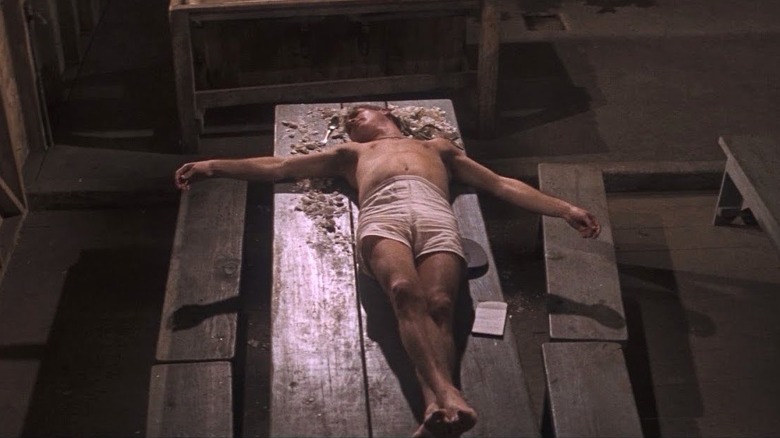

"Cool Hand Luke" is loaded with Christian imagery and symbolism, and you don't need to be a particularly religious person to pick up some of the bigger ones. The most obvious is the repeated motif of the Cross. After Luke completes his bet of eating 50 hardboiled eggs in an hour, he is left lying exhausted on a table in the pose of Jesus on the crucifix, arms spread and feet crossed, with eggshells around his head resembling a crown of thorns. At the end of the film, the imagery is repeated as we see a photo of Luke with some good-time girls, once ripped to pieces but now taped back together, superimposed over a long shot of a crossroads. The mended rips also form a cross, just in case we missed it.

Luke is set up as a redeemer for the other inmates, and he is punished beyond proportion for all their sins. The scene where he is forced to dig a hole, fill it in, and dig all over again echoes Christ's ordeal carrying his own cross to his crucifixion. In the closing moments, Dragline becomes a Judas-like figure, delivering Luke to his captors and his fate. Ultimately, Luke dies fighting the power and becomes a martyr, his spirit and sense of rebellion living on in the reverent tales of the other prisoners.

"Cool Hand Luke" is an effortlessly enjoyable movie, but all these details make it all the more resonant if you're looking for a deeper reading. I've watched the film several times, but I never feel sad when Luke is carried away at the end. He dies with a smile on his face, satisfied that he has fulfilled his destiny: Sticking it to The Man.