Spirited Away Ending Explained: On Earth As It Is In Ghibli

Like any other movie, the first impression of Hayao Miyazaki's "Spirited Away" comes from its title, which, in this case, is the simplified English version of the original Japanese title Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi. "Sen" and "Chihiro" refer to the two given names of the film's young protagonist — emphasis on "given," since her parents and boss hand them to her with her fate from moment to moment.

The movie becomes a bathhouse crucible for forging Chihiro's character: instilling the value of hard work and the perils of greed and forgetting oneself in the struggle to make ends meet or achieve financial success. "Sen," in fact, is the Japanese word for "thousand," with the lowest denomination of bills in Japanese currency being the 1,000-yen note.

At the same time, work is a means to an end; its broader purpose serves to help Chihiro grow up and acquire the skills and life experience necessary to make her own way in the world. That it's a kami or "spirit" world is incidental. Strip away all the colorful creatures, and "Spirited Away" and its bathhouse (inspired by a real onsen on Shikoku) looks very much like a microcosm of the real world.

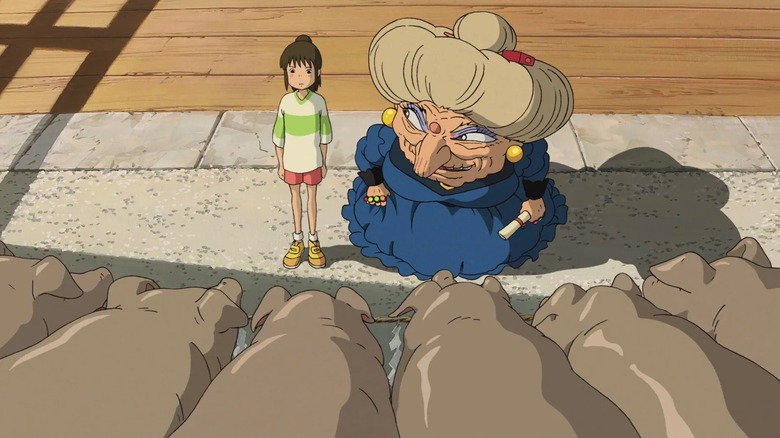

The title's other key word, kamikakushi, links Chihiro's story to legends in Japanese folklore where a person might disappear or die, thereby being "spirited away," if their actions or attitude put them in disfavor with the gods. The spoiled child Chihiro signs a contract with the sorceress Yubaba and enters indentured servitude in the bathhouse to learn a life lesson.

Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi might be a mouthful if you don't speak Japanese, but it gives a fuller picture of what "Spirited Away" and its ending are all about. Spoilers follow.

Alone with No-Face

Miyazaki has said that, for him, what "constitutes the end of ['Spirited Away'] is the scene in which Chihiro takes the train all by herself." Technically, she's not alone, as she's sitting next to No-Face, the uninvited bathhouse customer who became a monster, eating everything and everyone in his path.

At one point in "Spirited Away," No-Face is described as "the richest man in the whole wide world." He takes more bath tokens than he needs, and the bathhouse workers clamor for his gold, while Yubaba observes of them, "Your greed attracted quite a guest."

No-Face represents the insatiable hunger of capitalism, a concept introduced early in the film when Chihiro and her parents first arrive in the spirit realm on the other side of a mysterious, temple-like gate. "It's an abandoned theme park," her father declares of the world inside the gate. "They built lots of them back in the nineties. But then they went bust when the economy tanked."

This is a reference to the economic bubble bursting in Japan in 1992, less than a decade before Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli made "Spirited Away." In the first of its 12-part "Defining the Hesei Era" series, The Japan Times summed up the bubble era with a single word: excess. It was a time when consumerism ran rampant and people, as Miyazaki put it, "turned into pigs."

"Spirited Away" literalizes this transformation with Chihiro's parents, as her father follows his nose to an unattended restaurant and immediately begins filling his plate and gorging himself on food. "Don't worry, your father's here," he tells Chihiro. "I've got credit cards and cash." As if that will solve everything. For her part, Chihiro rejects No-Face and his offers of gold, telling him, "You can't give me what I want."

Free the dragon

Also on the train with Chihiro and No-Face (who is only tagging along and has regurgitated everything he's eaten by now) is the mouse form of Bo, an overgrown "butterball" of a baby who was previously afraid that contact with the outside world would make him sick. Before Yubaba's twin sister, Zenibaba, turned Bo into a mouse, he only wanted Chihiro to stay in his room and play with him under comfy cushions.

In the same way that Chihiro clung to her mother's arm, not wanting to be left alone outside the tunnel at the beginning of "Spirited Away," Bo now clings to Chihiro. He can be seen as her hyper-infantilized foil as she becomes more mature and self-sufficient, determined to deal with important worldly affairs like saving her "dragon boyfriend" Haku.

This is what sends Chihiro and company on the train to Swamp Bottom in the third act of "Spirited Away." She's come a long way from when we first met her, lounging in the backseat of her parents' car, completely at the mercy of her father's driving. Now, she's the one leading the mission to return a hanko stamp that Haku stole from Zeniba while he was under Yubaba's control.

Haku shows up in his dragon form and gives Chihiro a ride back to the bathhouse. On the way, she recalls a forgotten childhood incident her mother told her about: "Once when I was little, I fell in a river. Now it's built over. It flows underground."

This harkens back to what Zenibaba said about how "everything that happens stays inside of you even if you can't remember it." The river's name, Chihiro realizes, was Kohaku; it is Haku's real name and holds the power to free him from Yubaba's service.

'Wait, what do I do...?'

By the end of "Spirited Away," even Bo has learned to stand on his own two feet, much to Yubaba's surprise. Chihiro, meanwhile, has come of age, or perhaps just looked within to find the old soul she always possessed.

She was initially afraid to be abandoned by her parents, and in their absence, she soon latched onto Haku and relied on him to be her guide. He helped keep her from fading away when she turned intangible and was in danger of becoming a ghost. He hid her in the hydrangeas outside the bathhouse and sent her down to the lowest levels, where she met her first job reference, the six-armed Kamaji, a self-described "slave to the boilers."

Kamaji has a legion of susuwatari, or soot sprites, serving him. They carry coal for the furnace over their heads, and when Chihiro picks up a smooshed piece, she's left stuck holding it. "Wait, what do I do with this?" she asks.

It's a moment that evokes the uncertainty of being thrust into any new job or unfamiliar set of surroundings, left to sink or swim without knowing how it all works. Chihiro does have help; there's also her senpai Lin, who calls her a klutz and schools her in the ways of sir and ma'am, please and thank you. But at a certain point, Chihiro has to fend for herself and learn responsibility through grunt work, like preparing the bath for a stink spirit, which turns out to be a polluted river guardian.

Many of us go through a similar journey to adulthood (minus the stink spirit) as we strike out on our own, start paying bills independently, and maybe come to appreciate more what our parents went through to provide for us.

'It will be hard work'

At the 2001 European premiere of "Spirited Away," Miyazaki spoke of resisting logic in his creative process, instead digging "deep into the well of [his] subconscious" to conjure an imaginative animated world. This involved storyboarding before the script was finalized and then letting the plot and characters develop on their own, leading him to a conclusion that was not pre-planned, though certain elements of it — like the featureless seascape outside the train, which keeps the focus on Chihiro's first interior ride "alone" — fell into place perfectly, as if the intent was there all along.

Like the tenacious Miyazaki, Chihiro learns to trust her intuition, which allows her to recognize that none of the pigs are her parents when Yubaba presents her with a lineup of them as a final test. The ending of "Spirited Away" and indeed the whole cinematic experience of it engages the viewer on a similar level, allowing them to retroactively derive meaning from parts of this strange, phantasmagorical narrative, the way Miyazaki himself did.

This is not a movie of one idea, but many, such that it can support different interpretations or just be enjoyed as a fantasy steeped in Japanese folklore. As alluded, "Spirited Away" also touches on environmental concerns, but there's enough in it to support the argument that this is a movie about finding or rediscovering and retaining one's identity amid distractions and duties — which could apply to school just as much as work.

Neither of those things are the be-all, end-all of existence, but they both give purpose. "It will be hard work," Haku warns Chihiro, "but you'll be able to stay here," and he could just as easily be preparing a child for their time on earth as opposed to the spirit realm.