Found Footage Horror Movies The Average Person Would Never Survive

Since its inception with "Cannibal Holocaust," the found footage horror genre has largely featured two main ideas: trespassing, and a fascination with times past. Its characters, whether filming a documentary, capturing memories, or investigating a regional legend, spend most of these movies marching right into a space they've got no business entering, failing to heed warnings, and ultimately underestimating whatever malevolence they disturb. As a result of the trope, the average horror-savvy fan can avoid trouble simply by avoiding the Old Bad Place. Don't want to meet the Blair Witch? Steer clear of the Burkittsville woods. Enjoying the world of the living? Maybe don't set up your Halloween haunt in a hotel known for being aggressively haunted. Collingwood Psychiatric Hospital literally had "Death awaits" sprayed on its chained doors, but that didn't stop the ghost-hunters of "Grave Encounters" from bringing a boom mic to their own collective slaughter, nor did it keep a second crew from strolling to their doom in the sequel.

It brings moviegoers comfort to know that most of these shaky-cam terrors can be evaded as long as they don't trespass into forbidden areas, but there are some found footage movies that are impossible to survive, no matter where one treads. Several of these movies still have a breach of some sort: The camera crew of "REC," for example, willingly goes to a building holding rabidly infected tenants, though they're only supposed to be filming a TV segment and don't know the true nature of the emergency they're called to. But the following films would be pretty insurmountable for the ordinary person if they found themselves stuck in each movie's respective situation. Here are five found footage horror movies the average person would never survive.

Paranormal Activity (2007)

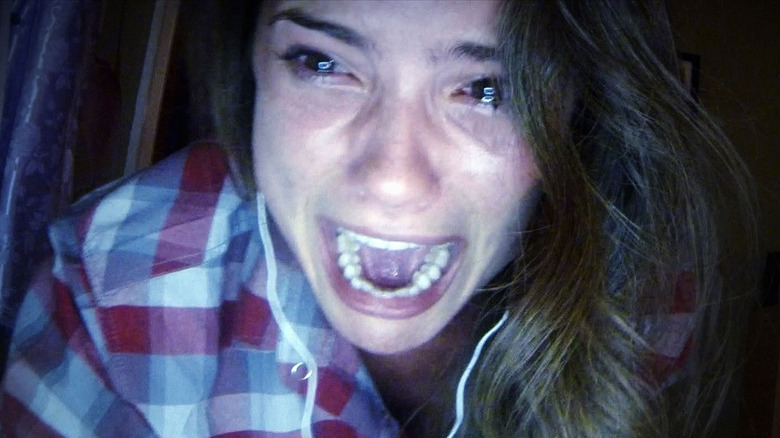

First up is an early-aughts gem that ushered in fistfuls of sequels, prequels, spin-offs, and imitators. Despite its shoestring budget (and partially because of it), Oren Peli's debut feature became one of the most profitable horror movies of all time due to its economic but effective scares. "Paranormal Activity" is a story about a young couple who set up a camera to capture proof of a supernatural presence in their San Diego home, which is all fun and games until Katie (Katie Featherston) starts going into trances and gets a nasty bite mark from their spooky roommate.

The threat isn't so much about the location as it is about being caught in the crosshairs of a demon — one that has been breathing down Katie's neck since her childhood, but has now redoubled its efforts to come after her. The entity is presented peripherally through hoof prints, shadows, and bumps in the night, and once it chooses who it wants, the demonic presence ratchets up the fear factor and feeds off of its target's misery until possession becomes inevitable. The negative energy in the house becomes overwhelming, especially to the only outsiders who could possibly intervene; even the demonologist called by the couple won't venture into the house for long before he gets that old "Amityville Horror" urge to vacate the premises, post haste. No amount of positive affirmations and white sage smudging will save you from being overtaken. If you happened to find yourself in this situation, not only would you not survive, but your loved ones wouldn't make it out of the house, either.

REC (2007)

This 2007 Spanish film features a film crew of two tagging along with firemen on an emergency call to a Barcelona apartment building full of ordinary folks -– along with Patient Zero for a deadly infection. A police officer approaches, a screaming old woman attacks him, and it's off to the races. The impossible-to-survive part of "REC" isn't so much the old woman or the cop, who now has about 25% less neck than before. Once some characters make the decision to immediately leave (a rare move in a horror film, but too late for these poor souls), they find the doors sealed by the health authorities. The movie's American remake, "Quarantine," ups the ante with trained snipers posted outside the building, who put a bullet in one escapee. Like Martha and the Vandellas sang, these people of Rambla de Catalunya have got nowhere to run to, baby, nowhere to hide.

The situation worsens: TV and landline phones are down, there's no cellular reception, and they are effectively cut off from the outside world. Despite the building being filled with people who are familiar with its layout and probably know all the good hiding spots, the final tally is sixteen kills/infections within the film's 78 minute runtime, at an average of one victim nearly every five minutes. The movie's long unbroken takes capture the speedy infection rate, often catching its victims off guard amid the confusion. Considering the amount of people in the real world who will call a deadly virus a hoax even as it destroys their bodies, stopping or even slowing this spread would be impossible. All parties involved would, as the kids say, get REC'd.

The Bay (2012)

This found footage horror movie also happens to be an eco-horror picture, with its footage purported to be confiscated by the American government in an effort to suppress knowledge of a man-made crisis. "The Bay" director Barry Levinson originally aimed to make a documentary about pollution in Chesapeake Bay forming a marine dead zone, where waste runoff and over-harvesting of oysters (Mother Nature's water filters) depletes the amount of oxygen in the water. With little oxygen, no marine life, and climate change exacerbating the whole situation, the institutional response is predictably underwhelming — an element that lends itself well to environmental horror. Levinson's research veered into a fictional narrative instead, but the filmmaker claims 80% of it is "backed up with factual information."

Chronicled via cell phone footage, news reports, and dashcams, "The Bay" focuses on a seaside Bay town beset by man-eating isopods, the result of chicken excrement from the local farming industry getting into the water along with other toxins. The entire town falls ill with boils and lesions, with many complaining that they can feel bug-like movement under their skin. Their mayor takes on the supervillain role seen in the Amity Island mayor in "Jaws" -– namely, prioritizing local economy over citizens' safety and dismissing the problem until bodies pile up — and by then, everyone has already touched the water in some fashion.

But where "Jaws" makes its moviegoers afraid to go into the water, "The Bay" brings the party ashore and makes you think twice about eating the seafood or frolicking in the sprinklers. Levinson's mockumentary approach and substantial research brings a sobering realism to the events; just as the last two years have proven, many Americans are too busy living their lives to address a health crisis until it's sadly too late.

Unfriended (2014)

There is trespassing in Leo Gabriadze's tech-centric "Unfriended," if you really want to split hairs about it. It's just that the line crossed is a moral one; the trick to avoiding the wrath of this particular evil is to never participate in cyberbullying, not even peripherally.

The first feature film in which the action takes place entirely on a computer screen, "Unfriended" unfolds as each tab and window opened is another avenue for terror as a group of high school friends in a Skype convo are interrupted by their dead classmate. A group of teens, who bullied their classmate to her death a year before, are gathered online when a troll with the username "billie227" reveals intimate knowledge of each person, kicking off an "And Then There Were None" situation in which each kid is compelled to fatally injure themselves. Google searches, YouTube clips, direct messaging, and video chats all carry the action forward as a supernatural retribution plays out on-screen.

While the answer to an average person surviving this scenario seems simple -– just log off and go about the day, as some characters here even urge each other to do -– "Unfriended" understands modern cyber-dependence, and the urge to engage with potential threats because they're so removed (by that little glowing screen) from any real sense of danger. As film critic Mark Kermode put it in his review, below the teen slasher-esque structure "is a film about the fact that cyberbullying only works if you partake in it, if you cooperate with it." By the time the curiosity wears away and everyone wants to log off, it becomes deadly to do so. Once caught in this cyber-hell, no one escapes alive.

V/H/S/2 (2013) segment A Ride in the Park

The coolest segment of this "V/H/S" anthology sequel is Timo Tjahjanto's "Safe Haven," and while it fits the criteria for this list, that balls-to-the-wall cult bloodbath is much like "WNUF Halloween Special" or "Chernobyl Diaries," where the victims go out of their way to travel to and flirt with a known shady area. But "A Ride in the Park," on the other hand, follows an average person through what appears to be a local area -– one that happens to be at the epicenter of a rural zombie outbreak. The segment is directed by "Blair Witch Project" co-director Eduardo Sánchez and its producer, Gregg Hale. But where the 1999 indie film makes the ordinary or curious into a terrifying environment (snapping twigs, rock piles, etc.), "A Ride in the Park" substitutes urgency for dread. Starting with a bike ride and filmed mostly on a helmet-mounted action camera, the movements go from leisurely to chaotic in less than the time it takes to reanimate from a zombie bite, culminating in an undead attack on a child's birthday party.

Contrary to contained horror movies like "REC," having more agency in the great outdoors doesn't matter when the zombies can overwhelm so rapidly. It only takes a split second to get got by one of them. As such, tough dads with melee weapons are overwhelmed after a couple of swings, and a good guy with a gun only dispatches three zombies before yet another comes up from behind. The spread is simply too fast and too overwhelming, making it impossible for the average person to survive and ultimately issuing the same warning that Sánchez and Daniel Myrick put forth in 1999: Don't go into the woods.