What Happened To Buster Keaton? His Hollywood Rise, Fall, And Revival Explained

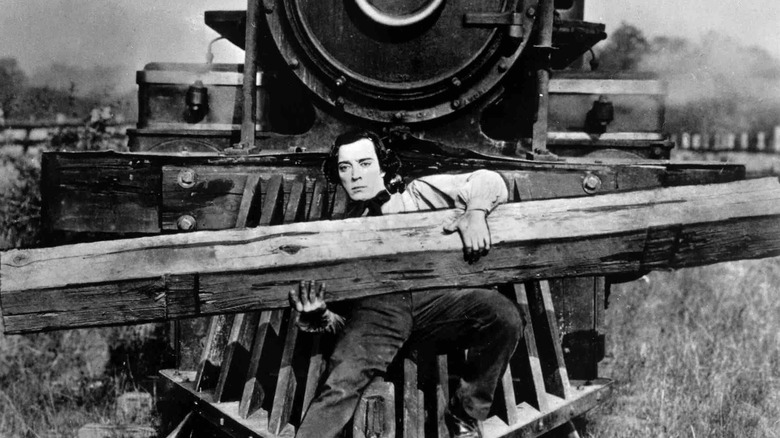

Buster Keaton was one of the biggest silent film stars in Hollywood. Nicknamed "The Great Stone Face," he was known for his trademark stoicism and expressive physical comedy. His fascinating career sadly fizzled out with the invention of talkies. Keaton was so used to telling his stories through action that words escaped his grasp. Still, he remains an undisputed legend of the silver screen.

Keaton first got his nickname, Buster, from none other than Harry Houdini. The silent film star fell down a full flight of stairs at six months old and didn't cry. "Houdini said 'that was sure a buster,' meaning a fall, because that's the only way at the time it was used," he recalled (via A Hard Act to Follow). But his father liked it for a name, and from then on it stuck.

The film star came from a family of vaudeville performers and joined the act at only three years old. This was where he first got his knack for physical comedy. Buster's father made his beatings a regular part of the act, and the audience loved it. Child labor laws prevented him from participating in acrobatics or playing musical instruments like his parents, but "none of [the laws] said you couldn't kick him in the face."

Buster breaks into the movie biz

After years on the stage, a newly adult Keaton decided he wanted to support his family. He went to New York to speak with his family's representative and get himself a job. "While I was leaving that office walking down the street I ran into an old vaudeville performer who was with Fatty Arbuckle," a star from of "[Mack Sennett's] Keystone Cops," Keaton recalled. It was then that Arbuckle asked Keaton the question that would forever change his life: "Have you ever been in a motion picture?" (via BBC).

Arbuckle encouraged Keaton to check out his studio, and he obliged. Old Stone Face found the filmmaking process "fascinating" and was eager to learn how every step of it worked. The first time he appeared onscreen would be in Arbuckle's 1917 comedy "The Butcher Boy." Keaton tries to buy some molasses and, while he has his back turned, Arbuckle pours it into his hat. "He only had to turn me loose in the set and I'd have material in two minutes, because I'd been doing it all my life," Keaton explained, referring to his vaudeville days (via A Hard Act to Follow).

The two comedians worked under producer Joe Skank, who quickly took a shine to Keaton. They made several two-reel comedies in New York before heading out to Hollywood. There, Skank bought Keaton his own studio — Chaplin's old studio, in fact — and they began producing two-reel comedies for MGM. This included the famous short about a newly married couple building a portable home, "One Week."

The golden age of comedy

Keaton made his first full-length feature film, "Our Hospitality," in 1923. He stars as a great fortune's sole heir that falls in love with the daughter of his family's greatest rival, played by his new wife Natalie Talmadge. The picture was a roaring success, but moving into feature-length work was bittersweet for Keaton. The absurd comedy he had explored in his shorter work was diluted when he moved into a longer story format. "We had to stop doing impossible gags and what we called cartoon gags," Keaton told Studs Terkel. "They had to be believable or your story wouldn't hold up."

The comedian then went on to make highly successful films like "The Navigator" and "The General" in the years to follow. He made all of these films without any form of script, which was the norm in the silent days. "We never even thought of writing a script, we didn't need to," he explained. Instead, they approached a film only with a beginning and an ending in mind. "We could always go into any story and pad and fill in the middle, that was the easy part."

The first time Keaton was forced to work with the script was in the 1928 film, "The Cameraman." Keaton plays a photographer who buys a film camera in hopes of impressing one of MGM's newsreel girls. The studio had begun to tighten its grip on all production, even Keaton. This was the last film where he was given any degree of creative authority, and is therefore considered the last true Keaton movie.

Stone Face falls from grace

After "The Cameraman," silent film began to fade into obscurity. Keaton was forced to work more closely to scripts and get into speaking pictures. This wouldn't have bothered him if not for the excessive use of dialogue in early talkies. An influx of New York writers flooded into Hollywood and began "looking for those funny lines, puns, little jokes" in a script, he explained to CBC. Keaton was a physical comic, and it was his view that "when you've got spots in there where you can do things in action without dialogue, you should take advantage of it," he told BBC.

MGM gave Keaton less and less control as the years went on. He was forced to take abnormal roles in weak films, like the 1932 comedy "Speak Easily" with fast-talking comic Jimmy Durante. "They were picking stories and materials without consulting me and I couldn't argue them out of it. I'd only argue about so far and then let it go," he lamented (via A Hard Act to Follow). He turned to drinking and gambling, which led to the end of his marriage and, eventually, his contract with MGM.

From there, Keaton fled to Europe, where he made "Le Roi des Champs-Élysées," a forgotten film with dubbed French dialogue. He then returned to America, signed with Educational Pictures, and returned to making two-reel comedies. From a creative standpoint, this was extremely low-brow stuff— a big fall for Buster. Everyone thought this was the end of Keaton's career.

Keaton's comeback

In the mid-30s Keaton suffered a nervous breakdown and went to rehab. Tail between his legs, he returned to MGM as a gag-writer at 10% of his former salary. There, he worked with the famous comedy troupe, the Marx brothers. "It was an event when you could get all three of them on the set at the same time," he recalled. Keaton admired their comedy, but admitted that their lackadaisical approach "used to really grind my goat."

In the 1950s he forayed into television, which endeared him to the American public again. He enjoyed the live audience, but he found himself up against a major problem. Coming up with enough fresh material to fill a weekly show was "just impossible," he explained to Studs Terkel. "There's only one way you can get material ... youse got to start repeating, stealing," he told BBC. So, he resolved to only make cameos.

On a trip to Paris, a producer noticed the attention that Keaton attracted. It was then that he ordered a theatrical revival of a film of Keaton's choosing. The director chose "The General," cementing the film's reputation as his magnum opus. "I was more proud of that picture than any I ever made," he once said (via Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase).

By the end of his life, Keaton had secured his reputation as a legend of the silver screen. After years of fading into obscurity, he lived to see his genius recognized once again. His revival wasn't too late or too little for him to enjoy, giving his sad story a happy finale.