Akira Toriyama Has A Simple Explanation For All Those Dragon Ball Z Transformations

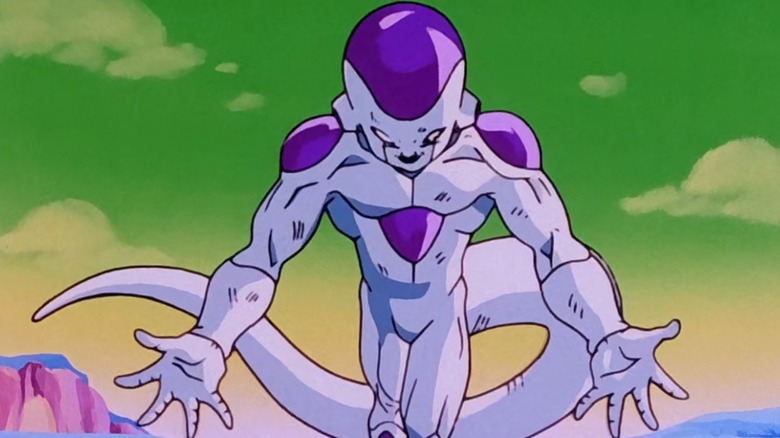

As any fan of the classic shōnen manga and anime "Dragon Ball" ("Dragon Ball Z" for the animated version of the series' back half) can tell you, that series loves its physical transformations. Characters announce their intentions, with a familiar line to the effect of, "this isn't even my final form!" Moments (or episodes) later, they change, sometimes drastically, as with alien tyrant Frieza's move from diminutive prince to massive beast to (pretty much a) Xenomorph. The series' primary alien characters, the Saiyans, would turn Super and find their hair bleached and their eyes turned green after a great deal of screaming.

These transformations served many purposes. Besides amplifying the stakes — would Goku and friends be able to beat an even stronger version of their current enemy? — it brought greater artistic variety to the sometimes punishingly long battles that made up the series' climaxes. The artist behind the manga, Akira Toriyama, a master at creature design, got to flex his creative muscles with the transformations, coming up with villain looks that could be alternately repulsive and hilarious. But his intention with the transformations had nothing to do with making that kind of work happen — in fact, he was hoping that changing the character designs could simplify his process.

Toriyama's original designs

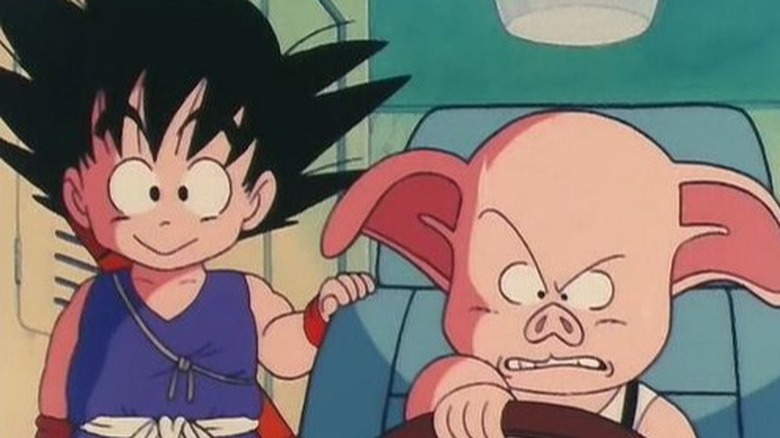

For Akira Toriyama, the creator not just of "Dragon Ball” but of the art design of classic videogames like "Chrono Trigger" and the "Dragon Quest" series, bold, rounded designs took precedent. There's a simplicity to the many of his most iconic characters, whether it's in the young version of Goku or the island-dwelling dirty old man Master Roshi. He had come up in the age of the gag manga, perfectly suited for his talents and sense of humor, and transferred that over to an action manga with the back half of "Dragon Ball," which ballooned far beyond his original intentions.

By the time you get to the more action-packed set of "Dragon Ball" stories, (Frieza, the Androids, Cell, etc.) the character designs evolved somewhat. If anything, there was a shift from rounded cartoonishness to something more realistic (albeit with physiques far beyond what the average human was capable of). It's in that era of "Dragon Ball" that the characters started to become more complex, still just as visually appealing but certainly harder to draw. Toriyama hadn't necessarily planned on that, but he was an artist and a writer for a manga with a deadline. He couldn't always have a plan.

No plans involved

In a 30th anniversary interview for "Dragon Ball," Akira Toriyama clarified his process. "I don't plan things out right from the start; instead, when I think of how to make the story come together, I go, 'Hey, I bet I could use that thing.'" His restless plotting is well-apparent to anybody who reads the manga or watches the anime, and there's often a sense that if he's not feeling a particular story arc, he ends it quickly. When the fans reacted coolly to the villainous Androids 19 and 20, "a fatso and some old guy" as he claims his editor said, they were replaced. This loose planning led to rejected "Dragon Ball" ideas working into the series.

But the most fascinating element to which Toriyama alluded in the interview was his tendency to design himself into a corner, coming up with exhaustively complex villains and then having to recreate them for panel after panel. It was one thing to keep the series brisk with a constant shuffle of antagonists — it was another thing entirely to have to change the characters' appearances. As he said in the interview, "it's awful drawing them once they get all complex."

And so the characters would transform. The Saiyans would turn Super, their dark hair becoming golden (effectively saving Toriyama's assistant from having to ink in the dark hair every panel). The villainous Frieza slowly became more complex until finally he became simple, rounded, and much more threatening.

Great transformations

The mix of a sprawling sci-fi/fantasy narrative with no plan and Akira Toriyama's often-inspired artistry makes up the core appeal of "Dragon Ball" and "Dragon Ball Z." His use of constant character transformations, while sometimes taken to the point of parody, gave him a great chance to bring in new versions of characters with new abilities to discover. That this major aspect of the series, going back to young Goku's tendency to become a giant ape in the moonlight (prior to his controversial aging-up for the series' second half), was built around making things simpler for him is incidental.

As Toriyama himself noted in the series' 30th anniversary interview, he regretted some aspects of the constant transformations. After writing Frieza's claim that he had three transformations altogether, Toriyama had to check himself. "That's kind of a lot... I should've just had him say 'two times' instead." The Frieza he ended up with (the final form) was sleek and simple, immediately identifiable in silhouette and presumably a lot easier to draw. But it was the transformations and their consequent build-up that made him a great villain. The same could be said for Cell (who grew from his bug-like imperfect form to a "Perfect" form by absorbing people) or Majin Buu.