Why The Legendary Katharine Hepburn Was Declared 'Box Office Poison'

Katharine Hepburn reigned over the big screen for six decades. She made a career out of playing fiercely independent women, from the young, outspoken Jo March in 1933's "Little Women" to the obstinate heiress Tracy Lord in George Cukor's "The Philadelphia Story." When paired with her regular costar Spencer Tracy, Hepburn lit up their scenes together with their off-screen chemistry. Yet at one time the whip-smart actress was considered "box office poison" and had to muster all her self-reliance to mount a comeback.

The term "box office poison" had not existed before the late 1930s, according to Catherine Jurca, author of "Hollywood 1938: Motion Pictures' Greatest Year." By 1938, movie attendance was in the pits. It wasn't just because of the recession; industry heads were convinced that regular Americans were avoiding the theaters due to Hollywood's depravity. "Hollywood 1938" describes how Oscar Doob, head of advertising at Loew's, saw the moviegoing milieu at the time:

"The dark, gloomy feeling that movies are on the downgrade; that it is a great risk to buy a movie ticket with all the chances against getting your money's worth; that Hollywood is nuts; that the stars are poison; that show-business is racing to hell!"

A woman rebels

Amid this pessimism in the movie business, the Independent Theater Owners Association took out a full page ad in the May 3, 1938 edition of "The Hollywood Reporter." The ad blasted studios for producing big budget flops with overpaid stars "whose dramatic ability is unquestioned but whose box office draw is nil." The trade group labeled a number of critically acclaimed actors as "box office poison," including Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Joan Crawford, and of course most infamously, Katharine Hepburn.

The theater owners weren't off base in their criticism. By this time, Hepburn had starred in several critically acclaimed flops. Her slump at the box office appears to have started with 1935's "Break of Hearts" and continued the following year with "A Woman Rebels," a feminist melodrama about a woman who defies Victorian social conventions by raising an illegitimate child in Victorian England and becoming a journalist (via The Sunday Post).

The writer Graham Green praised her performance in "Break of Hearts" but also expressed why audiences, particularly men, might fear her, saying:

"Miss Hepburn always makes her young women quite horrifyingly lifelike with their girlish intuitions, their intensity, their ideals which destroy the edge of human pleasure."

As Hepburn continued playing oddball heroines, her popularity may have faltered because she suffered from the same curse that has plagued so many women in the public eye: she was not "likable enough." She defied the politeness that was expected of starlets, refusing to sign fan mail or schmooze reporters (via You Play the Girl).

Baby's not back, yet

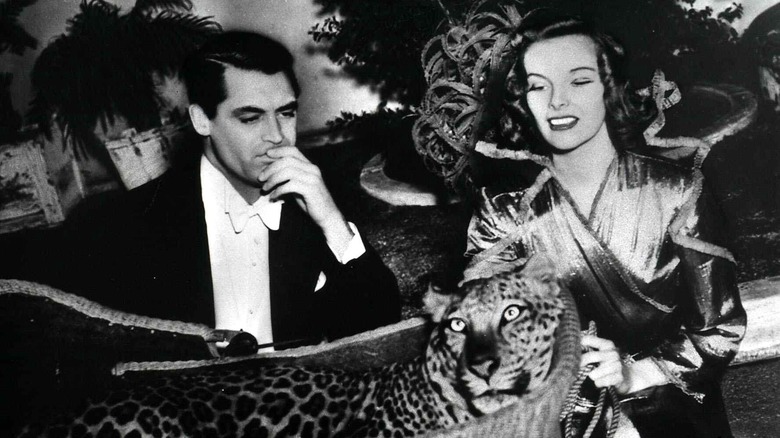

The 1938 screwball comedy "Bringing Up Baby" looked like a departure from her recent roles playing tough women like Mary Queen of Scots. The playful film followed a madcap romance between Hepburn's dizzy heiress and a straight man paleontologist played by a bespectacled Cary Grant, who showed off his acrobatics with hilarious pratfalls.

Hepburn was deemed "box office poison" by the trade group while the movie was still in production, which led RKO to shelve the film before spending more money on advertising (via AFI). It wasn't until Hepburn's then-lover, Howard Hughes, bought RKO and booked "Bringing Up Baby" for the Loew Circuit that the film saw the light of day. As with Hepburn's recent works, the film received good reviews but poor attendance, losing more than $350,000.

The comeback kid

Shortly after the trade group's attack on her and other stars, Hepburn bought out her contract with RKO. After returning to her family home in Connecticut, she began strategizing her comeback. She reunited with playwright Philip Barry, who had written the play "Holiday," the basis for Hepburn's other 1938 film with Grant (via The Frick Pittsburgh). The two collaborated on what would become the Broadway play, "The Philadelphia Story," with Hepburn cast as the lead, Tracy Lord. Following a smash hit run in New York, Hughes purchased the rights to the play for Hepburn, who convinced MGM to cast her in the film version. When the film premiered in 1940, The New York Times eschewed Hepburn's old epithet:

"...The way Miss Hepburn plays her, with the wry things she is given to say, she is an altogether charming character to meet cinematically. Some one was rudely charging a few years ago that Miss Hepburn was 'box-office poison.' If she is, a lot of people don't read labels — including us."

Hepburn never fit the mold of what Hollywood or America wanted her to be. When critics and trade groups called her "box office poison," she countered by creating both a Broadway and film hit.

History has been kinder to Hepburn's flops too; "Bringing Up Baby" is now seen as one of the wittiest screwballs ever produced and the foundation for generations of rom-coms. The film even spawned a quasi-remake, Peter Bogdonavich's "What's Up, Doc?" starring another idiosyncratic actress, Barbra Streisand, as its manic protagonist. In the end, watching Hepburn's decades-long success must have been a bitter pill for Hollywood executives to swallow.