Tom Hanks' Bananas Performance In Elvis Is Good, Actually

"Elvis," the long-awaited biopic of one of music's true icons, premiered last month to strong, if divided, reviews. Baz Luhrmann's take on the life of The King, the man who revolutionized rock and roll in the '50s and became a worldwide phenomenon, was never going to be a subtle affair. His film is long, jam-packed, and has zero interest in mundane matters such as realism. For Luhrmann, Presley's life story was an opportunity for him to further explore his interests in the dazzle of celebrity and the rot under its rhinestoned surface. This means that "Elvis" is loud, bombastic, and full of anachronistic music choices and frenetic editing. Over two hours and forty minutes, everything is thrown at the wall, from groin-thrusting montages to Doja Cat covers of "Hound Dog."

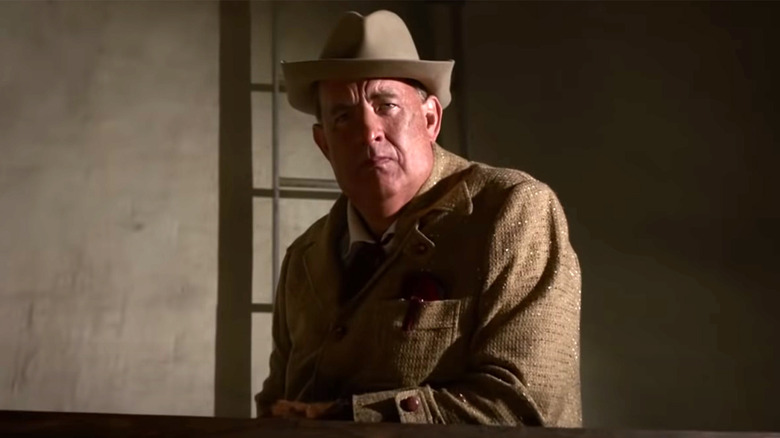

At the heart of this typhoon is Austin Butler, giving a startlingly good performance as Presley. It's through Butler and his charisma that we get to see the oft-parodied Presley as a living, breathing being, the man and not the icon. With Butler, "Elvis" comes close to magnificence, and even the more cynical reviews have agreed that his work is excellent. But there's also one other element that the varied opinions of "Elvis" have united on: Tom Hanks' barmy performance as Colonel Tom Parker. It's bad, so says practically every review.

Critics hate Tom Hanks' performance

IndieWire called Hanks' performance "possibly the most insufferable movie character ever conceived." CNN said that he was "ill-used," using an accent "that can at best be described as punishing." The AV Club declared the performance to be "baffling—even catastrophic." Some have gone so far as to declare it the worst work of Hanks' illustrious and remarkably consistent career.

America's uncle, a man defined by his good guy persona who has widely rejected playing villains over the course of his career, seemed like a curious choice for the role. Parker, the Svengali manager of Presley who coerced him into a decades' long cycle of overwork and financial abuse, was not a nice man. His legacy will always be that of the antagonist to Presley's heroic rise and fall. Knowing this, Luhrmann decided to have the Colonel be the narrator of "Elvis," the unreliable huckster trying to rewrite history in his own favor. He is not merely a villain: he's the ultimate snarling evil. And Hanks plays that with aplomb. All the things he's being dinged for are exactly what the character called for.

There's a moment in the cult British comedy "Garth Marenghi's Darkplace" where the title character, an arrogant hack writer of horror novels, proudly declares, "I know writers who use subtext and they're all cowards." One wonders if Luhrmann and Hanks took this advice to heart for "Elvis." This is a story told, as with all other Luhrmann movies, like a fable, an opera, the kinds of narratives that decry quietness in favor of amplifying excess to expose the machinations of such theatricalities. With "Elvis", we don't merely have a biopic of a famous singer — we have a blindingly vibrant fairy-tale with a handsome prince, the temptations of the dark side, and a big bad wolf. Where Butler is charming and talented, if somewhat naïve to the brutalities of the world, the Colonel is conniving, a salesman who has firmly taken a bite of his own poisoned apple. Such ideas and framing do not call for a delicate performance.

Hanks' performance is pure Baz Luhrmann

Smothered in prosthetics and a fat suit that recalls Dan Aykroyd in "Nothing but Trouble," Hanks utilizes a pseudo-Dutch accent that is about as authentic to the Netherlands as Mike Myers' titular villain is in "Austin Powers: Goldmember." He doesn't so much smile as he slimily grins. While the real Colonel could be charming (even Presley's widow Priscilla admitted that), there's not a speck of that charisma on display here. It seems baffling that anyone would be taken in by this version of Parker, who continues to claim he's an all-American good boy while speaking like a wartime Warner Bros. cartoon caricature. His power over Presley is undeniable, but you wonder if anyone else could ever be under his thrall. Which is, of course, the point. We wonder now, in hindsight, how the likes of Lou Perlman, Phil Spector, and Jamie Spears could wield such damaging control over major music stars, dismissing them as charmless weirdos. One doesn't need to be a megastar to overpower those idolized figures.

In keeping with Luhrmann's grandeur, his anti-reality approach to even the most mundane of narratives, the Colonel's agenda is laid out like that of a Bond villain minutes before he starts firing lasers at 007's nether-regions. He wants to be rich, famous, and written into the history books. He barely even looks at Elvis as a human being. When Parker first hears a record of Presley playing, his eyes practically bulge out of his head with dollar signs in his pupils when he's informed that the kid singing rock and roll isn't Black. Every claim he makes during his narration is almost immediately refuted by what the audience sees, including the Colonel's own schemes. He tries to bleed Presley of every ounce of unique charm he has in the name of profit, only to take credit when Presley does the exact opposite to immense acclaim.

When Presley goes behind his back to organize his now-iconic 1968 comeback special, the Colonel is determined to have him make an anodyne Christmas special devoid of anything remotely challenging or interesting. As he watches new producers create a vibrant, sexy, and thoroughly modern performance, Hanks's panicked expression embodies the fear of an era of old white men in suits losing their meal ticket. A lot of people made a lot of money from Elvis (far more than the man himself ever benefitted from) and their profits depended on him being a pliant puppet who followed the trends they dictated. The Colonel knows this better than anyone, even as he seems pathetically behind with those trends he claims to know so well. Hanks desperately demanding that Elvis sing "Here Comes Santa Claus" (which he pronounces "Santy Claws," repeated so often that it stops sounding like a real phrase) is the echo of "Shut up and sing" that plagued many a musician over the ensuing decades.

Hanks may not be that much like the real Colonel Tom Parker, or any kind of realistic bad guy in an old-school Hollywood biopic, but that was never going to be the performance Luhrmann wanted. His heroes are misty-eyed dreamboats who think of love and art and life. His villains are the antithesis of niceness, often literal mustache-twirlers whom children are encouraged to boo at (see Richard Roxburgh in "Moulin Rouge!" and Bill Hunter in "Strictly Ballroom"). They may not feel like flesh and blood beings but their heightened motivations and cruelty are extremely familiar. It's not as though the music world is devoid of those self-promoting svengalis whose cruel treatment of their workers remain industry-wide open secrets. Amid the glitter and music, Luhrmann's films expose something all too real. A caricature Hanks's performance may be, but what else could it have been?