Jurassic Park Scenes That Aged Terribly

There really should be more dinosaur movies. With the release of "Jurassic Park," the landscape of blockbuster moviemaking was changed forever. As with "Jaws," a movie arguably responsible for blockbuster movies in general, Stephen Speilberg had done it again. Despite its groundbreaking success and state-of-the-art technology, dinosaurs have been all but consigned to the franchise Spielberg started with his adaptation of Michael Crichton's novel of the same name.

Consequently, dino nostalgia is largely limited to the "Jurassic Park" franchise, including the contemporary revival trilogy, "Jurassic World." The last entry, "Jurassic World Dominion," was met with a lukewarm reception. If there are hulking dinosaurs in movies, it's probably a "Jurassic Park" movie. As incredible as the original trilogy is — there's an argument to be made that "Jurassic Park" is one of the best movies of all time — there are still some beats in the original trilogy that haven't aged well. Too much of a good thing can sometimes become rotten, and while none of the subsequent scenes are especially egregious, time hasn't been all that kind to them. Whether it's outdated science or dino beats introduced and quickly discarded, these 10 scenes wouldn't pass Ellie Sattler's smell test.

Hacking in Jurassic Park

It's often omitted from "Jurassic Park" retrospectives, but much like Spielberg's "Jaws," the first entry in the long-running franchise is a de facto horror movie. Spielberg borrows many beats from the horror genre, especially in the film's conclusion. Desperate to escape, the core group of survivors is hunkered down in the control room as a hyper-intelligent Velociraptor tries to open the door.

In a race against time, adolescent Lex (Ariana Richards) is tasked with restoring power to the park, hacking into the system like a "Kim Possible" progenitor. While the scene seems unbelievable today, largely on account of outdated software and an oversimplification of power grids, it's worth noting that the software Lex navigates did and still does exist. According to Wired, the computer is a UNIX system that uses File System Navigator, a 3D organization system, accounting for the park rendition on the screen — with distinct buildings encompassing distinct commands. Real or not, it's nonetheless a bit goofy to see Lex scroll through a computer-generated Jurassic Park while two adults scream bloody murder in the background.

Science in Jurassic Park

This entry comes with a necessary caveat. While a lot of the science in both Michael Crichton's novel and Steven Spielberg's adaptation might retroactively be inaccurate, at the time of release, it was a reasonable evocation of prevailing ideas. Nearly 30 years of progress have rendered some of the movie's key ideas suspect at best.

While the science of the dinosaurs will be saved for later, some thematic touchstones are oversimplified or misinterpreted altogether. Among them is Dr. Ian Malcolm's (Jeff Goldblum) Chaos Theory contention, a theme many contemporary scholars point out wasn't exactly accurate. Most damning is the inciting incident of dino DNA surviving in amber. According to researchers, DNA is too fragile to persist for that long. While amber makes a great preservative, there's no chance it would keep dino DNA in any usable shape for millions of years. Granted, "Jurassic Park" is science fiction, though, in the years since, the "science" has slowly been overtaken by the "fiction."

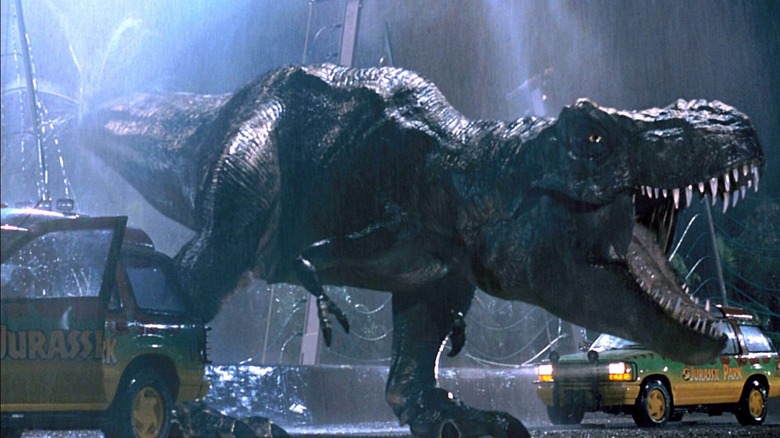

Dinosaurs in Jurassic Park

Of course, the above doesn't account for how inaccurate the appearance and key behaviors of many of the dinosaurs are. The depiction of the Dilophosaurus, which features in a key scene in which Wayne Knight's shady Dennis Nedry is killed, is almost completely incorrect. Rather than human-sized and packed with venom, research shows the Dilophosaurus averaged 20 feet long without any ooey, gooey poison spit.

Additionally, the Tyranosaurus rex, a staple of the franchise, was likely covered in feathers and more colorful and birdlike in real life. While science advisors working on the first movie contend Spielberg was aware of the inaccuracies, the director reportedly made concessions. Most of which were rooted in aesthetics. In other words, were they rendered accurately, the dinosaurs wouldn't have looked nearly as good on screen. One of the most famous instances of dramatic license came with the T-rex's sound design. Most scientists are unclear whether the dino was capable of roaring. As one of the franchise's most iconic elements (that roar is incredible), it's a shame to know that it is a piece of fiction. Although effective, it's not at all grounded in reality.

Udesky's death in Jurassic Park III

"Jurassic Park III" is considerably better than its critical reception might lead audiences to believe. While it's still a far cry from Spielberg's original (though, to be fair, most everything is) it's a fun romp that never takes itself too seriously. As the first entry not directed by Steven Spielberg, expectations were muted. Though in retrospect, it is still more dinosaurs ripping hapless people apart. What more could anyone want?

One of the movie's best moves is repositioning the Velociraptors as the core antagonists. Sure, there's also a Spinosaurus and some terrifying Pteranodons, but they're interludes in a story flanked by some vicious raptors. At one point, mercenary Udesky (Michael Jeter) is separated from the group and captured by raptors. Rather than simply killing him, they bait his tortured cries to draw the rest of the group out. It's terrifying, but it's also a one-off, and in the remainder of the franchise, the raptors never behave quite so tactically again.

San Diego in The Lost World: Jurassic Park

Much like "Jurassic Park III," "The Lost World: Jurassic Park" is better than audiences may remember. As before, it's certainly not "Jurassic Park," but it does have a franchise-best set piece featuring a trailer hanging precariously over a rocky ledge. The late Michael Crichton conceived of a sequel to his original novel after the first film's success. Thus, "The Lost World" was born. It had more dinosaurs, more action, and considerably more Dr. Ian Malcolm.

The centerpiece of "The Lost World" doesn't even take place on Site B, Isla Sorna, but in urban San Diego when a Tyrannosaurus Rex is transported back to the mainland after some greedy investors intend to develop an iteration of Jurassic Park within the continental United States. Of course, the dinosaur is accidentally released and soon rampaging through the streets, flipping cars, eating dogs, and terrifying a group of cinephiles at a local Blockbuster. It's a fantastic sequence that does more to deliver on the promise of "Jurassic World Dominion" than, well, "Jurassic World Dominion." Still, after a terrifying urban rampage, it's unlikely the subsequent "Jurassic World" would ever have been greenlit. While it works on its own, it calls future entries into question, the scene never having been sufficiently reconciled with where the franchise would later go.

Electric fence in Jurassic Park

For first-time viewers, the electric fence sequence in "Jurassic Park" is no doubt effective. As Alan Grant (Sam Neill) tries to lead his two adolescent charges over the fence to safety, Dr. Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern) is simultaneously looking to restore power to the entire park. It's played somewhat for laughs, with Alan even pretending to be shocked by the fence, though he assures the children it's safe to cross.

Unfortunately, Tim (Joseph Mazzello) is slow to cross, and he's zapped by the fence as soon as Ellie restores power (soon encountering a monstrous threat of her own). Ephemerally tense, Tim ends up being fine, and it has little bearing on the remainder of the movie outside some cute character quirks. Further, Alan Grant is introduced as vehemently opposed to the idea of children, and part of "Jurassic Park's" thematic thrust is his slow evolution into protective figure. At this point, however, it's established, so the brief tension with the fence mostly serves to reiterate a characteristic audiences have already picked up on. It's not bad, but after dozens of rewatches, it's unlikely to register as a scene anyone might miss.

Compsognathus attack in The Lost World

Steven Spielberg is renowned for many things, though his penchant for opening movies effectively just might take the cake. "Jurassic Park," "Jaws," and "Raiders of the Lost Ark" (and pretty much his entire filmography) are brimming with sensational, engaging, classic opening sequences. It's a shame, then, that "The Lost World" opens with something of a whimper.

A wealthy family inadvertently docks their yacht along the shoreline of Isla Sorna, unaware it's brimming with dinosaurs. Consequently, young Cathy Bowman (Camilla Belle) is attacked by several little Compsognathus, carnivores close to the size of turkeys. Though likely harmless on their own, they're menacing in numbers, and soon, they're nipping away at poor Cathy. Of course, Cathy ends up being fine, and rather than introducing a second island, the entire opening sequence falls flat. There's little tension or Spielberg charm present. It's a beat that serves a utilitarian, not artistic, purpose.

Parents in Jurassic Park 3

Both William H. Macy and Téa Leoni are formidable performers. Macy's work on "Shameless" is career-best, and Leoni makes "The Family Man" worth watching. For whatever reason, though, their innate talent never made its way to Isla Sorna. While so much of "Jurassic Park III" works better than it should, it's frequently bogged down by some truly bizarre interpersonal drama.

As the divorced parents of the missing Eric (Trevor Morgan), Macy and Leoni's Paul and Amanda Kirby enlist Dr. Alan Grant for an aerial tour of Isla Sorna. With the promise of some fast cash (that he really should have secured before), Grant agrees, unaware that the Kirbys intend to land on the island to search for their son. Their motivations make sense — at least in theory. Despite the danger being made eminently clear, they cannot stop themselves from squabbling. If anything, it serves as a precursor to the blockbuster sensibilities of today in which every movie is contractually obligated to undercut serious moments with a joke. It's hard to find tension in dinosaur jaws when what feels like a rerun of "Everybody Loves Raymond" is chugging along just out of frame.

Gymnastics in The Lost World

Sometimes, a movie doesn't need kids. While it might assist with audience resonance, in a franchise like "Jurassic Park," the dinosaurs are already doing that. Luckily, Vanessa Lee Chester's performance in "The Lost World" is great, and she's never especially grating. As Dr. Ian Malcolm's daughter, Kelly, she is admittedly kind of a throwaway. She's never again mentioned in the franchise, including with Malcolm's return in "Dominion, but she's fun while she's there. Chester does a lot to imbue Kelly with more depth than the script allows for.

That is, of course, until the infamous gymnastics sequence. Some fans love it. Some don't. With a different tone, it would have worked wonderfully, but in the context of "The Lost World," it's an odd and almost cartoonish tonal shift that all but makes "The Lost World" something else entirely. Besieged by raptors at an abandoned InGen base, Kelly makes use of her gymnastics skills to swing, flip, kick, and outwit the pursuing predators. As an isolated moment, it is admittedly very cool, though following the cliffside trailer collapse moments before, it's simply an odd way to conclude the movie's time on Isla Sorna.

Spinosaurus kills the T-Rex in Jurassic Park III

"Jurassic Park III" is a good movie. Some might even say great. But it commits one of cinema's cardinal sins, and for some fans, that act is near unforgivable. The Spinosaurus is a great addition to the "Jurassic Park" canon, accomplishing what legions of "Jurassic World's" Indo-whatevers never could. Ferocious, terrifying, and gorgeously designed, it's the jolt that "Jurassic Park III" really needs. While that's all well and good, what fans likely struggled with was a mid-movie encounter between a T-Rex and the Spinosaurus.

If nothing else, Colin Trevorrow can stage a good dino fight, but there's no fight here. The Spinosaurus makes quick work of its opponent, going so far as to snap its neck. In other words, "Jurassic Park III" killed off the face of its franchise. Sure, this isn't the same Tyrannosaurus from Isla Nublar, but a T-Rex is a T-Rex, and killing one-off so casually in a franchise identified by it is an odd creative choice that dims some of "Jurassic Park III's" luster.