How Drunken Master Completely Changed Jackie Chan's Career

1978 was a great year for kung fu films. First came "The 36th Chamber of Shaolin," featuring the greatest and most detailed martial arts training sequence in cinema to date. Then came "The Seven Deadly Venoms," the beginning of a popular series directed by master of sadomasochistic revenge thrillers Chang Cheh. And then there was "Drunken Master." Released in October of that year, the film was neither an earnest tale of self-improvement like "36th Chamber," nor a rock-beats-scissors festival of violence like "Seven Deadly Venoms." It was a comedy, reinterpreting the Cantonese folk hero Wong Fei-hung as a young lout who learns to harness alcohol as a weapon.

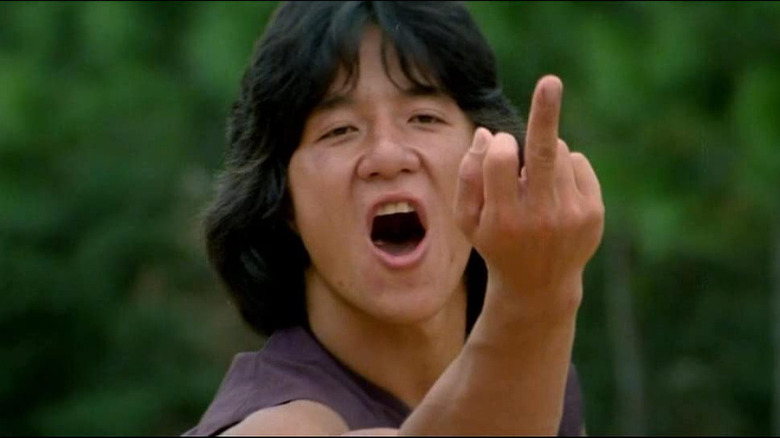

"Drunken Master" was directed by a young Yuen Woo-ping, years before he truly made it as a solo director and action choreographer. But it also marks the breakthrough of Jackie Chan, a former Bruce Lee stunt double who would become an icon in Hong Kong and abroad. "Drunken Master" was not the first collaboration between the two, and it wasn't even the first attempt to reinvent Wong Fei-hung for a new generation. But without "Drunken Master," there would be no "Police Story." While Chan would continue to grow as a performer, he became the star he is today in this film.

A different style to Bruce

When Jackie Chan entered the film industry, Bruce Lee was the biggest star in the game. Chan served as one of Lee's many stunt doubles, but he also fought for his own part, finally scoring a small role in "Enter the Dragon." After Lee's passing, Chan was scouted as a successor by director Lo Wei. Lo is credited for discovering both stars, but his long career only served to calcify his creative instincts. As far as he was concerned, Chan had no right to buck convention. He was just a young actor, and young actors in the industry did as they were told. Chan was frustrated by Lo's conservatism. In an interview with the South China Morning Post, he said:

"I had a different style to Bruce, my own style, so that wasn't working, and I was looking to make a change."

Chan was finally given the chance when Lo Wei loaned him to the production company Seasonal Films. There he had the opportunity to work with an up-and-coming young director, Yuen Woo-ping. Unlike Lo Wei, Yuen had no preconceptions as to what kind of star Chan should be, or even what movie they should make together. When Chan suggested a comedy, Yuen decided to go with it, and he roped in his father, Yuen Siu-tien, to serve as Chan's mentor figure. The final result, Yuen's directorial debut, was "Snake in the Eagle's Shadow." Hong Kong audiences enjoyed the comedy, the martial arts, and Chan's student-teacher relationship with Siu-tien in the film. So for their follow-up, Yuen and Chan decided to give their fans even more of what they wanted.

An unchanging avatar of Confucian virtue

While "Drunken Master" was positioned as a spiritual sequel to "Snake in the Eagle's Shadow," it is in fact a movie about Cantonese folk hero Wong Fei-hung. Wong was born in 1847 and was taught the hung gar martial arts style by his father. His escapades, both real and fictional, are serialized in over a hundred movies since 1949. Kwan Tak-hing played the title character in 81 of the films as an "unchanging avatar of Confucian virtue, a reliable patriarch in a tumultuous world," per Grady Hendrix for Criterion. The films also played a role in the gradual shift from chivalric wuxia films to more grounded kung fu movies, courtesy of director and steward Wu Pang. Over the decades, the character of Wong grew stale. Audiences wanted something more complicated than the old-fashioned hero of earlier films. Seeing an opportunity, the Hong Kong film industry strove to deliver.

A 1976 TV production of "Wong Fei-hung" tackled thornier topics like government corruption and international intrigue, even as it brought back a 70-year-old Kwan to play the lead. Meanwhile, director Lau Kar-leung, who would go on to direct "The 36th Chamber of Shaolin," brought audiences "Challenge of the Masters." "Challenge" presents a young and brash Wong, whose father refuses to teach him martial arts. When he is embarrassed in a match, Wong undergoes grueling training at the hands of a strict master to become worthy of his family's legacy. Two years later, Chan and Yuen would steal this formula for their own purposes. But while "Challenge" would take Wong's crisis of faith seriously, Chan and Yuen would transform his story into a farce.

The eight drunken immortals

"Drunken Master" asks the question, "What if Wong Fei-hung were a dudebro prankster who uses his martial arts skills to avoid responsibility and pick up women?" From the very beginning, Jackie Chan makes choices that reverse Kwan's take on the character. Rather than respect his elders, Chan pokes fun at them. Rather than training hard, he finds new and hilarious ways to escape. It isn't until he is defeated by the ruthless mercenary Thunderleg that he finally starts listening to Beggar So, the film's mentor figure, played by a returning Yuen Siu-tien. Even then, Wong's greatest humiliation comes when Thunderleg makes him walk between his legs and then steals his pants. This is not a movie about Confucian morals; this is a movie about potty humor.

Chan plays Wong as a jerk, but he finds ways to stay on the audience's good side. First, Wong's disgraceful actions are meant to lampoon earlier, strait-laced portrayals of the character. It's not dissimilar to Graham Chapman's portrayal of the legendary King Arthur as a bewildered, exasperated Englishman in "Monty Python and the Holy Grail." Second, Jackie Chan is just as often embarrassed by others throughout the film as he is to embarrass others. When he creeps on a young woman early in the film, the woman's guardian (and his aunt) obliterates him with a flurry of kicks. Later, when he picks a fight in a restaurant out of bravado, he finds himself beaten and outnumbered by the staff. It is only through the help of Beggar So that he escapes. So teaches Wong "drunken martial arts," a purposefully silly style designed so the opponent underestimates the user's power and control.

Jackie Chan always starts beneath his opponents

Over the years, the principles became central to Jackie Chan's modus operandi as a performer. "Every Frame a Painting" defines two such principles in the video "Jackie Chan — How to Do Action Comedy." First, Chan always starts as an underdog to his opponents. Chan's Wong Fei-hung is skilled at the beginning of "Drunken Master," but not yet truly great. It takes until the end of the movie for him to challenge the villain Thunderleg on equal terms, and even then, it is a close fight. Over the course of his career, Chan learned he could never take the audience's trust and sympathy for granted. In "Drunken Master," he works hard to ensure the audience is on his side before he proves himself an action hero in the climax.

Second, Chan is not only unafraid to appear vulnerable, he gets hurt. Wong is beaten over and over again in "Drunken Master." Sometimes this manifests as physical injury: a slapped face, a bitten hand. Just as often, Wong is subjected to fear and embarrassment. When he discovers the female master who beat him up resting at his father's house, he tries to sneak away without acknowledging her. His father calls him over to say hello, and Wong ties himself into pretzels to avoid admitting his guilt. Despite everything, his aunt tells his father what happened, and Wong is disgraced. Not to mention that Wong's "Drunken Master" fighting style requires imbibing concentrated alcohol, putting him into a state where he is even more likely to make stupid decisions and injure himself.

The unbeatable drunken master

For many modern action stars, a willingness to embarrass oneself to entertain the audience as Jackie Chan does is simply not feasible. According to GQ, actors like Dwayne Johnson and Jason Statham have clauses in their contracts for the "Fast & Furious" films stipulating exactly how much abuse their characters were allowed to take in the fiction. Other actors who began as comedy stars, like Chris Pratt of "Parks and Recreation," later abandoned comedy affectations in projects like "The Tomorrow War" and "Jurassic World: Dominion." Tom Cruise is a fascinating case. His early films position him as a superman, but starting with "Edge of Tomorrow," he's made enduring physical punishment a key part of his screen presence. His work in "Mission: Impossible – Fallout" is even better because of how the audience sees him visibly push his limits.

Chan's genius came about by understanding that there need be no separation between modes. He could take punishment and make it funny, then dole it out and make it exciting. Chan and his collaborators were not the first to realize a martial arts film could be hilarious. They were not the first to play with the story of Wong Fei-hung. They simply made "Drunken Master" in the right place, at the right time, to grab an audience who already liked "Snake in Eagle's Shadow" and wanted a bigger and better film. Seen in the light of later Chan masterpieces like "Supercop," "Drunken Master" may seem quaint. Some even argue that its sequel, "Drunken Master II," is superior. But it is clear to anybody watching the opening sequence of this film, as Wong plays keep-away with his teacher's hat, that while we will never have another Bruce Lee, we should forever be grateful for early Jackie Chan.