The 10 Best South Korean Directors Of All Time

The mighty "K-wave" that's been sweeping through the West is extraordinary for a variety of reasons, one of them being that Korea's induction into the world cinema big leagues is a relatively recent occurrence. As two countries with a long track record of hardship, war, repression, and colonialist exploitation, there were few periods in Korean history in which a proper film industry was sustainable. Compiling a list of the greatest Korean directors ever means resisting the temptation to reduce the peninsula's entire history to just the last 25 years, but it also means coming to grips with the fact that, for large stretches of the 20th century, Korea wasn't the best place for great auteurs to flourish.

This list attempts to split the difference, highlighting both the names currently taking the entertainment world by storm as well as their most important forebears. Just keep in mind that, for one pre-secession pioneer, this list will be focused on South Korea. That's not because North Korean cinema is negligible, but rather because historical circumstances have made it difficult for us in the West to study that country's films.

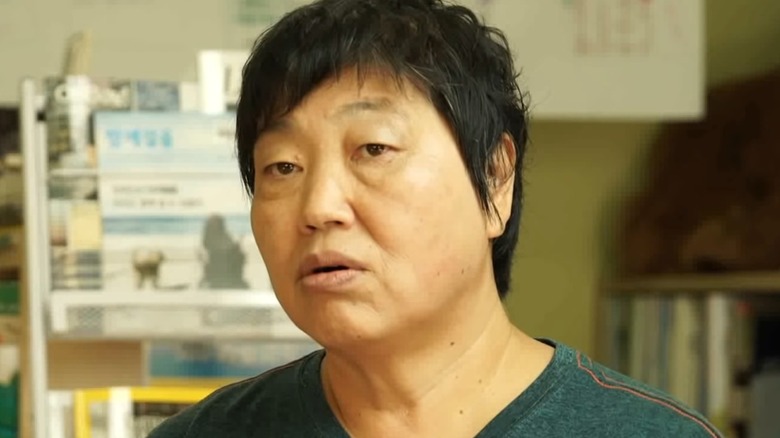

12. Park Cheol-su

One of the qualities that has made South Korean cinema so eagerly discussed around the world, especially in the early-to-mid-2000s, is its willingness to confront hot-button issues, overturn taboos, and explore dark and prickly emotional territory. While obviously a result of new filmmakers' eagerness to make up for time lost to censorship, this challenge-prone disposition was also, to a certain extent, an outgrowth of the country's earlier commercial history. In the slower, more repressive period between the cinematic golden age of the '60s and the ongoing turn-of-the-century renaissance, intense melodramas full of psychosocial contradictions were all the rage in South Korea, obliquely addressing deep-seated audience anxieties born from political structures that couldn't be denounced out loud (via Koreanfilm.org).

Incidentally, one of the most notorious makers of such films also went on to become a standard-bearer for off-the-cuff, confrontational arthouse cinema. A commercially successful director in the '70s and '80s thanks to classic rape-revenge melodramas like "Mother," Park Cheol-su reinvented himself in the '90s as a conscious outsider and erotic experimentalist extraordinaire, making some of the earliest South Korean films to draw international attention (via Film Business Asia), including the 1995 masterpiece "301/302," which became a cult favorite in the West. His films are abrasive, singular, and often uncomfortable — but never anything less than revelatory.

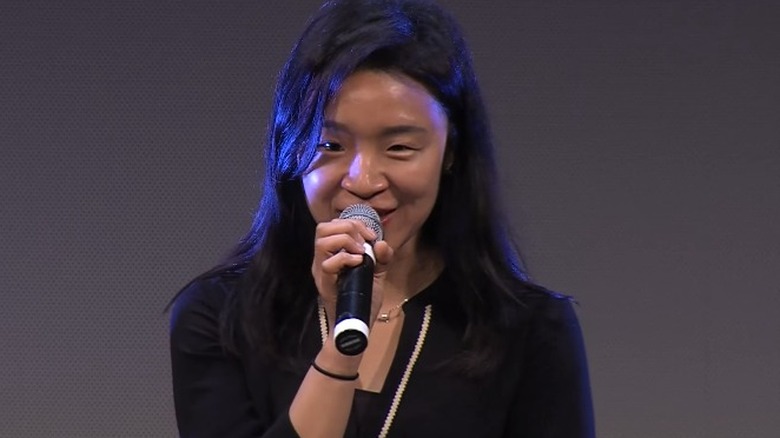

10. Yim Soon-rye

A highly respected veteran with 11 features and one segment in an anthology film under her belt, Yim Soon-rye exemplifies an important aspect of the South Korean cinematic renaissance that is often disregarded by Westerners. The country didn't become a major film hub just because its films grew into international hits; it also developed a strong, healthy domestic market for its productions.

Yim's filmography has cut both ways. With slower, more meditative films like "Three Friends," "Little Forest," and "Waikiki Brothers," she offered up rich portraits of people at the margins of South Korean society, and achieved significant success at overseas festivals. At the same time, her more commercial fare, such as sports drama megahit "Forever the Moment," has been instrumental in helping Korean audiences re-develop a pop lexicon through which they can better understand themselves and each other — something that had been sorely missing in the decades of diminished film production. Yim's savvy movement between both levels of the industry marks her as one of the most important Korean directors of the 21st century.

9. Park Chan-wook

"Park Chan-wook in ninth place?,"the reader inevitably exclaims upon reaching this entry. Let this be a testament to how stacked the field is; anyone from this point on in the ranking could just as well be number one.

There's not much we can say about Park Chan-wook in the span of a single 200-word write-up that the average cinephile doesn't already know by heart. Since the record-shattering box office success of his 2000 action thriller "Joint Security Area," Park has consistently remained not just one of the most popular filmmakers in his home country, but also one of its best-known names abroad, a man who's responsible for many Westerners' first experiences with South Korean entertainment.

From "Oldboy" to "Thirst" to "The Handmaiden," Park is one of those rare artists who's able to capture critical attention and mass audience fascination all at once. With his latest film, "Decision to Leave," drawing rave reviews at Cannes and netting him a long-overdue best director prize, 2022 looks set to once again be his year.

8. Yu Hyun-mok

It is widely agreed upon among film critics and scholars that Yu Hyun-mok is responsible for the greatest South Korean film of all time, the 1961 postwar drama "Aimless Bullet" (pictured above). In fact, it should tell you something about how amazing that film is that it's still held in high esteem around the world today, even though its director's other films haven't traveled quite as much.

While I'm not going to be reductive and try to frame Yu Hyun-mok as some kind of South Korean Orson Welles, it is true that the size of his achievements on "Aimless Bullet" — an enormous, rigorously-composed, dramaturgically robust, politically fearless treatise on the depths of the national trauma that haunted Korea in the mid-20th century — has somewhat eclipsed his later, equally proficient works, which are considered classics in their home country but are still largely waiting to be discovered abroad. In films like "Guests Who Arrived by the Last Train" and "Rainy Days," Yu proved himself as one of the most skillful directors of his time, one who could tackle any kind of story and bring its characters, emotions, and hidden tensions to life with full force.

7. Hong Sang-soo

Few arthouse directors in the 21st century have been able to attract such ardent, fiercely committed followings as Hong Sang-soo. With 27 feature films under his belt in a career that's only lasted for 26 years, this astoundingly productive perennial maverick has managed to become a legend of the worldwide festival circuit by steadfastly refusing to do anything but his own thing.

The go-to buzzword for Hong's filmography tends to be "minimalist"; his films are, after all, almost unbelievably economical in dramaturgy, endlessly taken with the rhythms of people walking, drinking soju, and having casual conversations. But it would be a mistake to think that he ever does just the bare minimum. Each Hong film is the result of a dutiful and attentive method in which he and his actors set out to find the film as they're making it. As The New York Times describes, Hong begins filming with little planning and just a few pre-written lines of dialogue, and is always on the lookout for elusive flashes of grace, beauty, and emotional insight. There's nobody more idiosyncratic or original currently in the game.

6. Kim Ki-young

Although he was part of the generation that spearheaded the Golden Age of South Korean cinema in the '60s, a time when film production was bustling enough to yield hundreds of films a year, the now-revered Kim Ki-young had a markedly different approach to filmmaking than his peers. Rather than subscribe to the national cultural traditions, which relied on subdued emotions and bucolic aesthetics, Kim made movies that were troubling, twisty, feverish, and exacting. You could call him "ahead of his time," if not for the fact that his films were frequent box office successes (via The House of Kim Ki-young).

Kim's masterpiece, the 1961 psychosexual domestic thriller "The Housemaid" (pictured above), took far too long to be rediscovered by both Koreans and Westerners, although the same could be said of the rest of the era's films, which were all but swept under the rug during the years of intensified military repression. However, once it was rediscovered, it went on to influence everything from K-horror to TV dramas to — yes — "Parasite."

5. Yoon Ga-eun

From Yasujirō Ozu to Majid Majidi to Carla Simón, there's a special place in the cinematic Elysian Fields reserved for those filmmakers who are able to capture the singular emotional flurry of childhood. But even with such illustrious company preceding her, there remains something utterly extraordinary about the new paths Yoon Ga-eun is charting into storytelling from a child's point of view.

In the two features, "The World of Us" and "The House of Us," and several shorts that she has written and directed, Yoon has been able to not just do right by her pint-sized protagonists, but to wholly re-envision the world from their perspectives, marshaling all the visual and aural resources at her disposal in service of transporting empathetic experiences. To watch Yoon's movies is to be reminded of all the poignant little trials of growing up that you'd forgotten about, all the momentous shifts, and all the overlooked nuances. Nobody else in the world is making movies like Yoon — and somehow, as mind-boggling as it may be, she's just getting started.

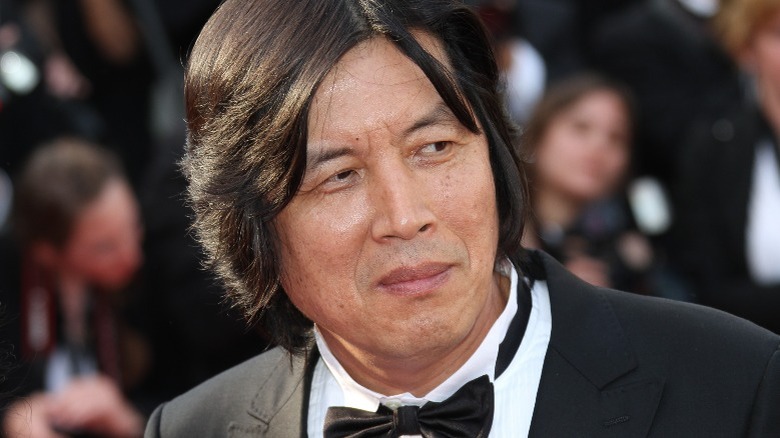

3. Im Kwon-taek

Im Kwon-taek is a living legend. One of the few South Korean filmmakers to have broken through in the 1960s who has remained consistently successful for the following four decades, he's the nation's go-to archetype of the revered, prestigious cineaste, achieving both critical notoriety and something like celebrity status. Not for nothing, he was voted the greatest South Korean filmmaker of all time in a 2019 poll of industry professionals and critics (via Dong-A).

In some ways, Im is the father of them all: Although the Golden Age was already in full swing by the time he got his start as a director, Im was the one responsible for breaking out of national borders and introducing South Korean cinema to the world. With films like "Mandala," "Gilsoddeum" and "The Surrogate Woman," he became the first South Korean festival darling; with his late-period masterwork "Painted Fire," he made history as the first South Korean director to win the best director award at Cannes. And that's not even getting into his 1993 pansori drama "Sopyonje," which was such a blockbuster phenomenon that it single-handedly helped revitalize national audiences' interest in homegrown films. For many people, Im Kwon-taek is Korean cinema.

2. Lee Chang-dong

The vibrancy and variety that defines the 21st-century South Korean film scene has allowed all kinds of great directors to rise to the fore, along with their unique visions and ideas. But even amid that bustle, Lee Chang-dong stands out as one of the most ineffable, unpredictable, mind-bending geniuses working behind a camera in today's world — or, as we might say in internet parlance, he's a galaxy-brain filmmaker.

Arguably the New Korean Cinema director who most deeply and intuitively understands the sheer sense of displacement, despair, and anger bubbling under the country's surface, Lee Chang-dong fashions sweeping tragedies about those living on the margins, presenting his stories with the probing, unflinching eye of a documentarian, only to turn on a dime and reveal himself a poet. His films are some of the hardest and most painful you'll ever watch, but they're even harder to wrap one's head around afterwards, as their scopes expand from acute psychology to clear-eyed politics to a kind of drifter's existentialism, raining down startling insights by the second. A movie like "Burning" or "Secret Sunshine" is the sort of film that leaves you feeling spent and defeated, disbelieving the very existence of what you've just seen. Even after six features, we've only just begun to figure out what Lee is doing to us and to cinema.

1. Bong Joon-ho

Sometimes, it's appropriate to throw caution to the wind. Case in point: 52-year-old Bong Joon-ho is the most important film director in South Korean history.

I'm not just talking about "Parasite," as much as "Parasite" — with its universal acclaim, its box office dominance, its historic awards run, and its lingering cultural impact around the world — is, without exception, a monumental achievement. Hailed even before his 2019 hit as one of modern cinema's most skilled maestros, and with a command of blocking and visual geography that invites the scrutiny of film students everywhere, Bong has combined an almost supernatural level of technical craftsmanship with the principles of an era-defining artist in each and every one of his films.

It's all there in the exuberance and restlessness of his approach to narrative, the boldness with which he speaks truth to power, the finger he has on the pulse of pop culture, the degree to which he understands audiences both local and foreign, and the ease with which he brings together a reverence for his predecessors and dogged forward thought. In every respect, Bong is the epitome of what Korean cinema has accomplished throughout its rocky yet valiant history. More and more, it's clear that there will be a "before Bong Joon-ho" and an "after Bong Joon-ho," not just in South Korea but in film at large.