Elvis Editors Jonathan Redmond And Matt Villa On Crafting Baz Luhrmann's American Epic [Spoiler Interview]

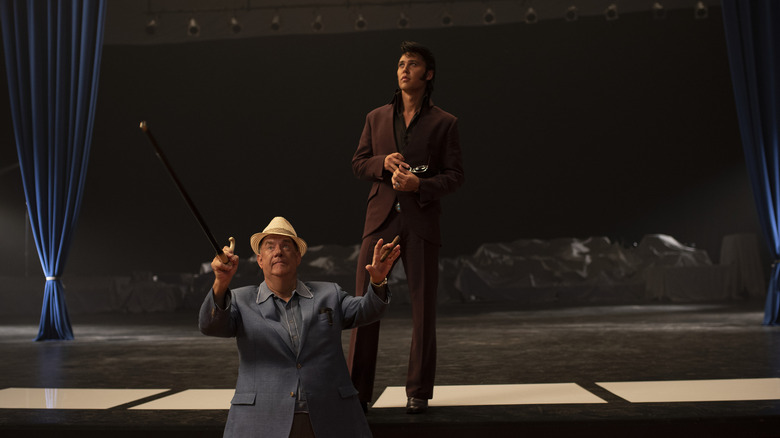

"Elvis" is a mammoth of a film. It's a story that spans decades, covers American and music history, and on top of it all, is told through the eyes of Baz Luhrmann. In the world of film, he is the king when it comes to excess. The "Moulin Rouge!" director is nothing if not a showman, making him a fitting choice to tell the story of Elvis Presley (Austin Butler). However, the biopic is not all about the titular character. It is Colonel Parker (Tom Hanks) telling this story, after all.

It's a sprawling story beyond even Elvis' journey to stardom and descent, which was a fun challenge for editors Jonathan Redmond and Matt Villa. The editing duo had a lot of footage to work with to make "Elvis" a ferociously paced, nearly three-hour drama. Recently, Redmond and Villa told us about how Luhrmann's film reached its final form, the four-and-a-half-hour cut, and what they called "trainspotting" moments.

'The '68 Special was almost like a standalone film'

Baz has said that in post-production he knows where he wants to go, but he doesn't know how he's going to get there. It's a broad question, but how do you both help him get to where he wants to go?

Villa: Well, the beauty of Jonathan and myself, if I can be so bold, is to say that we've both worked with Baz for over 20 years now. We've really developed over those years an understanding of what he wants and the style that he's after. And so, that takes us a long way down the road when he shoots material — and he shoots a lot of material.

We've generally got an idea of what he's going to want. There's a lot of preparation that goes into the shows. Some sequences are quite formed by the time we get there, and they're often shot that way. There's no denying that a lot of it, the majority of it, is sort of created in the cutting room. I think it's just by virtue of the fact that Jonathan and I have this familiarity with what he's after that helps us do that.

Redmond: Lots of time and exploration. Baz, kind of nothing's sacred in terms of what he shot or even the script. We'll throw everything into a blender and see what works. It just takes a lot of time and being open to new ideas. Baz is always open to new ideas.

There is so much visual information in his movies. With "Elvis," his excess is just right for the character, but how do you make sure you don't break the camel's back?

Redmond: There's a line from one of Baz's previous films, "Too much is never enough," from "Moulin Rouge!" Baz certainly lives by that. I think we've got a pretty good sense of when things got too far. I mean, the opening of this movie was a tricky one to put together and it was a bit more frenetic and crazy at one point. Finding the right balance between bombarding the audience with the information, while also entertaining and keeping a clarity of story, a narrative, was a tricky balance. I think we managed to get there in the end, hopefully.

Villa: Along the way, we have lots of internal screenings and we invite fresh eyes in. Jonathan and I obviously see it over and over and over and over again, but we always try to find some other personnel from the film to come in and give us an opinion. People will say if we've gone too far.

How was the original opening of the movie even crazier?

Villa: There was the existence of this device of the Colonel that appears in the film a couple of times where he's in a casino in his hospital gown, reflecting back on the times that he's referring to during the course of the film. It existed a lot more. There was a big opening, almost a big musical number that sets that up. At one point, it wasn't even a casino that he was in at all. He was floating in space at one point and floating in the middle of a Vegas strip at other points.

The opening was about how best to open a film with someone who isn't Elvis, for a start, which we were always aware was going to potentially turn people off, that they were going to want to see Elvis as fast as they could. Also, to establish this device that we were going for, which was to tell the story through the Colonel's eyes. There was the moving back and forth through time. We opened up in 1997, and then we ended up back in 1973. We had to really establish that for the audience. There was a lot to tell the audience without confounding them, which took a lot of exploration to get that balance right.

There is so much story to tell, but you really take your time, in particular, with the comeback special. How did you find the right pace and rhythm for that section of the film?

Redmond: It was quite challenging. At one point, the '68 Special was almost like a standalone film because it was quite lengthy. I think it was such an important part of Elvis' career. He had many, many important parts of his career, but coming out of Act One where we go into the '60s and the movie montage, we fly through that pretty quickly and we learn how Elvis is not doing well in Hollywood anymore, and he wants to sing the music he loves.

The '68 Special, we worked on that quite a lot in pre-production. We had the whole thing storyboarded. Sonically, we had a pretty tight template to shoot to. We had a few challenges with the audio on that track because, basically, the stems [Note: "stems" are isolated audio tracks] that we were using, which is the real Elvis, weren't super high-quality. So it took a lot of work to actually make that sound as exciting as I think it does now.

Villa: We shot a lot more. There was a lot more to it. There was a whole other song that we shot. What do you call it? The sit down performance, where he talked a lot about his involvement in rock and roll and the making of rock and roll. It was a whole other song that was shot for it, which was all great stuff.

Redmond: The original cut of this film is four hours and 20 minutes long, which played. A lot of people saw it and it was an engaging edit of the film with polishing. Obviously, we can't screen that at the theater. You just have to make these choices to bring things down, but the comeback special was definitely one where we knew that it was a big performance for him. There was a lot happening historically around that time, with the assassination of Bobby Kennedy and Elvis coming out of the back of that, sort of realizing that he needed to sing a song of hope. So it was longer at one point, and it was shorter at one point. It's all exploration as to how long these things ultimately play.

'He was a force of nature'

Composer Elliot Wheeler told us that four and a half-hour cut was great.

Villa: Some of the heads of department saw it. We don't normally let many people see, because it's our work at its rawest. We actually call that cut "the kitchen sink" because it's got everything in it, including the kitchen sink. Baz, to his credit, said, "Everyone come in and have a look." And yeah, Elliot's right. With some polishing, obviously, it did play.

I really hope we see it one day.

Redmond: [laughs] It'll be the kitchen sink redux.

Baz can shoot with such a frenetic pace, and yet, he still somehow gives you the time to appreciate a performance. How do you strike that balance, especially with the musical performances?

Villa: A lot of it rested on what performance we were doing at the time. Obviously, his first performance at the hayride, it was our mission to capture the freneticism and the excitement and the energy of that room. You drift towards a faster, more frenetic cut, particularly with screaming fans. It was the first time they were seeing these crazy moves on the stage, so it lent itself to that.

Cut to the comeback special, the challenge there was so much going on stage, but also backstage with the Colonel in the control room, fighting with the executives and then running downstairs and talking to the stage manager. The challenge there was these multiple streams of narrative going at the same time. Oh, the big Russwood Park sequence where the whole purpose, the very purpose of that scene is to have Elvis start slow and lull the Colonel into a false sense of security that things were going to be okay, and then he unleashes himself on stage in complete defiance.

Vegas is Vegas. It was a show and a big concert, so we felt that we were able to slow down the pace a little bit and show more of his performance. There was so much performance to show. The Vegas show was all shot — those three songs that he sang at Vegas were shot in one take over and over again. We had loads and loads of footage to find a good pace for those performances.

For the '68 Special, how closely were you both studying that? Did you make similar cuts to the original special?

Redmond: Pretty closely because as I mentioned earlier on, I think we did kind of do quite a tight template in pre-production. Baz did a number of sequences that he called trainspotting moments where he almost wanted it cut for cut, shot by shot to be exactly the same as the real '68 Special. In the end, we kind of deviated from the trainspotting mode, but we were certainly going there at one point.

In fact, we had cuts basically re-cutting and intercutting the real '68 Special with dramatic voiceovers and storyboards of Colonel running upstairs, downstairs. [Cinematographer] Mandy Walker, for example, her camera team spent a lot of time and effort studying those trainspotting moments. We had a camera angle basically that matched the real show. We could do another cut, which would be exactly the same as basically the recorded television show.

How did that play?

Redmond: Oh, it was good. We had fun. It all boils down to how good Austin is, and he was just phenomenal. We got all trainspotting moments with the camera moves and the camera angles and all the rest, but the ultimate trainspotter was Austin and every twitch and flick of his hair was pitch perfect. He was a force of nature.

Villa: One anecdote, which I'll share just purely as a testament to how extraordinary Austin was, when we first assembled the "If I Can Dream" song when he's in his white suit, everything for Tom Hanks had to be shot before Christmas. We shot all of the control room material first, but we knew that we weren't going to be shooting Austin singing his song until after Christmas. In the meantime, we assembled the control room footage, and we're cutting in footage from Elvis originally singing whenever we wanted to cut down to see what Elvis was singing.

A couple months later when Austin had shot his side of the performance, every time we went to cut Austin in to replace the real Elvis that was in there as a placeholder, it was just frame perfect. His hand was in the exact same spot. His head was in the exact same spot. It was just unbelievable. To the point where we got one of the assistants to do a split screen between real Elvis and Austin playing. It was practically a mirror image of each other. It was extraordinary.

'The beauty of Tom Hanks is Tom Hanks'

Obviously, Baz is known for his spectacle as a director, but he can be just as effective when he has two characters in a car, like when Elvis and Priscilla say goodbye. What's challenging about cutting a sequence as intimate as that one?

Villa: I guess the only challenge is to say how spoiled we are to have such a diverse range of narrative devices to tackle. The tarmac scene is definitely one of my favorite scenes. Another one is the scene in the dressing room when the Colonel says to Elvis, "The audience is just a plant and they were being told when to applaud for you." Some of those two-handers in the film are a real joy to cut because you've got two amazing actors in Tom and Austin, and in the tarmac scene, Austin and Olivia.

They're just a joy to cut for a whole different reason, but just [it's just as joyful to edit] their performances. Baz's films are such an emotional rollercoaster that goes from this fun freneticism to these dramatic two-handers that are equally as fun to cut and put together because the talent on screen is so amazing.

Baz sometimes has alternate endings. Did "Elvis" always end with "Unchained Melody?"

Redmond: We always planned to end with "Unchained Melody." At one point, we actually did a cut of "Unchained Melody," which is quite similar to the final version in pre-production. In fact, we actually used it as part of the pitch to the studio using the original concert footage of Elvis intercut with stock footage and shots of him when he was younger and more beautiful.

We did shoot Austin performing "Unchained Melody" in its entirety. We'd planned and scripted to cut to the real Elvis, but at one point we were finding it very hard to get permission to use that footage. It was only actually in the final weeks that material came in for real. We were very thankful.

I personally love that sequence. I love the cut to the real Elvis, and I've seen it hundreds of times and never failed to cry at that moment. I find it so powerful, so emotional, especially having learned so much about the man, to actually see him singing his heart out shortly before he died.

That was planned. It was scripted. We didn't really have any alternative endings. There was a little bit of back and forth on informational cards at the end. At one of our preview screenings, the audience felt a little cheated about what happened to Colonel Parker. Did he get his comeuppance and all the rest? We tweaked those cards at the end to try to help.

It's a real joy to watch Tom Hanks play a villain, but Baz has said he didn't want the Colonel portrayed as just a villain. Since you're shaping that performance and character, how'd you try to make sure he was more than just the villain?

Villa: It was the subject of some exploration. How much do we have him as more of just a mischievous character versus an actual villain? Yeah, it took some exploration to walk the line. The beauty of Tom Hanks is Tom Hanks — he gave all manner of versions of the performance. We had the luxury of being able to skew that line at will because he's just so amazing. Just with the flick of an eye, he can give over what his internal intentions are.

But you're right, Jack. We were cognizant of it, just sort of making sure he wasn't an absolute complete villain, but at the same time, the story we were telling is that he had Elvis trapped and he had this mysterious background. At one point, there was more about what that background was, which sort of got left behind in various cuts. But yeah, it was an interesting character to put on screen.

You have the Colonel's and Elvis' story to tell, but also, American history. Again, how did you find the right balance between both character and the story Baz wanted to tell about America?

Redmond: One interesting thing I think we found while kind of researching Elvis was all those cultural milestones in some of the early reels. We almost had Walter Cronkite kind of narrating what's going on in America. In the '60s, JFK died, Bobby Kennedy, MLK died, the Vietnam War, Elvis descending into irrelevance before he comes back and becomes the king of Vegas.

The race story was a very important part of the film from day one. Baz thought you can't tell the story of Elvis without telling the story of race during his time. From day one, that was a very important topic. I thought it brought an amazing richness to the movie. B.B. King, Little Richard, Big Mama Thornton, it really showed where Elvis's roots came from. Hopefully, it'll be informative to audiences as well.

Are there any moments in particular you miss that got cut?

Redmond: Oh yeah.

Villa: Yeah, there's lots of great stuff in there, a lot of wonderful dramatic moments. There's a longer version of all the performances, which are all fun. I think some of the stuff that we let go kicking and screaming were some more character building moments in the early years between his band, and in the later years, in the decline of Elvis. That was much more dramatized, his decline after the excitement of the Vegas years into his more adult state.

It's a part of the game that we had to go through and choose what kept the story on point. For example, there's a whole big scene that isn't seen between Elvis and his first girlfriend, Dixie Locke, which is a beautiful scene. It was on a beautiful set and it was well-shot and well-acted. In the broad scheme of the whole film, it wasn't keeping the story on point, particularly in those early years. So yeah, lots of wonderful stuff that may or may not one day be seen. Here's hoping.

It makes sense, though. Even at two hours and 40 minutes, it feels propulsive.

Villa: Oh, great. Yeah, that was the idea. It was always about the Colonel and Elvis's relationship, so a lot of these other relationships, while beautiful to see on screen, just weren't really that necessary in the broad scheme of things.

"Elvis" is now playing in theaters.