How To Write A Scary Movie Scene, According To Sinister And Black Phone Writer C. Robert Cargill

Screenwriter C. Robert Cargill, co-writer of "The Black Phone" as well as "Sinister" and "Doctor Strange," runs one of the most encouraging Twitter accounts that an aspiring author can read. Cargill points out that perfecting one's craft will not happen if one never finishes a project. As he frequently likes to say: Just. Keep. Writing. A completed project can be adjusted. A project stymied by concerns over its structure and perfection will never see the light of day.

Cargill's "Sinister" was not only a massive success (it has made $82 million worldwide on a budget of $3 million) but, according to a 2020 study in Forbes, it was scientifically revealed to be the scariest film of all time (measured by a test audience's heartrate). So one might safely extrapolate that Cargill knows what he's talking about, at least when it comes to horror. Early reviews of "The Black Phone" are already bearing this out.

Naturally, curious journalists and aspiring authors would like to ask Cargill about his secrets to writing great horror stories. When /Film's own Jacob Hall recently sat down with Cargill, he did just that. Cargill was open enough to share a very practical piece of advice that can be emulated and can make your own horror story that much more gripping. Ever helpful, Cargill aims to aid.

Short sentences

There is a widely assumed rule about screenwriting that every page of a script equals roughly one minute of screen time. A 90-minute movie has a 90-page script. This, of course, has as many exceptions as examples, but it's still generally considered Hollywood fact. The more notable exceptions come from horror, as a scene of slow, creeping dread can be condensed to a single sentence in a screenplay. Cargill knows this well, and spoke eloquently about the effects a short script can have on a reader, and how brief statements can expand an audience's mind into more horrific spaces.

"Short, tight sentences. There's a weird psychological effect. Long sentences make people comfortable, short sentences, make people tense. And what you do is as you get into the scene, you start shortening up your sentences and then you start using paragraphs and you start using just straight up single lines of what's happening. Because in horror, horror has a weird thing to it that it is longer on the screen than it is on the page. Because a single sentence of, 'Ellison walks down the hallway very slowly carrying a bat.' It takes you three seconds to read that sentence, but that's 30 seconds on the screen."

An interesting piece of trivia relevant to this statement. David Lynch's original script for "Eraserhead" was a mere 22 pages long, while the finished film ran 89 minutes. One cannot argue that "Eraserhead" is not one of the most terrifying films ever made.

Purple prose

Pacing seems to be a concern of Cargill's as a script has to read on the page the way it's meant to feel on the screen. As such, a sense of creeping dread might be filled in with a lot of extended descriptions, a layout of the mood, and an explicit portrait of the exact tone the screenwriter wants. Cargill seems to feel that recent screenwriting trends have been steering many authors away from the sort of curt, direct writing he practices. He notes that a lot of character descriptions in particular are less about vital statistics and more about the nature of the character themselves.

"[Y]ou want to give people that slow paced tense feeling while they're reading that scene. I mean, there's advice about you shouldn't put purple prose into scripts and that's been changing a lot in recent years ... You don't want to do it too much, because you often have people spending half a paragraph giving us poetry that's never going to read. But there's a big change in how screenwriters are writing character descriptions, because we're moving away from 'Maddie, nine, white. Young girl dressed like this.' Like we're moving away from that and more towards the impressions of the characters, as to give more options for casting."

Cargill argues that those impressions serve actors better than they do readers. An actor given a basic physical description is given no footnotes to the character. A director and an actor can work together to create a character from a vague script, of course, but an explicit script will give both actor and director a more solid place to start from.

Can I play sunshine in the apocalypse?

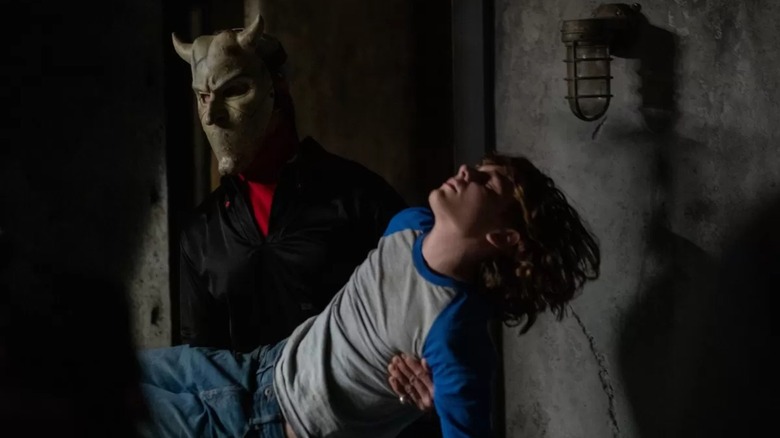

Cargill may be referring specifically to the character of Gwen (Madeleine McGraw), the young sister of Finney (Mason Thames) "The Black Phone's" protagonist. Gwen and Finney live with an abusive widower, are picked on at school, and seem to have very little positive happening to them when Finney is kidnapped by a brutal serial killer. Small moments of solidarity and warmth become everything to Gwen and Finney, and their mutual care buoys them both.

"[Give] tools to the actors and actresses where it's like, 'Oh yeah, I can play a nine year old white girl to, can I play sunshine in the apocalypse? Can I be that sunlight in someone's dark life?' And that gives, that one line gives an actress a lot to play around with and a lot to build on, especially when they're coming into audition. As opposed to, "Well, now I've got to try to read into the nuance of all this stuff."

As noted above, these types of explicit descriptors denote a rising trend. It may have certainly helped with McGraw, whose alternately wounded and wrathful performance is pretty amazing in "The Black Phone."

"And you're seeing more and more screenwriters writing single sentence descriptors of characters that just give us who their character is in a nutshell. So that we then get it while we're reading it. Because there's a lot of stuff that comes from performance that you never can experience on the page. And so giving a little bit of that flavor in the... A little bit of poetry in your description can go a long way for an audience to really get what this character is. And so that's pretty much that."

"The Black Phone" opens in theaters on June 24.