Terry Gilliam's Monty Python Frustrations Found An Outlet In Holy Grail

Prior to "Monty Python's Flying Circus," its individual members were scattered across multiple developing satire TV shows, all notable in their own rights. John Cleese and Graham Chapman were two of the many writers on 1962's "That Was the Week that Was," and appeared on screen together on "At Last, the 1948 Show" in 1967. Michael Palin, Terry Jones, and Eric Idle, meanwhile, had appeared on the very silly program "Do Not Adjust Your Set," also in 1967. The American cartoonist Terry Gilliam, meanwhile, moved from drawing comics for the magazine "Help!" (founded by MAD Magazine luminary Harvey Kurtzman), to doing animations for "Do Not Adjust Your Set." A new sketch comedy show was eventually conceived with all six men, and in 1969 "Monty Python's Flying Circus" debuted, quickly establishing itself as one of the most significant and oddest TV shows in comedy history.

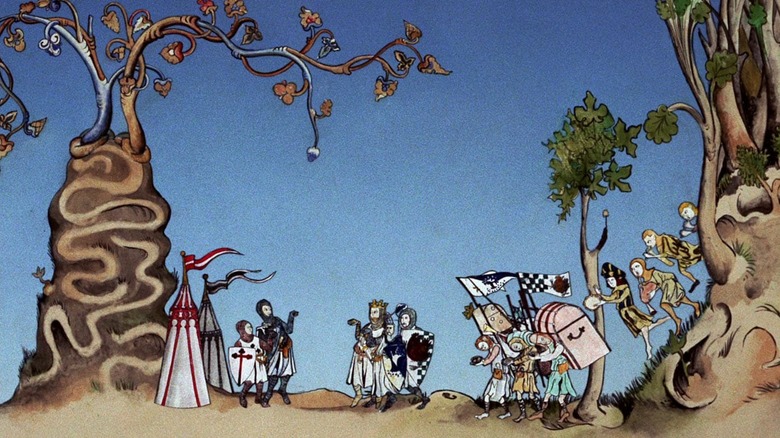

The approach to "Flying Circus" was simple: No punchlines. A sketch didn't have to end with a conclusion, and the troupe would be encouraged to link one sketch to the next, sans ending, by whatever means necessary. Often the links would be surreal paper cutout animations by Gilliam.

"Flying Circus" was also a fast-and-loose affair, beholden to the usual breakneck schedules often applied to BBC television back in the day. In a 1996 interview with the online magazine Wide Angle/Closeup, Gilliam was asked about his days working on the show, and he revealed the fast filming schedule left the show lacking in a certain visual dynamism that he wouldn't be able to explore in his own idiom until he became a notable film director years later.

Light Entertainment

Every episode of "Flying Circus," it should be noted, was directed either by Ian McNaughton or John Howard Davies, two longtime TV veterans who somehow understood what the Pythons were getting at, but who also had an eye on how to make a show under budget and on time. Gilliam felt that their fast-and-loose shooting schedule led to predictable looks and lighting setups that were hardly the most visually intriguing thing in the world.

"It was just annoying because everything was done so fast and shoddily, I thought. Everything was, there was very little time to get real atmosphere on the screen, or to shoot it dramatically enough or exciting enough. It's the nature of television: you don't have time to work."

Parts of "Flying Circus" were shot on video in a studio while location shoots were captured on film (the differing visual qualities were often played with). Gilliam, aching for something that at least looked different, expressed his frustration at the notion of "comedy lighting." Sitcom lighting had been a common staple since the days of "I Love Lucy" (with lighting invented by the legendary director Karl Freund) and sketch comedy programs in England in the 1960s hadn't evolved too much past that. Says Gilliam:

"We weren't doing drama, we were doing comedy, which fell under 'Light Entertainment,' and light seemed to be required constantly so that you could see the joke! Feel the joke! And I just always had stronger visual sense than we were able to get on in those filmings."

Pasolini and the Holy Grail

Concurrently with the show, in 1971, a collection of "Flying Circus" skits were collected into an anthology film called "And Now For Something Completely Different," so the troupe was no stranger to cinemas. Following the conclusion of "Flying Circus" in 1974, the troupe elected to make "Monty Python and the Holy Grail," a more focused — but equally punchline-free — riff on Arthurian legends. Jones and Gilliam are the credited directors on "Holy Grail," although according to the commentary track on the film's home video releases, Jones served as "primary" director, whereas Gilliam's job was more akin to that of an elaborate production designer ("Holy Grail" was shot by cinematographer Terry Bedford). Gilliam was happier with the muddier, more cinematic look of the film:

"[W]hen we were able to do 'Holy Grail,' and direct it ourselves, it looked a lot better. I think the jokes were funnier because the world was believable, as opposed to some cheap LE lightweight ... [W]e approached 'Grail' as seriously as Pasolini did. We were watching Pasolini films a lot at that time because he, more than anybody, seemed to be able to capture a place and period in a very simple but really effective way. It wasn't "El Cid" and the big epics, it was much smaller. But really, you could feel it, you could smell it, you could hear it. That I thought was excellent. What was interesting about the Pasolini films is that a lot of them were designed by Dante Ferretti. But we always felt, Terry and I always used to feel that if the comedy could come out of the sense of a real place, a real world, it was always going to be stronger.

Strong it was. "Holy Grail" is hysterical.

Gilliam's disagreements

Gilliam admits, however, to bickering with Jones from time to time, finding his co-director to be sentimental about shooting conditions and beholden to his own good or bad moods. This became irksome during the editing process, because Jones wanted to keep the takes that gave him nostalgia, and for Gilliam the film came first:

"We used to have disagreements because I felt Terry wasn't looking at the film as a piece of film, he was looking at it with the memory of what happened on the day it was being shot. So if it was a good day, we had a good time, the sun was shining, the food wonderful, he seemed to remember that when he looked at these images. But they're not there for anybody else. This was a battle we had on several scenes where he was seeing stuff that wasn't on the film. And I said they're nothing more than what you see right here."

The smoky, muddy "Holy Grail" is, to this day, often included on lists of the Funniest Films of All Time, so whatever the arguments were, the troupe came out on the other side with a success. Gilliam went on to direct cult hits like "Brazil," "12 Monkeys," and "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas." His films are mostly, infamously met with production problems.

Gilliam has, in recent years, become a controversial figure, speaking out against the #MeToo movement, petitioning for the exoneration of Roman Polanski, defending Harvey Weinstein, and whining about prejudice against white males. The director, now 81, went so far as to renounce his U.S. citizenship. His latest film was the 2018 outing "The Man Who Killed Don Quixote" with Jonathan Pryce and Adam Driver. It's available on Fubo, Hulu, Tubi, and Crackle.

"Holy Grail" is on Netflix.