The Daily Stream: Kwaidan Offers Four Japanese Ghost Stories With Universal Themes

(Welcome to The Daily Stream, an ongoing series in which the /Film team shares what they've been watching, why it's worth checking out, and where you can stream it.)

The Movie: "Kwaidan"

Where You Can Stream It: HBO Max, The Criterion Channel, DirecTV

The Pitch: Four Japanese folk tales come to life in Masaki Kobayashi's visually inventive '60s horror anthology, which remains spooky and timeless in its evocation of people haunted by secrets and regret.

I used to work at an English conversation school in Tokyo, and group discussions on Halloween often fell into a recounting of campfire tales and urban legends like that of Kuchisake-onna ("The Slit-Mouthed Woman") and Toire no Hanako-san ("Hanako of the Toilet"). We stopped short of a field trip to the restroom to check the stalls for Hanako and/or turn off the lights and summon Candyman or Bloody Mary as a frightful form of cross-cultural exchange. But "Kwaidan" offers something like one of those annual spook fests. At least two of these tales of humans interacting with the spirit world are ones I had heard students retell — true to their longevity in the oral tradition — before I ever saw the movie.

Horror anthologies can be a mixed bag if for no other reason than because many of them see filmmakers with different sensibilities and skillsets (or talent levels) plying their trade in the same entertainment package in a way that invites immediate comparison. "Kwaidan" bucks the trend of uneven anthology offerings with a steady collection of ghost stories, told under pink and yellow skies with giant eyes in them, by one writer and one director. There are no weak entries in this collection, adapted from the writings of Lafcadio Hearn, who himself was drawing from Japanese folklore in his "Stories and Studies of Strange Things."

Why it's essential viewing

Guillermo del Toro called "Kwaidan" "one of the most perfect films artistically" he's ever seen. The movie received a Jury Prize at Cannes and an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film, and beyond the sheer technical prowess of its filmmaking, it endures on the simple strength of its storytelling. Kobayashi brings his mythic vision to Yoko Mizuki's screenplay, drawing the viewer in and keeping their senses engaged for three hours.

There's an intermission, so if you need a bathroom break, that's doable, but beware of Hanako of the Toilet. She's not in this anthology, but the Woman of the Snow and Hoichi the Earless are.

J-horror movies have a thing about hair, and when you see "Kwaidan," you'll soon realize that fixation predates "The Ring" or "Dark Water" or any of the other films in the turn-of-the-millennium genre boom. The first 40-minute segment in "Kwaidan" — about the length of a standard TV drama sans commercials — is Kurokami, which translates as, "The Black Hair." It's about a restless samurai (Rentarō Mikuni) who wants a better life for himself. He walks out on his first wife (Michiyo Aratama) and marries into a rich family with the kind of aristocratic daughter who boasts black teeth and shaved eyebrows (ohaguro and hikimayu being a thing once, too, along with the ever-flowing black hair).

The samurai misses his old life with his first wife in Kyoto, and Kobayashi is artful about showcasing his inner life through flashes of imagery, which come to him even as he draws back his bow and arrow on horseback. (Sidebar: eating basashi, or raw horse meat, and then watching mounted yabusame archers like him compete, as I've done in my wife's hometown of Fujinomiya near Mount Fuji, is its own "study of strange things.")

Black hair and white snow

"The Black Hair" taps into basic human feelings of regret and nostalgia, the realization that, no, the grass is not always greener on the other side, and yes, you don't know what you've got till it's gone sometimes. Observe how the camera tilts and takes on Dutch angles, reflecting the samurai's psychological state, as he returns to Kyoto to find his former house overgrown with weeds, the cobwebs of old memories, and other surprises. His first wife, a weaver, is still there spinning her loom, and she hasn't aged a day...

Tatsuya Nakadai, who played the gun-toting antagonist in "Yojimbo," stars in the second chapter of "Kwaidan," which is based on legends of Yuki-onna, "The Woman of the Snow." (Another Akira Kurosawa regular, Takashi Shimura, shows up later.) Thematically, this chapter hinges on the question: could you keep a secret to save your life? Nakadai plays Minokichi, a woodcutter who gets caught in a snowstorm, only to come face-to-face with a woman in white who can freeze men to death by blowing on them.

She takes pity on Minokichi because he's a bishōnen, not in the modern androgynous sense, just in the handsome sense. Sparing his life, she swears him to secrecy on pain of death. Sometime later, Minokichi meets a woman headed for Edo (the old name for Tokyo) "with no definite plans." Her name happens to be Yuki, and to remove any trace of doubt about its meaning, we soon hear children singing a folk song, beginning with the words Yuki konkon ("Heavy snow.")

Yuki (Keiko Kishi) bears Minokichi three children, and the villagers think her a good wife. But like the one in "The Black Hair," she's also something of a mystery woman who never seems to get any older.

Drink it or deny it

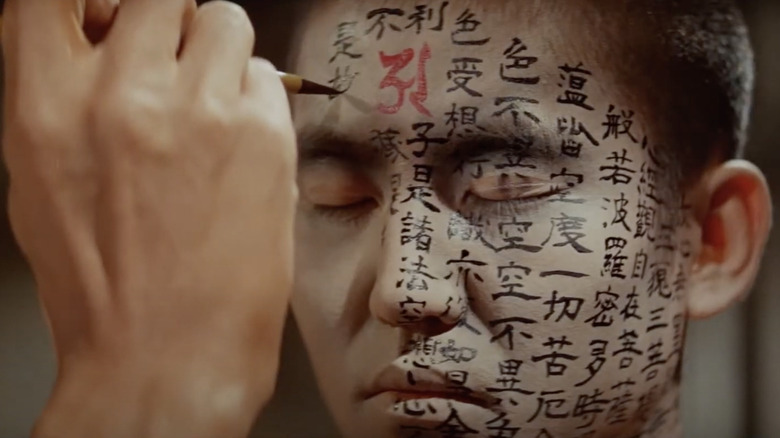

The longest of the four chapters in "Kwaidan" is the one that features the indelible image of Hoichi (Katsuo Nakamura) having the Heart Sūtra drawn all over his face. "Kwaidan" doubles as folk horror, and like "The Woman of the Snow," this chapter opens with a shot establishing the topography (in this case, waves crashing against rocks, instead of snow falling among trees). "Hoichi the Earless" has an oblique beginning that puts us down in the middle of a sea battle as a voice chants out a recitation of it over a stringed instrument. Skies of fire and seas of blood are juxtaposed with murals or scroll paintings and the sense that history is coming to life before our eyes.

Hoichi is a blind biwa player who is summoned to perform for a court of imperial ghosts. As one leads him there by the hand, Hoichi says, "I don't deserve such good fortune," not really understanding the nature of his situation—that these are dead people. The ghosts want to hear the tale of their final battle, which we've just seen, recited the way only Hoichi can.

It's "A Portrait of the Artist as a Ghost Whisperer." Hoichi communes with the dead more than the living, and there's a danger in that for any of us, whether it be sifting through dead letters or the detritus of pop culture.

The final, abbreviated segment of "Kwaidan," Chawan no Naka ("In a Cup of Tea"), describes itself as an unfinished "story about a man who swallows down another's soul." Kannai (Kan'emon Nakamura) beholds a face that is not his own reflected in his tea.

When you see a ghost, you can either drink it down or deny it. My advice would be not to deny "Kwaidan."