Why Universal's Frankenstein Was Censored Years After Release

Boris Karloff made a career-defining choice when he agreed to play the Creature in Universal's "Frankenstein" (1931). Directed by James Whale, the classic horror movie was a massive hit. Karloff, playing an unspeaking, almost child-like version of Frankenstein's monster, terrified audiences, and he went on to become one of the most beloved actors from the classic horror era.

"Frankenstein" wasn't the first movie adaptation of Shelley's novel — there are two lost "Frankenstein" silent movies — and it certainly wasn't the last. It was, however, arguably the most influential — with the Creature's design, the laboratory effects, and Colin Clive's mad scientist look still being icons in popular culture today. The movie is striking; the tall vertical sets, the dramatic shadows, and the claustrophobic, close-up framing shots help develop the movie's spooky and unsettling feel. Although tame by today's standards, in the '30s the movie was downright terrifying — so much so that it had to be censored in certain regions upon release.

And for much of the movie's 90-year history, audiences only saw the censored version.

Frankenstein was censored

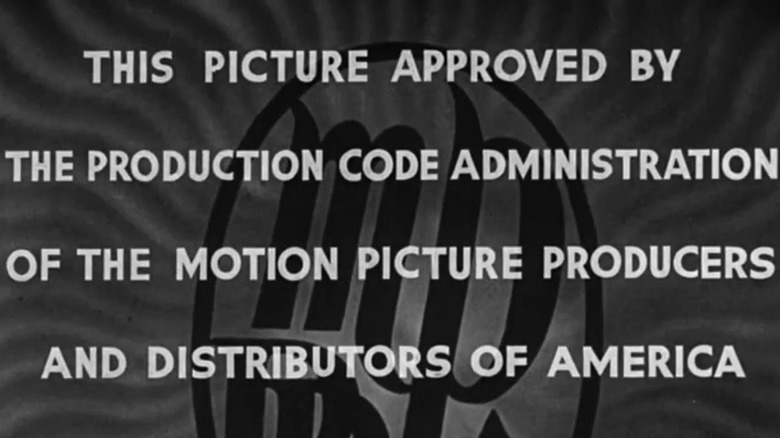

"Frankenstein" was created during an awkward point in Hollywood history; deemed the "pre-code" period, the gap between when sound movies became the norm in 1929 until the Production Code Administration (PCA) was formed in 1934 saw a creative surge of movies that dared to offend. As Thomas Doherty notes in his book "Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema 1930–1934," even though the Motion Picture Production Code (aka Hays Code) was created in 1930, there was no official body to enforce it, allowing filmmakers to stretch the rules.

There is a major caveat to the "Pre-Code" label: regional censorship boards did exist and were active during this time. "Frankenstein" may have been able to push the boundaries of what could be shown onscreen, but it was subject to cuts and restrictions in certain areas. As James Curtis writes in his biography "James Whale: A New World of Gods and Monsters":

"Frankenstein" was cut by censor boards in at least half a dozen states. Small towns in Massachusetts actually banned the film outright, and theaters in Virgina, after complaints from parents, stopped admitting kids under 14 unless accompanied by an adult.

The Kansas State Board of Censors made 31 separate deletions for the reasons of cruelty, adding that "Frankenstein," in the opinion of the Board, "tended to debase morals." ... the board reduced their deletions to just ten, but not before reports of the original 31 had been created.

Such cuts were made to the prints of the film that were sent out to those areas; however, when the movie was re-released to theaters in 1938 — following the success of "Bride of Frankenstein" — cuts to the objectionable content were made to the master copy itself.

The infamous drowning scene

As Curtis notes in "James Whale: A New World of Gods and Monsters," the "infamous drowning scene" was the main source of concern in "Frankenstein," although there were other moments too that would be cut from the original film:

When the film was reissued in 1938, the scene was removed from the negative under the stricter dictates of the Production Code Administration and remained lost until 1985, when its partial restoration was made possible by the discovery of a trim from the original release.

The Maria scene is an interesting one: as Robert Horton notes in his Cultographies book "Frankenstein," by cutting that tragic scene short — and not showing the Creature's motivation and reaction to the child's death — "it actually made the implications of Maria's lifeless body in a subsequent scene more disturbing."

Horton goes on to describe other "Frankenstein" scenes that were censored: the scene with the Creature stalking Elizabeth in her bedroom was shortened, lines of dialogue were removed or altered, and the discovery of Fritz's corpse was removed. Colin Clive's Henry Frankenstein saying "I know what it feels like to be God" was cut and covered with a thunder crack, effectively creating the "it's alive!" lightning strike trope. The documentary "The Frankenstein Files: How Hollywood Made A Monster" also discusses the history of censorship and the objectionable images, identifying two other moments that were censored in some areas: a close-up shot of a needle injection and the Creature's look of horror when Fritz waves a torch in his face.

Frankenstein

Eventually, "Frankenstein" was restored — but from 1938 until 1985, viewers saw the censored version. This is important because the movie went through a bit of a renaissance in the late-1950s and into the 1960s, thanks to Universal releasing it as part of a TV syndication package. Many, many people alive today first discovered the horror movie on TV late at night, and were only able to see it in its full glory — as James Whale intended — literally decades later.

The censorship "Frankenstein" faced is actually somewhat notorious in classic horror historian circles — not only because of what it meant for the movie itself, but also because it had a big impact on cultural attitudes towards film censorship at the time. Curtis notes that the reports of "31 cuts" by the Kansas board stirred up "anti-censorship" sentiments in Hollywood, and Horton argues that Whale's film "galvanized a chaotic censorship crisis going on in Britain." Movies were still such a new thing in the 1930s, and as Gregory D. Black details in his book "Hollywood Censored," this was a time of moral panic about the medium's influence. The idea that art has the power to corrupt was nothing new — look at Oscar Wilde's "The Picture of Dorian Gray" — so it's not really a surprise that there was pressure on Hollywood to self-censor.

The PCA was a reaction to these social fears — and to be blunt, cracking down on objectionable content was good for business. Thankfully though, we've moved beyond this vein of thinking, and filmmakers today enjoy much more freedom to create daring, thought-provoking movies.