How Clint Eastwood Saved The Bridges Of Madison County From Production Limbo

As a filmmaker, Clint Eastwood is neither precious nor patient. Though the movies he directs tend to unfold at an unhurried pace, he zips through production, bringing them in ahead of schedule and under budget. He crews and casts with an eye toward proficiency and authenticity. When an actor steps in front of his camera, they know precisely what's expected of them. Hit your mark. Speak the line as written. Be real. One or two takes, and he's moving on to the next setup.

In 1994, Eastwood did not seem like the ideal choice to direct Robert James Waller's bestselling romantic novella "The Bridges of Madison County," but his notorious impatience and preference for simplicity was just what the material needed.

Eastwood was peaking as an artist. After the mean-spirited disaster of 1991's "The Rookie," he'd gone back to basics as a storyteller and turned his focus inward. Though he'd been examining his iconography since 1985's "Pale Rider," the films on which he was riffing (Leone's "Dollars" Trilogy and the "Dirty Harry" series) were too fresh in memory. He was also still myth-making, what with one more Dirty Harry movie — 1988's "The Dead Pool," which plays like parody – left in the chamber. But after missing the mark creatively and commercially on his next four features ("Bird," "Pink Cadillac," "White Hunter, Black Heart" and "The Rookie"), Eastwood had to cut the BS and level with himself as a man and an artist. This brought us two spare, soulful masterpieces in "Unforgiven" and "A Perfect World," and Wolfgang Petersen's taut, surprisingly sentimental action blockbuster "In the Line of Fire." While Eastwood the icon might've felt like a poor fit for a weepy vacation read, the man who'd made those last three movies was deep in the pocket for it.

The screenwriter carousel of Madison County

Eastwood was connecting to something shifting in the world and himself. He wasn't a Baby Boomer, but many of his fans were, and they were stirred by his autumnal musings. With era-defining musicians like Neil Young ("Harvest Moon"), Paul Simon ("The Rhythm of the Saints") and Don Henley ("The End of the Innocence") leaning into the melancholy of middle age and beyond, Eastwood should've been at the top of the list to capture the what-if ache of "The Bridges of Madison County" — if only because his notorious impatience would've spared the studio years of development woes.

When Steven Spielberg optioned the novella prior to its publication in 1991, his first choice to direct was Sydney Pollack. On paper, landing the director of "The Way We Were" looked like a coup (especially because that film's star, Robert Redford, had been tipped to play the tale's aging bachelor, Robert Kincaid), but screenwriter Kurt Luedtke, who'd won a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for Pollack's "Out of Africa," couldn't crack the material. Oscar-winning "Rain Man" scenarist Ron Bass was the next man up, and he failed to deliver as well. The project was stalled until Richard LaGravenese, a hot Hollywood commodity on the strength of "The Fisher King" and "The Ref," turned in a draft that hit the right, heartbreaking notes. This was the version that hooked Eastwood (to the delight of Spielberg, who'd always wanted him for the male lead). Alas, when Bruce Beresford became attached to direct, his "Driving Miss Daisy" screenwriter, Alfred Uhry, fouled up everything that Eastwood liked about the previous draft. The project was on the brink of consignment to development hell.

Clint gets what Clint wants

According to a 1995 Entertainment Weekly article by Anne Thompson, Eastwood's extremely limited patience had worn thin, and he let Warner Bros chairman Terry Semel know it. "You guys have blown enough time," he said. "Everyone is going to move on to something else." Eastwood had more than a little leverage. The novella had been at or near the top of The New York Times' bestseller list for two years. This film was getting made one way or the other, and he likely knew Semel couldn't bear the thought of chasing off one of his studio's biggest names. So the exec finally did what he should've done all along: he asked Eastwood to direct it. Eastwood, never one to dally, asked for 24 hours to make his decision.

Eastwood, as ever, was a man of his word. He promptly flew to the film's Winterset, Iowa location, slashed $1.5 million out of the budget by kiboshing a plan to build a new covered bridge, and took the gig. He also insisted on Meryl Streep for the lead role of love-lorn Italian war bride Francesca Johnson (the author wanted Isabella Rosselini, while the studio had been advocating for the likes of Susan Sarandon, Anjelica Huston, Jessica Lange, Cher and Mary McDonnell). Eastwood got everything he wanted, and plunged into production. To the surprise of no one, he wrapped principal photography 10 days ahead of schedule, and came in well under budget.

A publishing phenomenon turned modest box-office hit

"The Bridges of Madison County" ambled into theaters on June 2, 1995, and opened to a respectable $10.5 million at the U.S. box office. The reviews were good. A few were rapturous. Though the negative notices heaped scorn on Waller's novella, they generally acknowledged that Eastwood had elevated the work by throwing out its painfully florid dialogue. With a solid "A-" Cinemascore, it appeared the film would play all summer. It didn't.

The film closed its theatrical run with a $71 million domestic gross, which was perfectly acceptable given Eastwood's budgetary thrift, but a tad disappointing considering that it was based on a publishing phenomenon. Though Meryl Streep earned an Oscar nomination for Best Actress, the movie was otherwise ignored by the Academy. The conventional wisdom was that Eastwood had made a fine picture, but it was still "The Bridges of Madison County." It could only be taken so seriously. The conventional wisdom was wrong.

A rain-swept finale for the ages

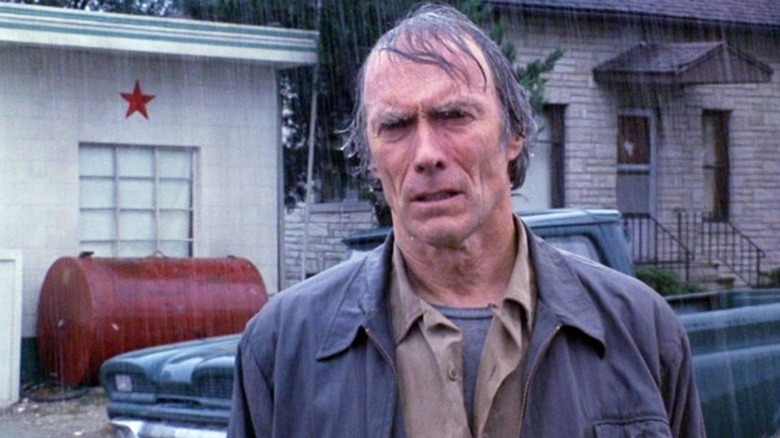

Of Eastwood's post-"Unforgiven" output, "The Bridges of Madison County" stands alongside "A Perfect World" as his most underrated achievement. Free of the hype surrounding its 1995 release, you can sink into its leisurely groove and engage it as a standalone romantic drama that quietly builds to a shattering climax. Though the narrative is bookended so that we know the affair will end after four days, we do not know how close the lovers will come to running away with each other. We have no idea that Francesca will see Kincaid lingering in the middle of a deluge, wordlessly beckoning her to flee the passenger seat of her husband's car and leave her family behind. She remains, but Eastwood lets the scene play out for another beat or two, earning a deep, plaintive sigh from a simple closeup of a left-turn signal.

Would "The Bridges of Madison County" been a bigger hit had Semel let Eastwood walk and opted for an adaptation as schmaltzy as the book, one starring a more conventionally desirable male lead? Perhaps. But then we wouldn't have this work of exquisite, heartrending beauty from a man who'd built his legacy on brutality. Thank god Semel was every bit as impatient as Clint Eastwood.