How Brief Encounter Inspired Sofia Coppola's Lost In Translation

What does Bill Murray whisper in Scarlett Johansson's when "Lost in Translation" comes to an end? There are videos available answering that question for spoiler addicts, but for most of us, we simply don't need to know. It is a private moment between the two as their whirlwind (but very discreet) relationship comes to an end.

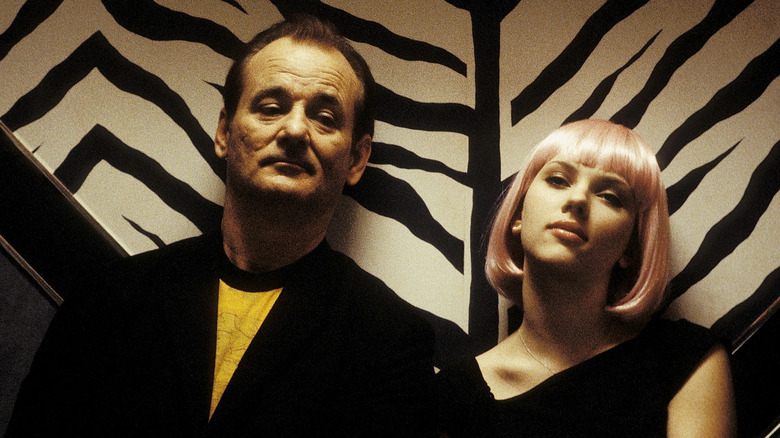

Murray plays Bob Harris, a discontent middle-aged Hollywood star who is in Tokyo to film a commercial for Suntory whisky. Johansson is Charlotte, a young wife fresh out of college wondering what to do with herself while her husband (Giovanni Ribisi) is off photographing celebrities. Both adrift in the buzzing metropolis, they at first find solace in one another before feeling what may be the first sparks of romance.

Sofia Coppola's dreamy film captures the feeling of being a foreigner in a strange land better than any other movie I've seen. While some of the culture-shock comedy ("Lip my stockings!") hasn't aged well, it gets right that disorienting but exhilarating sense of trying to keep your head above water while swimming upstream. It's a common feeling when living abroad, and you occasionally find unlikely kinship with another foreigner who you might never have come into contact with under ordinary circumstances.

Coppola successfully skirts the potential ickiness of the glaring age gap between her two stars by keeping Bob and Charlotte's budding romance chaste and understated, with their growing feelings communicated largely wordlessly through body language and meaningful glances. "Lost in Translation" has become one of the most popular unrequited love stories in modern cinema, with Coppola taking inspiration from the greatest of them all: David Lean's "Brief Encounter."

So what happens in Brief Encounter?

"Brief Encounter" tells the tale of Laura (Celia Johnson), a middle-class housewife married to a dull but affable chap named Fred (Cyril Raymond), a man whose idea of a good time is doing a crossword puzzle together. On her way home from her weekly trip into town, she gets a little soot in her eye at the railway station. In swoops a dashing doctor, Alec (Trevor Howard), a General Practitioner who is also married with children.

Laura keeps bumping into Alec in the following weeks, and their friendship begins innocently enough with a visit to the afternoon matinee. Soon, over cups of tea and trips to the countryside, they realize that they are falling in love with each other. Laura increasingly feels the need to lie to cover up their meetings, and things come to a head when Alec borrows his friend's apartment so they can have some private time together. This goes wrong when his friend returns home unexpectedly and chastizes Alec while Laura is left wandering the streets in shame before her next train home.

They both understand that their duties are to their spouses and children, and things must come to an end. Alec announces that he is taking a job in South Africa, and their brief encounter will soon be over almost before it has begun.

"Brief Encounter" is one of my mum's favorite movies, and it makes her cry every time. I saw it dozens of times growing up and it always gets me, too. I usually spend the first 10 minutes thinking, "This is it. This is the time when it's just too old-fashioned, plummy and class-bound for me." But then at some point that I'm still unable to define, I get hooked, and I'm choking back the tears by the end.

Does Brief Encounter hold up?

Even almost 80 years on, "Brief Encounter" remains one of Britain's best-loved films. It's one of those movies that people just know, through cultural osmosis, so they get the references even if they haven't actually seen the film itself. As of 2015, roughly 50,000 people a year were still visiting the refreshment room at Carnforth Station in Lancashire, which doubled for Milford Station in the film, and the station clock was the second most photographed timepiece in the country, just behind Big Ben (via BBC).

It looks really twee and dated compared to "Casablanca," released three years earlier in 1942. Its cozy and parochial nature is emphasized by the pre-war setting, a world that had ceased to exist by the time it hit theaters just a few months after World War II, which must have added extra poignancy for so many audience members.

Unlike "Casablanca," which is very cosmopolitan and worldly, Laura and Alec are bound by the moral code and class conventions of the time, with the need to keep up appearances and maintain their respectability. Meanwhile, the working-class train station employees freely flirt and discuss their affairs quite openly without any shame.

While the accents and the manners and the settings are initially off-putting, the themes of "Brief Encounter" remain universal. The performances are superb, especially Johnson; we're really drawn into her feelings and dilemmas through her voice over. The writing is excellent, adapted by Noel Coward from his own play, "Still Life," and the dialogue is so crisp, once you get past the plummy voices. While Laura and Alec try their best to repress their feelings, the language becomes increasingly melodramatic, hand-in-hand with the stormy passions of Rachmaninoff's "2nd Piano Concerto," which builds as a dramatic counterpoint to the buttoned-up romance.

We must also mention David Lean. If you come to "Brief Encounter" via his grand epics, there might be an assumption that smaller means simpler, but Lean's work is more impressive on an intimate scale like this, teasing out every nuance and downcast glance from his actors while making the most of Robert Krasker's evocative photography. Then there is that quietly daring circular narrative, a common ploy nowadays but fairly unusual for its time. It works beautifully, first drawing us into the confidence of the tentative lovers then, when we loop back, making us painfully aware of their last few moments together slipping away.

Was Brief Encounter controversial at the time?

This is a more complicated question than you might think. "Brief Encounter" came out just nine years after King Edward VIII abdicated from the throne to marry Wallis Simpson, a divorced American woman. Marriage was widely respected and infidelity was definitely frowned upon more than today, coming across very strongly in the scene where Alec's smarmy friend busts them alone in his flat and gives Alec a thorough dressing down. It was also banned in Ireland for portraying "numerous seductive and indelicate situations" (via Irish Times), and it wouldn't see the inside of an Irish movie house for another 17 years.

Back in the UK, the situation was more nuanced. While the moral values that Laura and Alec just about manage to cling to were still prevalent, things were different during the wartime period. As historian Matthew Sweet observed (via BBC):

"Many of the rules were off as far as fidelity and relationships were concerned. If you were living your life in the shadow of the V2s and in the shadow of the Blitz then you were going to behave as if there was no tomorrow because it was quite likely that there wouldn't be. So in the war, there's a big upsurge in marital infidelity and in affairs."

On the face of itm "Brief Encounter" is very stiff-upper-lip and middle-class, but it was far more inclusive than it might appear, and audiences were more sympathetic to Laura and Alec for reasons that were not necessarily romantic. The film's final line was especially poignant for viewers at the end of a devastating global conflict. Thomas Dixon, author of "Weeping Britannia," said (via BBC):

"The movie theater in particular was this special place, this special darkened semi-private secret place where one could go to listen to Rachmaninoff and cry one's eyes out... for an audience in 1945 to hear those words, 'Thank you for coming back to me,' there have been terrible separations, perhaps there have been these secret romances, these illicit affairs, heartbreak, heartache, mothers separated from their sons, and so on. And lots of people having these reunions and endings, and coming back together, so those few words... meant an awful lot to an awful lot of people."

Perhaps this is the reason why "Brief Encounter" remains so durably popular with the British public. It was a film that spoke to everyone who had loved and lost, were separated and reunited, during the war years. Those sentiments have been passed down generation to generation in a country whose national identity is still very much influenced by World War II.

Cinematic affairs and the Hays Code

Attitudes towards infidelity and extra-marital affairs have changed significantly since "Brief Encounter" was first released, especially when it comes to how flings are portrayed on-screen. In the United States, the censorious Motion Picture Production Code, aka the Hays Code, decreed:

"The sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld. Pictures shall not infer that low forms of sex relationship are the accepted or common thing."

The Code only seriously came into play in 1934 when an amendment meant films needed submitting for approval by the Production Code Agency (PCA). Under the Code, even a married couple sharing a bed was a forbidden, so extramarital affairs were definitely a no-no. Nevertheless, filmmakers sought ways to skirt these prohibitive doctrines. "Casablanca" won Best Picture despite a huge chunk of its plot revolving around the love affair between a cynical bar owner and a married woman. It avoided the wrath of the censors because Ilsa thought her husband was dead when she first got together with Rick.

Film noir classics like "Double Indemnity" and "The Postman Always Rings Twice" pushed the boundaries further. Fast-forward to the more permissive '60s, and the Code was on its last legs. With controversial films like "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" and "The Graduate" challenging the Code's fitness for purpose it was eventually abolished in 1968. By the time "Brief Encounter" received a remake with Richard Burton and Sophia Loren in 1974, the directors of New Hollywood were regularly making films where infidelity was commonplace, rendering it an irrelevant dinosaur.

How Brief Encounter inspired Lost in Translation

Skip forward another quarter of a century to "Lost in Translation," and the fact that its central characters were both married barely warranted a mention when discussing their liaison. In the modern era, more eyebrows were raised about their age disparity. Hollywood's tendency to cast aging leading men with much younger love interests is a long-standing issue going back decades. This has come under particular scrutiny in recent years with many articles devoted to the subject. There have also been parallel conversations about the socially acceptable age difference for romantic partners for regular folk too, with the "Rule of Seven" touted as an easy way to figure out what is creepy or not.

"Lost in Translation" doesn't dwell too much on the wildly disparate ages of Bob and Charlotte, but it could play into why their relationship is fated to remain a holiday romance. They might stand out as conspicuously foreign in Tokyo, but the expat bubble also affords them a certain degree of anonymity and a break from regular standards that apply back in the real world. In that environment, they can masquerade as two like-minded foreigners hanging out in unusual circumstances. But back home their age gap would likely cause problems. Perhaps part of the reason "Lost in Translation" doesn't seem completely egregious, despite the 34-year age difference between middle-aged Murray and a very young Johansson, is the tasteful and sincere way Coppola handles it.

Coppola was writing from experience having spent time in Tokyo during her twenties, and she took her cue from "Brief Encounter" when making their relationship meaningful but pointedly chaste. She said (via NME):

"It was a big inspiration for me when I was writing "Lost in Translation." Just the intense emotion between these two characters. Very little is said, and you feel so much in just a gesture of a pause. It's so emotional but everything's under the surface. Maybe that's very English? But I love that."

Unlike Laura and Alec in "Brief Encounter," who are of a similar age, I never got the sense that Bob and Charlotte ever think that their relationship could progress beyond what they share together in Japan. They get what they need from each other at very uncertain times in their lives and, to paraphrase that other great '40s tale of tearful goodbyes, they will always have Tokyo.