Hayao Miyazaki Had Conflicted Feelings About Anime's Growing Audience

Japanese anime was first seen in the United States in the 1960s with shows like "Gigantor" and "Astro Boy" and "Speed Racer," grew in cult appeal throughout the 1970s, and hit it big cinematically in 1985 with the release of "Akira." Throughout the 1980s, more and more anime crept its way into the fringes of popular culture, with an increasing number of imports making their way into the collections of enterprising nerds. When "Pokémon" hit in 1997, the floodgates opened, and anime was officially mainstream. In 2022, one cannot browse through any streaming service without encountering hundreds of Japanese shows — with dubbing or subtitles as options — ready for mass consumption. Indeed there is at least one notable streaming service, Crunchyroll, devoted to the medium.

However, as with anything that once possessed mere cult or outsider appeal and then becomes mainstream, a pang was felt by old-world nerds who preferred remaining in the shadows. This is an attitude that, of all people, Hayao Miyazaki — the director of "My Neighbor Totoro," "Spirited Away," "The Wind Rises," and many other excellent animated feature films — once expressed. In a 1994 interview with Yom magazine, Miyazaki admitted that anime's popularity was a threat to his creative freedom.

Necessity is the mother of invention

In the Yom interview, Miyazaki was concerned that live-action films for grown-up audiences were more financially successful. He seemed to long for a media landscape where adult entertainment garnered the lion's share of attention, allowing him to hide in anime obscurity, working for the purity of it, rather than just for the money. Having worked in the industry for years, and seeing what kind of artistic output he could create both with and without money, Miyazaki had the wisdom to know which made for better movies. In short, Miyazaki, in 1994, believed in the purity of not "selling out":

"I wish movies for adults were doing better. I wish such things as ticket sales or movie awards would go on without involving anime. It would be better if anime lives in a corner of the movie world, and people say 'oh, there is also anime.' If so, I don't have to do interviews or lectures. If so, directors and animators, all can work pure and poor, remaining anonymous, just because we want to do the job we can satisfy ourselves. It used to center around what we made, and we could work only by our internal values such as what we learned in this work, if we made progress, or if we could foster [animators]."

This sentiment was common all over the world in the 1990s, which can be reflected in the music of the era. This was the decade wherein Kurt Cobain wore a "corporate rock still sucks" T-shirt, and characters in Gen-X films like "Reality Bites" and shows like "Rent" were concerned about making art outside of a media-saturated, ultra-commercial environ. While Miyazaki is not an American Gen-Xer — he was born in 1941 in Bunkyo — his concerns about art were very much the same. Miyazaki was even nostalgic for his time as a struggling artist, longing intensely for a time when artistic freedom was more common:

"I experienced that era. Seeing from that experience, I feel although anime is in the limelight, or because of it, things are more difficult now."

Movies for children

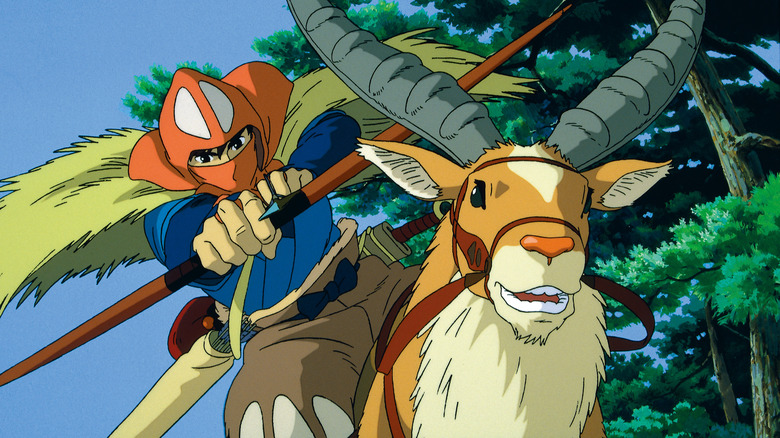

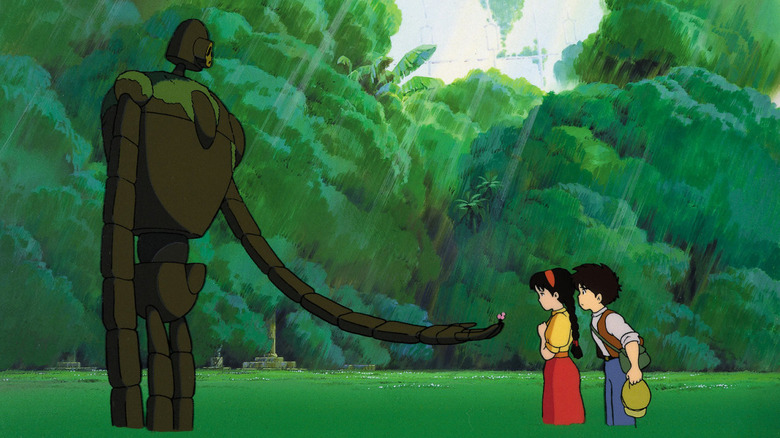

His 1984 film "Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind" and his 1997 film "Princess Mononoke" notwithstanding, Miyazaki has typically made gentle films that exist in quiet, domestic idylls. His movies are mostly appropriate for young audiences, and seek to depict an honest version of a young child's experience. It's notable that the center of his film "My Neighbor Totoro" is actually the background stress two young girls feel in regards to an ailing mother in a hospital; the giant furry fantasy creatures are secondary. According to the Yom interview, Miyazaki said that anime has to be for children, likely. Even in the 1994 Yom interview, 20 years prior to the above meme, he was concerned that Japanese animators were losing connection with real-world children:

"I still think anime has to be made for children. But, our situation changes, and I myself change. While saying 'we should make it for children,' I find myself making a film which is not for children."

That was in 1994. It's notable that he was working on "Princess Mononoke" at the time. Years later, in 2002, after the release of "Spirited Away," Miyazaki was asked again if he still felt the same way in an interview with Midnight Eye. He was stalwart:

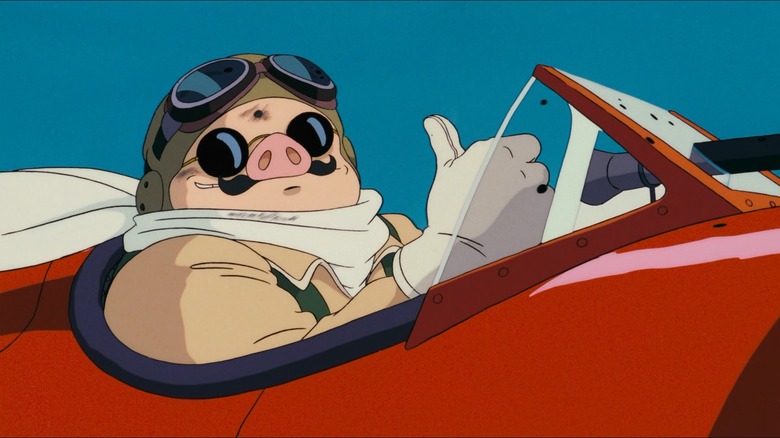

"I never said that 'Porco Rosso' is a film for children, I don't think it is. But apart from 'Porco Rosso,' all my films have been made primarily for children. There are many other people who are capable of making films for adults, so I'll leave that up to them and concentrate on the children."

When asked how he feels about the adults who take a great deal of edification from his movies, Miyazaki was flattered, but remained steadfast. Movies for kids — honest ones about actual children — have more possibilities. It's clear that Miyazaki values emotional honesty, and he feels that children, having not yet developed a carapace of cynicism, have more opportunities to restart their lives, rework their viewpoint, and continue to grow. Accurately capturing the real world of kids — as opposed the unchanging adult world informed by media — was vital to this.

That meme

Those paying attention to internet memes in 2014 might recall a circulated image of Miyazaki emblazoned with the subtitle "Anime was a mistake. It's nothing but trash." The subtitle was revealed to have been faked, but the image did come from a 2014 interview with The Golden Times wherein Miyazaki felt that a lot of anime was become far too fan-oriented. While sketching a young girl, Miyazaki pointed out that he was attempting to capture how a child actually moves while flapping her arms. He argued that one can only animate well if an animator spends time watching actual people. A "fake" version of people was too large a part of modern anime. In short, Miyazaki feels that trends in anime were tipping far too deeply into the world of stylized art.

"You see, whether you can draw like this or not, being able to think up this kind of design, it depends on whether or not you can say to yourself, 'Oh, yeah, girls like this exist in real life.' If you don't spend time watching real people, you can't do this, because you've never seen it."

Pressing back against the passions of fandom can be a dangerous proposition, and Miyazaki raised some hackles in lambasting otaku (a neighboring words to "geek" or "fanboy," but with a hint of "detrimentally socially awkward" hidden inside), whom he implied weren't interested in the real world. Miyazaki wasn't so much lashing out against fan communities, though, as he was pointing out that modern Japanese animators were too often influenced by their own consumption of media, and too infrequently influenced by the actual world:

"Some people spend their lives interested only in themselves. Almost all Japanese animation is produced with hardly any basis taken from observing real people, you know. It's produced by humans who can't stand looking at other humans. And that's why the industry is full of otaku!"

The balance between the imaginary and the virtual

Miyazaki also wanted to stress the importance of telling stories for children that employ fantasy elements properly; he is not interested in creating an escape into a tech-based world, but to enhance the world with imagination. From Midnight Eye:

"I believe that fantasy in the meaning of imagination is very important. We shouldn't stick too close to everyday reality but give room to the reality of the heart, of the mind, and of the imagination. Those things can help us in life. But we have to be cautious in using this word fantasy. In Japan, the word fantasy these days is applied to everything from TV shows to video games, like virtual reality. But virtual reality is a denial of reality. We need to be open to the powers of imagination, which brings something useful to reality. Virtual reality can imprison people. It's a dilemma I struggle with in my work, that balance between imaginary worlds and virtual worlds."

Miyazaki, now 81, is still directing. His next film, due in 2023, will be called "How Do You Live?" What a fitting question for Miyazaki to ask modern animators as well as modern audiences. Are you living for fantasy, losing yourself in media, or are you living in the real world?