There's One Idea Bong Joon-Ho Can't Keep Out Of His Films

Korean filmmaker Bong Joon-Ho has mastered every genre from sci-fi to murder mystery, but one subtle common thread runs through all of his work. One theme he established in his breakout crime drama "Memories of Murder" (2003) can be found even in his most recent work, "Parasite," made nearly two decades later.

Bong explained in an interview with The Atlantic that his films are founded in "misunderstanding." "The audience is the one who knows more, and the characters have a difficult time communicating with each other," Bong goes on. The director uses this technique to derive sympathy from the audience. Seeing a character act on what the audience knows to be misinformation makes them "feel bad." Bong believes that confusion drives conflict more strongly than an antagonist does, pointing out that there are no villains in "Parasite," but that instead the characters "end up hurting each other" based on their misconceptions.

Crossed wires are Bong's bread and butter

"Parasite" certainly follows this logic to a tee, with many characters acting under false impressions for much of the film. Through a string of personal recommendations and other small schemes, the impoverished Kim family convinces the wealthy Park family that they are a set of unrelated and qualified workers. They soon discover that the previous housekeeper had a huge secret herself — she was hiding her husband, on the run from gambling debt, underneath the house. It all ends in tragedy when (spoiler alert) the old housekeeper is accidentally killed and her husband springs loose from the basement to take his revenge on the Kim family. In this film, the most tragic moment is born from a misconception that the housekeeper's husband has about the Kim family.

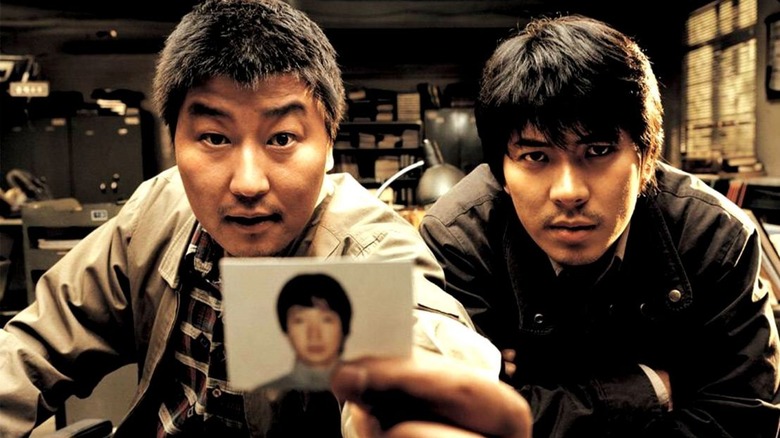

Bong's sophomore film "Memories of Murder" was extremely different from "Parasite" in subject matter, but its central conflict also rested on three characters being misinformed about one another. Detectives Park, Cho, and Seo butt heads over how best to investigate a murder, and their competing methods lead them to overlook the evidence in front of them. This conflict ultimately keeps them from solving the case and achieving their collective goal. The audience is sympathetic to all three of them and therefore doubly frustrated at their inability to put aside their differences and work together.

The director has Hitchockian methods

Bong's filmmaking technique closely resembles Hitchcock, who described a very similar scenario in his formula for suspense. Describing the technique in "Hitchcock/Truffaut," Hitchcock famously proposed the scenario of a bomb under a table in a film. If the audience isn't aware of the bomb prior to its explosion, they are surprised when it goes off, but the preceding moments are "of no special consequence." If the audience is aware of the bomb before the explosion, "this same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the secret."

The secrets that the characters and viewers keep from one another in Bong's films obviously take direction from Hitchcock, and Bong is not shy about citing the master of suspense as a major artistic influence. He has seen "Psycho," Hitchcock's ground-breaking 1960 horror film, "more than fifty times" (via Collider). Like Hitchcock, Bong doesn't shoot coverage and sticks closely to his storyboards. John Hurt called his filmmaking style "Hitchcockian" on the set of "Snowpiercer," which Bong said he was "very grateful to hear."

Masters take influence from masters, and just like Hitchcock before him, Bong has a distinctive style that permeates through his diverse filmography. Bong's misconceptions are not identical to Hitchcock's formula of suspense — the filmmaker undeniably adds his own twist — but even Bong wouldn't deny that they have the old man's fingerprints all over them.