Slow Cinema To Quicken The Heart: The Films Of Tsai Ming-Liang

"Slow cinema" isn't so much a movement as it is a style. As the name implies, Slow cinema is characterized by long, extended shots, often without music or dialogue, wherein the camera rests, simply observing for minutes at a time. Perhaps it will be a slow tracking shot of a muddy Eastern European farm, as in the works of Bela Tarr. Perhaps it will be a penetrating closeup of a suffering young man as in Hu Bo's "An Elephant Sitting Still." Perhaps it will be a shot of a remote Filipino jungle, trees whipping in the wind, with a human character barely perceptible in the corner as in the works of Lav Diaz. Perhaps it is a slow trudge through a weird landscape as in the films of Andrei Tarkovsky. Perhaps we're scanning the screen for the supernatural as in the works of Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

Slow cinema is often called by critics an antidote to modern filmmaking. In deliberately eschewing incident, slow cinema seeks not to overstimulate with such trifling traditions as story and plot, but slow down the viewer, lull them, push them into their seats with shots that can be either calming and contemplative (Weerasethakul) or a downright confrontational struggle (Hu Bo). It is only when you are slowed that your mind can truly, achingly, open.

The first shot of Tsai Ming-liang's most recent film, 2020's "Days," is a single, static take of the film's lead character (Tsai regular Lee Kang-sheng) sitting in a chair, staring out at the rain. He is stone-faced. He listens to the falling water. There is no music. He does not move and he does not speak. The shot lasts eight full minutes. Later in "Days," the film's other character (Anong Houngheuangsy) will be seen in his kitchen preparing vegetables. He will say nothing and do nothing beyond his chore. That shot also lasts somewhere in the range of eight minutes. "Days" will later feature a long shot of a character sleeping in bed.

The long takes in "Days" serve a vital function, communicating to the audience an outsized loneliness that dialogue and action could not. The centerpiece of "Days" is a hotel meeting between the two men mentioned, also depicted in a long take. Without speaking, they engage in a tryst that starts out with mere touch and turns into something very sexual. Two people connecting, reaching through their isolation, finding release, solace, a desperate touch from another person. After their hookup, one presents to the other a small music box. A memento. Then another long shot, from across the street, of the two men sharing dinner. Then they recede from each other, back into loneliness and isolation. It is glorious.

Rebels of the Neon God

Allow me to introduce you to Malaysian-Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-liang. Tsai is one of the masters of modern slow cinema, and his movies all use pacing, silence, and distance between characters to explore what he clearly feels is the central plague of the modern world: an inability to connect. In many of Tsai's films, queer characters — sometimes just discovering their nascent sexuality, as perhaps happens in his 1992 debut "Rebels of the Neon God" — look to connect with other men, but are stymied by being forced into the closet by the world around them. Tsai has made 11 features in his career, three documentaries, and multiple shorts and TV movies besides.

Tsai's films typically take place in rundown, aggressively drab urban interiors where beauty does not live. Apartments in Tsai films are often flooded, damp, spare, mildewy. You can smell the hallways and bathrooms in his movies. And yet, there is an undeniably cinematic quality to Tsai's run-down, low-rent interiors and deliberate lack of flash. Tsai seeks nothing less than ecstatic truth with his camera, using the four sides of the screen to cage in his protagonists as they drift, drift from one wistful scenario to the next. It's exhilarating.

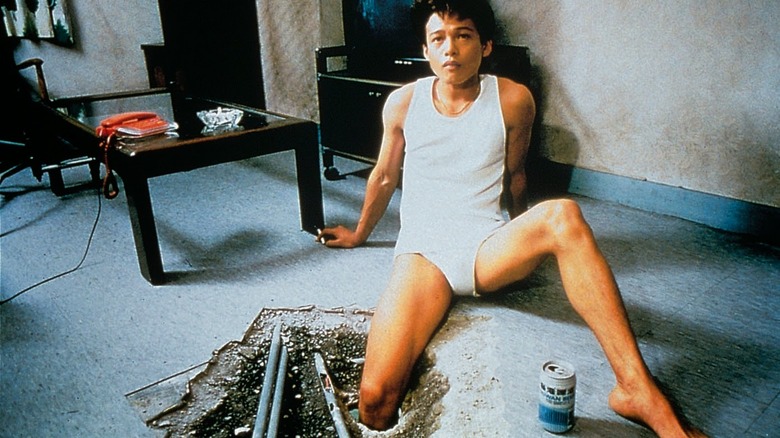

"Neon God" is perhaps Tsai's most incidental film, following a trio of teenage punks and a young man (Lee) who more or less talks them. The Lee character clearly longs for the carefree lives they live, as he has been studying at cram school, and sees no future for himself there. Indeed, he drops out of school partway through the movie. It could be said that Lee is in love with the leader of the punks (Chen Chao-jung), something that is confirmed when Lee goes to a telephone dating service and cannot bring himself to talk to the women on the other end of the line.

A lot of "Neon God" takes place in tiny hotel rooms, and a 1992-era video arcade, giving glorious, dust-scented flashbacks to this old Gen-Xer. The hallways inside the arcade, the torn upholstery, the damp shirts. Watching "Neon God" is a tactile experience.

The Hole

There is a temptation to stage slow cinema as something removed from time. That, in slowing down the pace, filmmakers are delving into something universal about human consciousness. While that does tend to be the effect of slow cinema, it is not a thesis, and Tsai does bandy about with the fantastical, the whimsical, and the political.

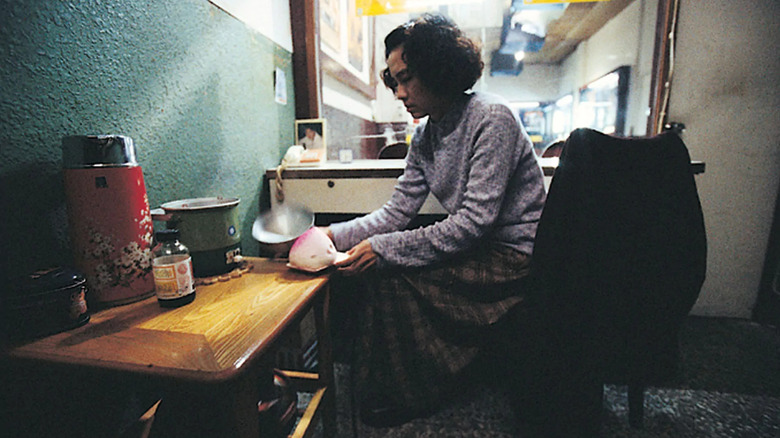

His 1998 film "The Hole" was produced as part of an international series of films called "2000, Seen By..." all about millennial angst (also included in the series was Hal Hartley's "The Book of Life," and Don McKellar's "Last Night"). It's difficult to describe the chill in the air at the end of the 1990s for those who weren't there to experience it, but for many it really did feel like the end of history. Apart from fears about the Y2K computer virus, there was a sense of being adrift in the world, no future ahead. That nothing interesting could happen once 1999 ended. It was an apocalyptic philosophy that inspired frustration and release. "The Hole" envisions a 2000 where people have been infected with a curious virus that causes them to hide in small, dark spaces like rats. The parallel between "The Hole" and worldwide Covid lockdowns should immediately be recognizable.

The title refers to a hole in the floor of the apartment occupied by Hsiao Kang (Lee again), a small aperture that offers the only connection either he or the woman who lives below him (Yang Kuei-mei) have to another human being. "The Hole" is Tsai at his silliest, featuring musical numbers, fantasy sequences, and multiple little titters throughout. But all without ever leaving Tsai's trademark aesthetic of flooded apartments, ghastly interiors, and long, still shots.

Goodbye, Dragon Inn

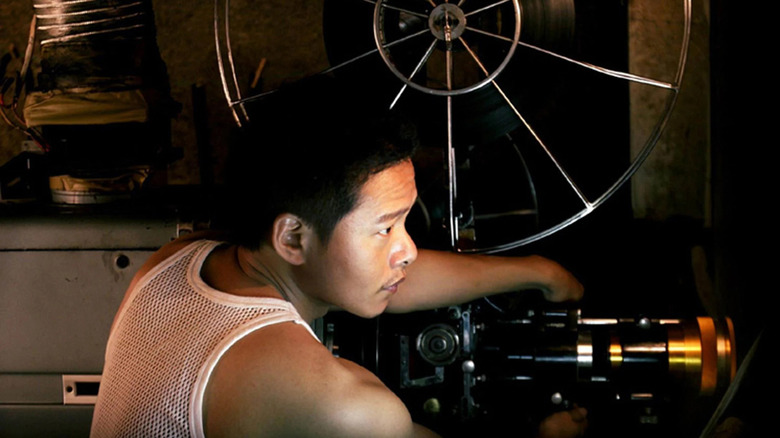

Tsai's best film — and handily one of the best films of the '00s — is probably "Goodbye, Dragon Inn," a requiem to cinema in general. Perhaps carrying over his millennial angst from "The Hole," "Goodbye" takes place in a vast, gym-like movie palace in Taipei during the last few hours of its operation before closing forever. The cinema is screening King Hu's 1967 wuxia classic "Dragon Inn" to a barely populated theater. Like most of Tsai's interiors, this theater is rundown, dusty, caked with memories that need to be scraped off and disposed of. Over the course of the film, we sill see the theater's projection booth, the box office, the isolated places where cinema is created on a ground level. We'll see a young hustler feeling out whether or not another patron might want to hook up with him. We'll hear a story that the theater may be haunted. Note: All theaters are haunted.

And, by the film's end, several actors from "Dragon Inn," playing themselves, will meet in the lobby to more or less shut the book on cinema altogether.

Despite the elegiac quality of "Goodbye," it is just as peaceful and glorious as it is sad. It possesses the thrill of staying at a theater after hours, gazing upon the living bones of film itself. After all, we consume cinema in public places, sometimes rundown, personal, neighborhood joints that fade out and disappear with little fanfare. There is a romance to cinema in how unromantic its presentation is.

And that's the crux of Tsai Ming-liang. He is a romantic who longs for human connection in a world of drabness, damp, and isolation. The modern world, Tsai seems to be saying, may be the most boring place ever, crammed as it is with casual neglect and obstructions between people, but connection can and will be made. There will be a moment of music, a film to watch, an embrace, a dangled leg that will always bring us back together.

Where can I find Tsai Ming-liang movies?

Because of the bizarre caprices of international distribution, Tsai's films are a bit scattered on streaming services. "Goodbye, Dragon Inn" can be seen with a subscription to the Metrograph streaming service.

The oft-reliable Ovid has "The Hole" and "Rebels of the Neon God." Kanopy and Mubi have "Neon God" as well, along with Tsai's film "Stray Dog." His 1995 film "Vivre L'Amour" can be rented on Apple TV, but only on Apple TV. A streaming service called Filmbox+ has his 1996 film "The River," and, oddly, it's Redbox — that last bastion of low-budget action DVDs found outside your local 7-Eleven — that has his 2014 film "Journey to the West."

"Days" can be rented on Amazon.

Tsai Ming-liang is celebrated by the lucky souls who have sought out his work, and, dear readers, searching for him will only prove rewarding. Then you can reach out, make connections, and touch those who have been moved by his slow, quiet, challenging art.

Damn, what good movies.