Bill Murray's Groundhog Day Casting Gave Its Creator Cause For Concern

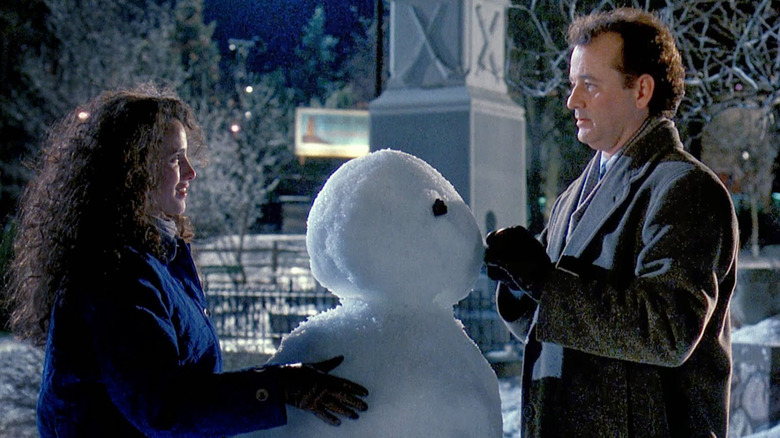

A fun idea: Columbia Pictures ought to announce a remake of Harold Ramis' 1993 comedy "Groundhog Day." In press releases, the studio should boast that they will have returning legacy characters from the original. In fact, the press releases should read, most of the original cast will be returning. Bill Murray and Andie MacDowell can tour the press circuit, giving interviews and talking about how great it will be to revisit a similar story. Then, when opening day arrives, surprise! It's merely a rerelease of the original.

The premise of "Groundhog Day" is familiar to most modern audiences. The story's protagonist wakes up one morning to find themselves repeating the previous day a second time. The next morning, the same thing happens. They, and they alone, are caught in a time loop. This is a conceit that was used in at least one episode of "The Twilight Zone," was employed in Jack Sholder's "12:01," and has been having a miniature renaissance thanks to "Happy Death Day," "Palm Springs," "The Map of Tiny Perfect Things," and many others besides.

The screenplay for "Groundhog Day" was originally written by Danny Rubin, who would go on to pen the thriller "Hear No Evil," also in 1993, and the punk rock middle finger film "S.F.W." in 1994. At some point during pre-production on "Groundhog," Rubin was offered a choice: He could have as large a budget at the film required with Harold Ramis directing and no creative control, or he could make the movie for a mere $3 million and have as much creative control as he wanted. Rubin selected the former path, turning his script over to Ramis and hoping for the best. He was immediately filled with trepidation.

It's a comedy now

As with any script relinquished to a studio, rewrites and changes were put into play almost immediately. Rubin's original concept was meant to be sadder and a bit headier, whereas Columbia wanted a broad comedy. Harold Ramis saw what Danny Rubin was afraid of, heard what the studio demanded, and attempted to rework Rubin's script in a way that could placate them both. In a 1993 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Ramis declared that he rejected notions of bland sentimentality and "cornballism," trying to make "Groundhog Day" into something funny, yes, but also legitimately thoughtful with a healthy streak of cynicism.

That process was harrowing for Rubin, who was constantly afraid of his story being turned into a farce. In an oral history printed in the New York Times in 2017, Rubin admitted his suspicions:

"When I heard Harold had cast Bill, my thinking was, 'Oh, they're not taking my movie seriously.' I was already 30, and the films Harold and Bill had made together were for younger people — sort of adolescent, popcorn-chomping Saturday-afternoon comedy. Everyone around me was excited for me. I was just skeptical."

According to a 2004 Harold Ramis interview in The New Yorker, the original tone was more akin to a morality lesson. In a philosophical sense, this was the logical approach. Rubin appears to have been inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche's theory of eternal recurrence, wherein the philosopher challenged readers to picture no afterlife, but the life they currently are living as repeating infinitely exactly as it is now. Would you change your actions and moral stance if you knew it would have to be repeated instead of rewarded in heaven? "Groundhog Day" was to contain narration from the main character and started after he had already been trapped in a time loop. Ramis reworked all that. At first, Ramis and Rubin worked on a new draft, wanting to make the lead character's arc more akin to the stages of grief than a traditional comedy. Ramis ended up writing the final draft alone, and the two would share screenwriting credit.

Bill Murray doing Bill Murray stuff

In the New York Times' oral history, producer Trevor Albert tells an amusing story about how Bill Murray came on board "Groundhog Day." Despite Danny Rubin's apprehension, Murray was to be a huge "get," and he seems to have known that. Albert reveals the bizarre way Murray agreed to the role:

"Bill's reaction was positive, but he is whimsical and challenging. He came into our office in L.A. to talk about it. He got up and said, 'Guys, walk with me.' We walked out to the parking lot, and he got into his Maserati. He started the engine and slowly started to drive away. He finally said, 'O.K., I want to do it,' then drove off into the night."

Rubin's original vision may have been darker with a more moralistic bent, but the final film was overwhelmingly well-received by audiences and generally liked by critics upon its initial release (though Gene Siskel, cementing Rubin's fears, found the film to be too saccharine). Rubin's and Ramis' screenplay ended up winning an award at the New York Film Critics Circle that year. Curiously, it tied with Steven Spielberg's Holocaust drama "Schindler's List." The years, however, have been kind to "Groundhog Day," and some have included it on lists of the greatest films ever made.

Rubin's vision was altered, but the screenplay he shared with Ramis is widely beloved. Plus he co-wrote "S.F.W.," a gloriously angry film, so Rubin is sitting pretty.