At 75, Black Narcissus Is Still A Work Of Stunning Visuals And Rich Psychological Depth

Nine thousand feet in the air may sound like a low-flying plane altitude, but in "Black Narcissus," it's where the nuns go to set up a convent in a wind-swept locale that becomes the setting for a superb, sophisticated psychodrama.

The nuns, led by Deborah Kerr's Sister Clodagh, have sworn yearly vows, rather like contract workers instead of lifelong devotees. Not all of them are cut out for this line of work. Nor is Mopu, the old Indian palace they inhabit, the best fixer-upper for a convent, since it used to be a "house of women," or harem, and there are still murals of bare-chested native women on the wall that would surely qualify as indecent by nun standards.

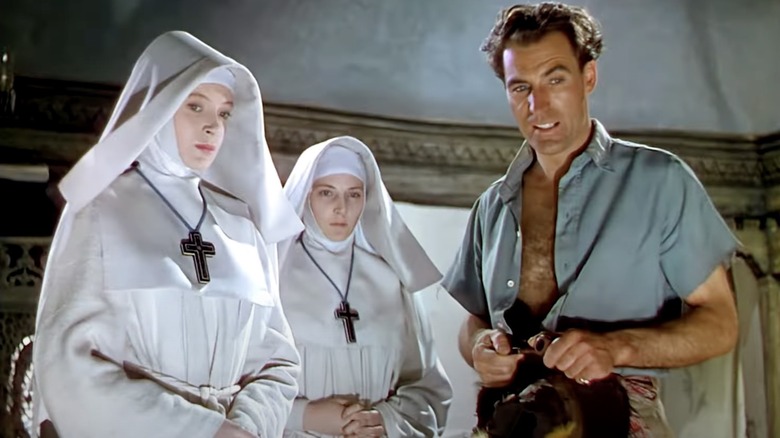

The place holds a strange power to rouse both memories and undercurrents of forbidden desire, driving women mad. "There's something in the air here, it makes everything exaggerated," notes Mr. Dean (David Farrar), the rakish Brit and manly man in short shorts. He serves as their local guide to Mopu and one-third of an unconsummated love triangle with Sister Clodagh and Sister Ruth.

Kathleen Byron plays Sister Ruth and she gives a tour de force performance — which is not a phrase I use lightly. Early on, while ringing the noon bell outside the convent, Sister Ruth looks over the side of a cliff with an impossibly steep drop, and it's as if the movie is giving visual representation to the very mental depths it will explore.

There's some discrepancy about when "Black Narcissus" made its world premiere in vivid, true, glorious Technicolor. IMDb lists the date as April 24, 1947, in London, but a newspaper clipping from an edition of The Guardian seems to indicate that it was on Sunday, May 4, 1947. Either way, "Black Narcissus" is 75 years young now, and if you can't name a favorite movie from the '40s (besides "Casablanca" or "It's a Wonderful Life"), this one should be at the top of your to-view list.

What a difference a place makes

For modern viewers, the bell perch in "Black Narcissus," with its sheer overlook, might recall Tyrion Lannister's sky cell high atop the mountainous Eyrie in the first season of HBO's "Game of Thrones." In late 2020, "Black Narcissus" was also the subject of a less well-received FX miniseries adaptation, starring Gemma Arterton ("Byzantium") and featuring the second to last performance of the late Diana Rigg, who played the Queen of Thorns on "Game of Thrones."

Like the TV miniseries, the original film adaptation of "Black Narcissus," directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, is based on the eponymous 1939 novel by Rumer Godden. Previous Powell and Pressburger films had shot on location in places like Canterbury Cathedral and the Isle of Mull, but with "Black Narcissus," they pulled off an amazing sleight of hand.

The movie is beautifully lensed and has a sense of place like no other. The cliff alone sells its transportive allure. Yet the bulk of it was shot at Pinewood Studios in England, with matte paintings giving the illusion of real mountains in the Himalayas. In Martin Scorsese's DVD commentary for the Criterion Collection release of "Black Narcissus," he likened its aesthetic to a live-action Disney movie. It's "a cross between Disney and a horror film," he said.

Michael Giaimo, the art director of Disney's "Frozen," later drew inspiration from Powell and Pressburger's classic when designing the queendom of Arendelle (with its widescreen Cinemascope look also referencing Norwegian fjords). "Black Narcissus" won Jack Cardiff and Alfred Junge the Oscars for Best Cinematography and Best Art Direction, respectively, and it endures as a beacon of old-school movie magic.

Much has been written of the film's bristling sensuality. It's there right from the beginning as Mr. Dean, the resident, "Beguiled"-like man in their midst, makes eyes at the nuns and serves up innuendos. You can see how Scorsese might be drawn to "Black Narcissus" for that element, given his concern with the "battle of the spirit and the flesh" in films like "The Last Temptation of Christ" and "The Age of Innocence."

An imperialism of the arts

As an American expat, I find "Black Narcissus" especially interesting for its cross-cultural elements. There is one scene where we see the ambassadors of two different cultures, a nun and a man in princely Indian grab, standing across from each other with a literal cross or crucifix between them.

Before the nuns arrive at Mopu, Mr. Dean sets the stage in voiceover, matter-of-factly stating: "The men are men, no better, no worse, than anywhere else. The women are women. The children, children." Yet he speaks more condescendingly of them later, saying, "They're primitive people, and like children. Unreasonable children." Sister Ruth says "they all look alike" to her, while one of the real children, Joseph Anthony (Eddie Whaley Jr.), acts as a precocious interpreter for the nuns and teaches the other kids English vocabulary.

This is a 75-year-old British film that is still somewhat enmeshed in an imperialism of the arts, but it was surprisingly forward-thinking in some ways, not the least of which is Mr. Dean's prediction that the nuns and their school, hospital, and mission at Mopu won't last "'til the rains break." This will come back into play later in the film, which arrived months before the historic Partition that brought about the end of the British Empire in India and the beginning of modern Pakistan.

"Black Narcissus" remains a powder keg of eroticism and exoticism, but if there's one aspect of the film that has not aged well, it's the brownface depictions of two characters. Indian actor Sabu co-stars as the Young General, who, in some ways, is more affable and Christlike than any nun, never more so than when he refuses to whip the thieving beggar-maid, Kanchi, in a moment that recalls the biblical story where Jesus defended an adulterous woman by saying, "Let he who is without sin cast the first stone."

Kanchi herself is played by Jean Simmons, a white British starlet in brownface, while the Old General, who believes "Europeans eat sausage," receives a similar makeup job and is played by Esmond Knight, a half-blind World War II veteran and English actor.

Sister Superior and suffering servant

In "Black Narcissus," characters' faces are often filmed in intimate close-ups, which accentuate their psychological state. The lighting brings out every line in the face of the older Mother Dorothea (Nancy Roberts), rendering it a work of art as she bestows wisdom on Sister Clodagh, the new Sister Superior, with the words, "The Superior is the servant of all."

The spinning shadows of ceiling fans cross over both nuns in their flowing white habits as they look down at a banquet table that resembles a jewel-studded cross. Later, we'll see the shadow of a cross fall over Sister Clodagh's face and heart as she kneels in a chapel and flashes back to her old lipstick life at a shimmering lake, where romance was still a possibility. The way her painted flashback face dissolves back into her hooded, makeup-free physiognomy as a nun tells us all we need to know about her ascetic frame of mind and the emotional and spiritual journey that has led her here.

As Scorsese observes in his commentary, Sister Clodagh has another flashback later where she runs out the door, ready to embrace life and love, but it fades to black and she "goes off to nothing." All that awaits her there is the life of the suffering servant, a motif that runs from the Old Testament prophet of Isaiah to the New Testament figure of Christ.

It would be easy for a film like "Black Narcissus" to lapse into caricature and depict Kerr's character as repressed, but she comes off more as someone who is just self-disciplined, maybe a little prim. "Without discipline, we should all behave like children," she tells Mr. Dean, in response to his comments on the locals.

When Mopu and its endless field of depth, which extends to one's own past, begin to mess with the head of Sister Philippa (Flora Robson) and interfere with her potato planting, Sister Clodagh advises her to work, and work hard, until she's "too tired to think of anything else."

Dormant torment and the pull of the irrational

Sister Philippa already is too wrapped up in her work and has a pair of callused hands to prove it. And for Sister Ruth, torment is only dormant for so long before it erupts in full-on madness. Scorsese's commentary also reveals how "Black Narcissus" influenced the shifts between fantasy and reality in his film "The King of Comedy." And on a second viewing, Sister Ruth and her inner life and fantasy love life (exhibited through her behavior), stand out even more.

It begins when she dashes into Sister Clodagh's office, her white habit splotched with red, and speaks with excitement about how the nuns' hospital received its first bad case, a woman covered in blood. Sister Ruth stopped the bleeding, and you can tell she derives perverse pleasure from it because it was a thrilling life experience for her.

If anyone's repressed, it's her. Mr. Dean sees her out, and this is where she latches onto him as a romantic prospect. The title of "Black Narcissus" refers to a perfume, the scent of life, as it were. Mopu is suffused with that scent, and like some settings in folk horror, it represents the pull of the irrational.

Framing the movie in philosophical rather than religious terms, you could even perhaps say that Sister Clodagh and Sister Ruth are avatars of what Nietsche called the Apollonian and Dionysian forces, respectively. Forget Aristotle's "rational man;" Sister Clodagh is Powell and Pressburger's rational woman. She's leery of Sister Ruth from the start, and aghast at how unconcerned she seems to be with the actual welfare of the bleeding woman she attended.

I'm going to embed two last images here, in one last section with spoilers for the ending of "Black Narcissus." If perchance you're reading this without having seen the movie yet, I'd encourage you to go watch it before looking or reading any further, as seeing the second image beforehand might lessen the impact of it when it comes as a stunning visual reveal in Powell and Pressburger's film.

Love and darkness

In "Black Narcissus," the wind whips through the open-air convent, fluttering hearts and robes. There is music (Mopu is a place where drums beat all night on deathwatch), but at times, it's as if the wind provides the film's true soundtrack. Summarizing the duality of all humanity in the material world, Sister Philippa realizes, "There are only two ways of living in this place. [...] Either ignore it, or give yourself up to it."

Sister Ruth gives herself up to it, surrendering wholesale to the wind and the wings of Dionysian desire. Gripped with hysteria, the transformation she undergoes in "Black Narcissus" is riveting to behold. She almost looks like a different woman by the end:

"Black Narcissus" builds to a gothic, feverish intensity, leading us back to the bell with Sister Clodagh and Sister Ruth for a final confrontation that ends in tragedy. When Sister Ruth throws open the doors to carry out her attempted murder, her eyes blaze jealously, but there are dark circles under them and she looks pale and sweaty, almost vampiric. In the end, she loses her life to forces beyond her ken, and Mr. Dean is proven right. Ostracized by the community they serve after a sick baby dies on their watch, Sister Clodagh and the nuns vacate Mopu right as monsoon season begins. They take the British Empire with them.

Like Mopu, "Black Narcissus" is both a palace and a prison for its characters, one that holds a mystical quality. If there's any recent film it halfway resembles, it might be Jane Campion's "The Power of the Dog," if only for the psychological warfare between its antagonist and protagonist. And if there's any more beautifully lensed film from the mid-1940s, I haven't seen it. This is a movie that taps deep into the human psyche to explore that age-old walking of the line between love and darkness.

If the first miracle Christ performed was turning water into wine, what's so wrong with Mr. Dean being drunk on Christmas? And at what point does that mentality, applied toward other things, open a weak-willed human up to excess and self-destruction? The only possible answer, which "Black Narcissus" itself recognizes, is, "Yes, we're all human, aren't we?"