The Daily Stream: Garden State Captures The Heartache Of Growing Up

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The Movie: "Garden State"

Where You Can Stream It: Prime Video

The Pitch: Zach Braff, the guy everyone got to know as J.D. in "Scrubs," wrote and directed a movie in 2004 about a young man named Andrew (Braff), a struggling wannabe actor who gets a phone call one morning that his mother has died. He returns from LA for the funeral and discovers that "home" isn't what he remembers, and he isn't sure he can ever actually truly feel at home again. He runs into some old high school buddies and finds a new love in manic pixie dream girl Sam (Natalie Portman), but he still has to reconcile with his grief for his mother, his childhood, and his own sense of self.

While "Garden State" has been critiqued for being overly earnest, too sentimental, and even "whiny," there is something profound at the core of Andrew and Sam's experiences. Most coming-of-age movies focus on adolescence, when we first diverge ourselves from our parents and start becoming adults for the first time — but "Garden State" looks hard at the second coming-of-age that many people go through, when they confront the horrifying fact that they are the adults now.

Why It's Essential Viewing

In "Garden State," Andrew seems to have been running from his hometown. When he returns for the funeral, everyone points out that he got out of New Jersey as soon as he graduated and never looked back. Some clearly feel abandoned, while others joke about his minimal Hollywood success. What they don't know is that he's working in a weird, racist Vietnamese restaurant where the servers all dress in stereotypical clothing and wear eyeliner, and that he's deeply, horribly depressed.

His father (Ian Holm) is a psychiatrist who has served as Andrew's shrink since he was a child, and he keeps his son heavily medicated to the point that he feels almost nothing. It turns out that Andrew's fears of home result from childhood trauma: when he was nine and having an argument with his mother, he pushed her and in a freak accident she fell and was paralyzed. He clearly blames himself and that's why he ran as far away as he could, but once she's dead he realizes there was so much left unsaid.

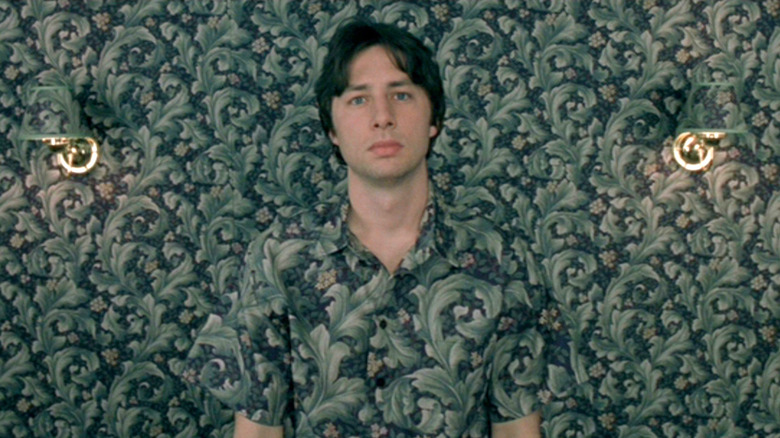

Most of the movie is Andrew having small, weird adventures around his New Jersey hometown. There's a funeral for Sam's hamster, an elaborate hunt for some Desert Storm trading cards that ends at a houseboat in the bottom of a rock quarry, and a whole lot of quirky shenanigans. The cinematography by Lawrence Shur ("Joker") is top-notch, giving the movie a slightly surreal, magical realism quality that helps make it more of a whimsical journey than just an angsty man's random wanderings. Braff's direction is good, steered by his connection to the work, and his performance is his standard schtick: he's a sad boy in a sad world who doesn't know how to handle it.

Thankfully, Portman is perfect as Sam, bringing pathos to her manic pixie character and injecting her with a bit of depth absent in Braff's script. Peter Sarsgaard is equally great as Andrew's old high school buddy, Mark, who digs graves for a living and has the kind of life Andrew was terrified he would have been stuck in if he had never left New Jersey. There are a few weird moments that don't quite hold up, like Sam's "adopted" brother Titembay or the aforementioned Vietnamese restaurant, though these can be attributed to Braff's privileged, limited view of the world.

While "Garden State" does a lot of emotional digging, it's also very funny in a dry, sideways kind of way. Many of the film's biggest gags come from absurd situations, like Andrew waking up the morning after a house party to see a knight in full armor pouring himself a bowl of cereal. Life is weird, and "Garden State" embraces that weird for laughs. This is a movie where Method Man plays a hotel bellhop who hosts secret peep shows to watch the rich and famous have sex in their rooms, then demands that everyone who "saw some t***ys" raise their hand. Denis O' Hare is a "guardian of the abyss" who lives in a houseboat with his wife and son at the bottom of a quarry and serves anyone who comes by tea. Just roll with it.

Homesick for a place that doesn't exist

"Garden State" is at its best when it's examining Andrew's relationship with his parents and his own childhood. He has to learn to let go of his resentment: for ccidentally paralyzing his mother, for his mother not being able to fully be there for him as a result, and for his father just numbing him to everything. Once he finally starts feeling again, he realizes the profound grief deep inside of him and is finally able to let it out in a primal scream from the top of the rock quarry. He feels untethered, unmoored from everything that helped him shape his identity, and it's deeply relatable — for me at least.

I had a (relatively) happy childhood and have a much better relationship with my parents, but there came a time in my late 20s where I realized that the comforts of childhood had all completely fallen away. My childhood home had been sold, my grandparents' home from my childhood was no longer theirs, and for the first time in my life, I had to try to make my own home without those built-in sentiments attached. I felt lost, separated from my family by both distance and time, and updates from them or time with them often only made the pain more acute because it reinforced that things would never be the same. I began noticing the streaks of gray in my parents' hair and realized that before I know it, I'll be the one taking care of them. Andrew says it best in the film when he's explaining his heartache to Sam:

"You'll see one day when you move out it just sort of happens one day and it's gone. You feel like you can never get it back. It's like you feel homesick for a place that doesn't even exist. Maybe it's like this rite of passage, you know. You won't ever have this feeling again until you create a new idea of home for yourself, you know, for your kids, for the family you start, it's like a cycle or something. I don't know, but I miss the idea of it, you know. Maybe that's all family really is. A group of people that miss the same imaginary place."

My grandfather died this past autumn, and he helped raise me. I hadn't really thought about "Garden State" much outside of some of the humor or the weirdly dated indie soundtrack, but something about his passing made what Andrew said crop up in my mind. As long as my loved ones were alive, I had the idea of home through them. Sure, I couldn't play cribbage and have sandwiches and milk in my grandparents' old kitchen the way I did as a kid, but I could still hug them tight and share the memories of that place together. His death was the end of that era of my life, and without him around to miss the "same imaginary place," the world will never quite feel the same.

There's no fixing that. I have made a new home for myself with my husband and dog and I am close to my family, but it will never be exactly the same, and that's okay. "Garden State" tells us that the greatest disservice we can do to ourselves is avoiding the pain. By not feeling it or running away from it, we never process our feelings and we can never even begin to heal. The movie doesn't give any answers on how to fix the holes in our hearts beyond "find love" and "have friends," but it does provide a great portrayal of the awkward period in your life where you've "grown up" but you have no idea what's next.

Sometimes, just knowing that something you're feeling is a part of life can be reassuring. Experiencing the shakiness of early "real" adulthood through someone else's eyes can make our own shakiness feel a little more normal and a lot less scary. Sometimes, it's just nice to know you're not alone.