The Daily Stream: The Staircase Casts A Reasonable Doubt On The American Justice System

(Welcome to The Daily Stream, an ongoing series in which the /Film team shares what they've been watching, why it's worth checking out, and where you can stream it.)

Series: "The Staircase"

Where You Can Stream It: Netflix

The Pitch: Kathleen Hunt Atwater Peterson, born February 21, 1953, was an accomplished engineer — an early woman-graduate of Duke University's school of engineering — and a dedicated volunteer beloved by her community in Durham, North Carolina. Her sister Candace Zamperini sang her praises as a woman who could do it all. "She was absolutely an amazing person," her sister said, "I'm still in awe of her. She was an amazing executive and scholar ... and she could cook and sew." On December 9, 2001, Kathleen Peterson was found dead at the bottom of a staircase in her home that she shared with her husband, author Michael Peterson, who discovered her body. The scene was grotesque; Kathleen was covered in blood, an impossible sight to reconcile with her husband's tearful claim that she fell down the stairs after having a bit too much wine. One look at the video or photos of her and the first thought is likely, There's no way that came from falling down some stairs. Someone did something to that woman.

Tragedy quickly turned to scrutiny as all eyes immediately landed on Michael, and shortly after his indictment, French filmmaker Jean-Xavier de Lestrade began to chronicle the saga throughout Peterson's murder trial. The result is "The Staircase," a comprehensive miniseries that gives what feels like an unprecedented look at the American judicial system in action, for better or for worse. With an adapted series starring Colin Firth on the way to HBO Max this May, now is a great time to watch the story that inspired it.

Why it's essential viewing

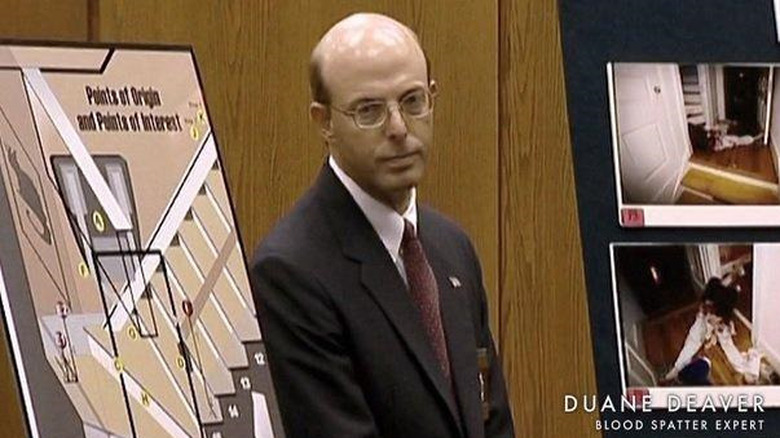

"The Staircase" is an account of one man's trial for murder, of course, but the documentary exposes the criminal justice machine, its machinations, and flaws. From search warrants to evidence admission to expert testimony to charged phrasing on medical documents, there exist a minefield of gray areas that a determined prosecution can manipulate to their advantage. One expert testimony from North Carolina's State Bureau of Investigation (SBI) blood spatter analyst Duane Deaver convinced the jury that the only way a spot of blood could have gotten on the inside of Michael Peterson's shorts was by his beating her to death, which worked out fine until he was fired in 2011 after an SBI audit revealed that Deaver falsified evidence in a total of 34 separate criminal cases — including the Peterson case. Those who believe that Michael beat his wife to death might shrug at the legal obstacles put before him, but the implication that it's all routine should be sobering for any American citizen. No matter which side of the fence you're on, it's horrifying to see examiners look at autopsy photos and essentially guess how the lacerations got there, often at the behest of someone with a conclusion to meet (rather than simply the truth) – and people's lives rest on that guesswork.

The burden of proof is on the state to secure a conviction. In other words, Michael doesn't need to prove his innocence as much as the state needs to prove that he did what they say he did beyond a reasonable doubt. Then-Durham County District Attorney Jim Hardin and assistant prosecutor Freda Black must present evidence at the trial to support their assertion, and convince the jury that there is no other reasonable explanation that can come from that evidence. The phrase "beyond a reasonable doubt" becomes paramount as the lack of a murder weapon, the strange nature of Kathleen's injuries, and a vague timeline make it legally difficult to conclusively point the finger at Michael. As each episode progresses, the defense team — led by David S. Rudolf — is almost reverent towards reasonable doubt, pointing out time and time again that the things they were bringing up (Michael's bisexual infidelity, for example) did not constitute proof, only prejudice. It all amounts to an unforgiving mess for all involved, and it's hard to maintain any sort of faith in the justice system once the final credits roll. "The Staircase" doesn't require an opinion on Michael's guilt, but that's unnecessary to be fascinated by what a criminal trial looks like in practice, and repulsed by how malleable the truth is in a courtroom.