The Coen Brothers Got Experimental To Create The Look Of O Brother, Where Art Thou?

We often hear filmmakers lamenting the declining use of celluloid to make movies. People like Quentin Tarantino are strong advocates for not just shooting on film but projecting movies on film as well. Whether you are fervently pro-film or pro-digital (or neutral on the topic), there is an undeniable difference in the feel of the image between the two formats, be it resolution, grain structure, and how they capture color and light. Each have their benefits and deficiencies. Personally, I am celluloid guy, not just because of the quality of the image, but I feel the format's inherent limitations require the filmmakers to take a little more care when composing shots. Obviously, there are plenty of tremendously beautiful digitally shot movies and horribly shot movies on film, but when the two are done right, the Pepsi challenge between them always results in me picking film, for both shooting and projecting.

While these filmmakers are so intent on holding onto the analog format, there is one aspect of the analog moviemaking process that rarely is ever brought up. I'm talking about color timing, the manipulation of color in a shot. Almost nobody out there is an advocate for old school color timing. The days of adjusting red, blue, and green lights through a printing process are long behind us. Post-production now is almost entirely a digital workflow at this point. We edit on computers, construct visual effects on computers, create titles on computers, sound mix on computers, and sometimes even make entire movies on computers. Obviously, this means color timing has become a digital process as well. This massive change in how we manipulate the color of an image started happening at the turn of the 21st century, and directing duo Joel & Ethan Coen, along with cinematographer extraordinaire Roger Deakins, were at the forefront with their period buddy comedy "O Brother, Where Art Thou?"

The digital revolution

Back in the 1990s, we had the advent of the digital intermediate, essentially the scanning of a film in order to digitally manipulate the images. At first, this was basically done for visual effects purposes. Movies like "Super Mario Bros." and "Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace" would scan visual effects plates for compositing purposes into the computer. However, they would not color time these movies digitally. They would still ship the films back out to the labs after the effects had been implemented.

The first movie to use a digital intermediate for timing was the Gary Ross' 1998 picture "Pleasantville." This is a film that mostly takes place inside the black and white world of a 1950s sitcom, where two people from the real world are transported inside of it. Throughout the film, certain people, places, and objects start turning to color as they become enlightened to the realities of sex, love, and other strong emotions and experiences. The traditional color timing process could not achieve this effect. You cannot isolate specific elements of a frame, as adjusting the RGB lights would effect the entire image. "Pleasantville" was shot entirely in color, and in post production, they opted to try this new digital intermediate technology to change everything into a monochromatic image, while working around the elements they wanted to remain in color. It was a true technological breakthrough. However, the entirety of "Pleasantville" was not color corrected this way. Some of the movie is entirely in color, and those sections still went through the traditional photochemical process.

The sepia-toned Soggy Bottom Boys

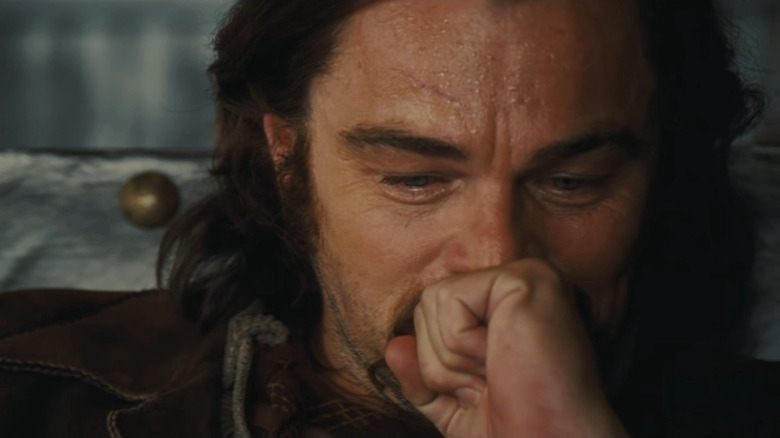

The honor of the first Hollywood movie to be entirely color timed through a digital intermediate belongs to "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" The Coen Brothers and Roger Deakins aimed to infuse the entire film with this yellow, almost sepia-toned look to evoke the Great Depression era the film is set in. The problem was two-fold. One, they didn't want the movie to just be sepia. That you could do photochemically, as there have plenty of films, like "The Wizard of Oz," manipulating color that way before. Instead, they wanted it sepia-adjacent, looking faded and old. The other was that they shot the film in Mississippi, a place which Joel Coen described as being "greener than Ireland" during a Q&A at the New York Film Festival.

At this point, the standard procedure was to just do it the traditional way. However, their tests were not turning out so great. At the aforementioned Q&A, Roger Deakins said, "We tried to do it with film, and it ended up being like six different chemical processes, and we never got anywhere close." That's when they got the idea to take a page out of the "Pleasantville" book and try out the digital intermediate. Deakins went on to say:

"It took days and days just to do a single shot when we were testing, but we all agreed that the film wouldn't be in post-production until about six to eight months, so we went ahead and took the chance with it ... Eventually, when we did the DI, it took over 11 weeks, so it still wasn't quick. It was all digitized — what we didn't want was a traditional sepia — the guys had told me they wanted the feel of an old, faded postcard and particularly to get rid of the greens. Digitally, you can select different colors, and basically there were a number of selections where you could change any color in the image."

The process was arduous, but they could not deny the results. There is barely a shroud of green in the entire film. Every blade of grass and every leaf look sun beaten and dead. The air looks like it is filled with dust, like you need to blow on the picture to clean it off. "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" could not have looked the way it does through any other process, and they ended up revolutionizing an entire industry in the process.

A stylistic choice leads to the new norm

The Coens and Roger Deakins turned to the digital intermediate for "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" to achieve a specific stylistic look they could not replicate anywhere else. This was a tool to them. After all, their next film together the following year, the tremendously underrated noir "The Man Who Wasn't There," did not use a digital intermediate in its color grading process (yes, black and white movies still need to be graded). However, the floodgates had opened, and using a DI to finish your film became standard practice. Now, finding someone who doesn't use a DI to grade their film is like finding a needle in a haystack. Actually, they don't even scan film anymore. Most films shoot digitally now, so the workflow over to digital color grading is fairly seamless.

Even Quentin Tarantino, the purest or the purists when it comes to analog, celluloid moviemaking came around to the digital intermediate. Outside of 2015's "The Hateful Eight," which was shot on 65mm and photochemically timed, all of Tarantino's films post-2000 have utilized a DI. Now, Tarantino puts limitations on how the DI can be used for color timing. For instance, his longtime cinematographer Robert Richardson said on the "Behind the Screen" podcast for The Hollywood Reporter that he does not allow windowing (isolating certain areas of the frame to time individually) in his timing:

"Quentin doesn't want windows, which 'windows' means ... if I don't like a wall and it's too bright, in digital, I can darken it and hide it. Quentin doesn't want that. He wants me on a set to darken that wall. Now, that takes more time, but it's Quentin's evolution as a director. It's his philosophy, and I acknowledge that philosophy."

The process has become so normalized that people don't even give it a second thought. If you want to shoot, you already start having people turn their heads. If you then decide to eschew the DI, people don't know what to do with themselves. So, if you want to have your film to have the right color palette and have the colors match shot-to-shot nowadays, you better be prepared for a digital intermediate workflow.

The last of the photochemical timers

Photochemical color timing may be dying, but it isn't buried in the ground yet. A couple of cinema's other prominent celluloid purists refuse to go down the digital path, and their names are Paul Thomas Anderson and Christopher Nolan. In an interview with the Director's Guild of America, Nolan said:

"In fact, I've never done a digital intermediate. Photochemically, you can time film with a good timer in three or four passes, which takes about 12 to 14 hours as opposed to seven or eight weeks in a DI suite. That's the way everyone was doing it 10 years ago, and I've just carried on making films in the way that works best and waiting until there's a good reason to change. But I haven't seen that reason yet."

Anderson and Nolan, though, can easily get the resources required to color time their films this way. Filmmakers working with much smaller budgets and without a studio backing them up are rarely as fortunate to even think they can color time the old school way. So, when a film comes along like Anna Biller's spectacular occult melodrama "The Love Witch," which aims to evoke the look of the color films by Alfred Hitchcock in the late 1950s and early 1960s, it is a feat of perseverance that they were able to not use a DI. In a piece for American Cinematographer Magazine, "The Love Witch" cinematographer M. David Mullen wrote:

"I think the main thing I re-discovered in post was how much contrast there is — how dense the blacks are — when you print a movie from the original negative at high printer lights. The look is much richer than what most digital projection can achieve today."

It's so funny how time completely reverses things. 22 years ago, the Coen Brothers were trying out a digital intermediate for "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" because they wanted to achieve a specific style of image for the film. In 2016, Anna Biller had to purposefully avoid the digital intermediate and use the traditional color timing process because of her own visual specificity. What that tells me is everything here is a tool, and filmmakers should be able to have access to all of these tools and use the ones the best suit whatever project they are making. Having an industry standard is limiting to the artistic process, and having different options available helps artists better achieve the vision in their heads, diversifies the looks of movies, and lets a lot more people keep their jobs in industries that have been ruthlessly chipped away at over the years. There is no right way to make a movie. There is just the right way to make your movie.