First Contact In The Star Trek Universe Explained

After the end of World War III, humanity will be left scattered and destitute. Colonel Phillip Green will lead a freelance army of eco-terrorists, controlled by drugs, to the slaughter of 37 million people. Nuclear bombs will be dropped, and much of the planet's surface will be seared by radiation. All the governments will have fallen, and torturous kangaroo courts will take the place of truth and justice. People will move into small enclaves throughout the world, modestly enjoying their limited resources and waiting for a proper economic system to restart.

In the middle of this terror, Earth will also experience its greatest day. On April 5, 2063, an engineer named Zefram Cochran will invent a craft that can, thanks to an energy field capable of warping the fabric of space, fly faster than the speed of light. On the maiden voyage of Cochran's ship, the Phoenix, a passing starship piloted by space aliens will change course to investigate. A cadre of Vulcans will land in Bozeman, Montana and introduce themselves to humans. Humans, realizing they are not alone in the galaxy, will begin a new age of togetherness and peace, understanding they are but new citizens in a much larger community. Over the years, warp technology will be used as the basis of a new age of exploration, allowing humanity to build enormous crafts capable of reaching other planets.

Over the course of the next century, Vulcans will prepare humanity for the next leg in the evolution of their civilization: Traversing the stars. We see the fruits of this, and examples of additional First Contact with alien species, in the new series "Star Trek: Strange New Worlds."

First Contact as an institution

These details are all laid out explicitly in Jonathan Frakes' 1996 film "Star Trek: First Contact." And, as with all lore introduced in "Star Trek," it became an oft-referred-to part of the franchise's lexicon. More importantly, however, first contact is — in the grand arc of "Star Trek" — the origin of Gene Roddenberry's benevolent vision of a peaceful future.

In the future of "Star Trek," humanity doesn't steadily and instinctually improve as a natural and expected outcropping of its history to date. "Star Trek" is not a story of how Earth nations decided to spontaneously get along, or how humans elected to rid themselves of prejudice merely out of the goodness of their hearts. "Star Trek" argues that humanity is capable of acting that way, yes, but that, when left to our own devices as a species, we lilt toward destruction and entropy. Gene Roddenberry looked out at the world as it was in the 1960s and saw a lot of problems. War, racism, sexual repression. These things were common. And they would not be undone by a starship, a transporter, or a stalwart military captain.

You'll notice that the optimistic future of "Star Trek" requires a clean slate. Much needs to be destroyed and removed before growth can begin. We needed to prove to ourselves, as a species, that we are capable of self-annihilation before we can build. The future can begin only after we allowed World War III to nearly wipe us out. Only at a moment of weakness, a moment of humility, a moment of shame, will our technical innovation be achieved ... for its own sake. In "First Contact," Cochran admits that he only wanted to achieve space flight as a means of making money. It wasn't until he was in space, looking back at a distant Earth after only flying for a few moments, that he realized the scope of his invention.

Paired with that innovation during a desperate time was First Contact. It's 2063, and humanity is essentially at its worst, and that was when another species reached out to shake our hands. To see that we were capable of a lot. First Contact was not just a plot point, but the beginning of Roddenberry's optimistic future. Seeing the greatness in ourselves through the eyes of other members in our astral community. First Contact is the "Star Trek" origin story.

First Contact throughout Trek

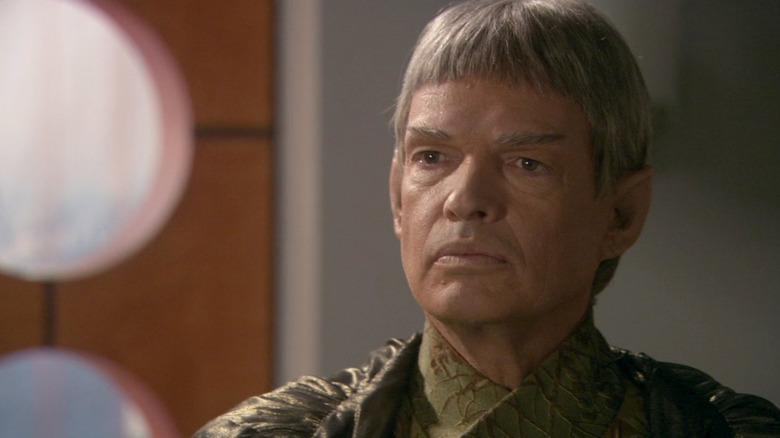

Because First Contact was so significant for humanity, it was depicted as a very careful process in future "Star Trek" episodes. Thanks to the franchise's well-known Prime Directive — the law that forbids Starfleet from interfering in the natural course of a society's development — the Federation is persnickety about how they introduce themselves to new worlds. Most importantly: The species in question has to be capable of faster-than-light travel. Often — as depicted in a 1991 "Star Trek: The Next Generation" episode called "First Contact" — Starfleet will send representatives in disguise down to a world that is on the cusp of developing warp flight to ensure that they are united. Are they eager to take to the stars, or are they only incidentally developing space flight while the rest of the planet preps for more war?

If the Federation finds the species in question is "ready" — there are no scientific measurements for said readiness, mind you; It appears to be based solely on diplomatic intuition — they will reveal themselves to the planet. Presumably, this will usher in a new era of peace and togetherness for that planet the same way it did for Earth. The Federation will them begin trade and, in some cases, many, many years of training to assure the species in question won't do anything reckless in the stars.

That last bit was the premise of "Star Trek: Enterprise." First Contact was in 2063, but the first Starfleet vessel didn't take off for another century. Those 100 years were needed for humanity to rebuild after the war, unify the governments, and gather resources to build the ships.

First Contact between two species that have both already achieved warp flight seems to be little more than a careful, polite, and formal introduction, and can be handled over a viewscreen. There is little concern with sociological evolution or culture taint in these cases.

Second Contact

Given the number of species seen on "Star Trek," First Contact seems to be common. It's mentioned frequently that Starfleet vessels have First Contact protocols, and, on "Star Trek: Lower Decks," senior officers talk about how much they love doing it. For them, it's a mere perk of the job.

One of the central gags of "Lower Decks," though, is that the central starship, the U.S.S. Cerritos, is often assigned the least desirable jobs in Starfleet. "Lower Decks" points out that "Star Trek" — however utopian it may be on paper — is still full of petty bureaucracy, heavy lifting, and mindless repetitive tasks. As such, "Lower Decks" has introduced the notion of Second Contact. While first introducing yourselves to a new species is thrilling, someone will have to follow up on the promise to begin a cultural exchange. The Cerritos is called in to negotiate trade, open lines of diplomacy, start tracking the new world's culture and the language, and share just enough tech to help them without giving them so much that their society would be tainted.

The captains get the fun of making a big speech about togetherness, but then someone else has to fly in and start quantity surveying.

Like most things on "Lower Decks," Second Contact is meant to point out that not everything is "Star Trek" is as easy as an inspirational speech. There's also an overwhelming amount of logistics that goes into it. Second Contact is proof that First Contact carries with it a lot of practical concerns.