Rain Man Ending Explained: Bet Two For Good

When it comes to portrayals of people with intellectual disabilities, there will always be a time before and a time after that controversial R-word speech in "Tropic Thunder." It was crude, but before that, it never really occurred to me that non-disabled actors might see such roles as a route to acclaim and accolades. Afterwards, I couldn't look some prestige performances by certain Hollywood A-listers in the same way again.

In the context of the scene, multi-award winning method actor Kirk Lazarus (Robert Downey Jr.) is taking issue with Oscar-baiting performances, implying that his rival Tugg Speedman (Ben Stiller) only portrayed a character with a disability to fast-track his career from brainless blockbusters to respectability. He calls out three real-life performances in particular; Dustin Hoffman in "Rain Man," Tom Hanks in "Forrest Gump," and Sean Penn in "I Am Sam." To this list, we could maybe add Robin Williams in "The Fisher King," Brad Pitt in "12 Monkeys," and Geoffrey Rush in "Shine."

While it is cynical to suggest that all actors playing someone with a disability — intellectual or otherwise — are just doing it to win trophies, it is noticeable that awards frequently find their way to performers in such roles. Back in 2012, the BBC worked out that 16% of all acting Oscars went to actors playing a character with a disability. The issue came into question again this year when "CODA" took Best Picture. If lesser-known actors with real disabilities can play people with corresponding disabilities so well, why have we needed big Hollywood stars to do the job in the past?

I saw "Rain Man" again recently after many years, and I was surprised by how low key Hoffman is. "Rain Man" is the oldest film mentioned above, and I think he probably became guilty by association with later showboating performances. The film was a hit for Barry Levinson and dominated the following year's Oscars, winning Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor for Dustin Hoffman, his second time winning. As Kirk Lazarus says, the Academy really were "about that s**t" on that occasion. But in taking a look back at "Rain Man," it seems Hoffman deserves the acclaim without qualification.

So what happens in Rain Man again?

Luxury car dealer Charlie Babbitt (Tom Cruise) is struggling financially when he receives news that his estranged father has passed away. He travels to Cincinnati for the will, fully expecting to inherit a fortune. Instead, he is only left a vintage automobile and some rose bushes, with his father's millions going to an unknown beneficiary.

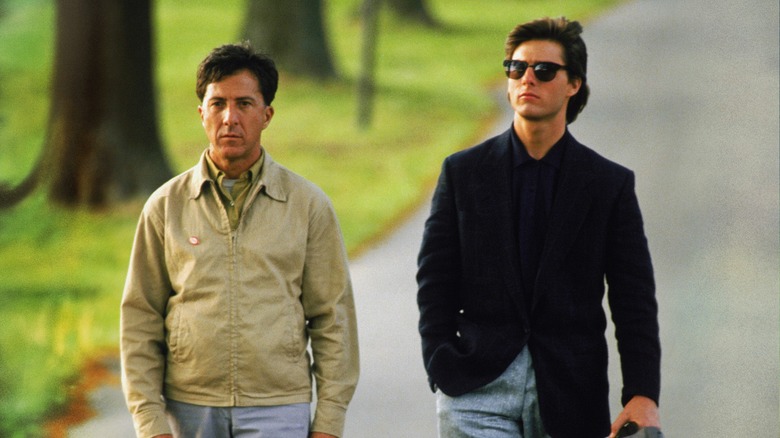

Charlie soon discovers the identity of the mystery heir: his older brother Raymond (Dustin Hoffman), who Charlie never knew existed. Raymond, who has autism and savant syndrome, lives a comfortable life in a mental institution where the staff are attuned to his routines. Aggrieved by losing out on the will, Charlie snatches his brother away with little regard for his needs, demanding half the money to return him. When his ransom is refused, Charlie decides to take Raymond back to Los Angeles and file for custody instead.

The journey gets complicated when Raymond refuses to board a plane or travel on the interstate. This leaves Charlie with no choice but to drive home on picturesque back roads in the beautiful old Buick and adapt to Raymond's routines along the way. Despite his initial frustration with Raymond's behavior, Charlie warms to his big brother and discovers money isn't the most important thing after all. But of course, he still has to use Raymond's savant abilities to count cards in a casino in order to earn back the money he lost in a canceled luxury car deal while on the road.

"Rain Man' is an effortlessly enjoyable road movie that isn't half as corny as it could have been. That's largely thanks to the detailed screenplay and two Hollywood greats playing to their strengths at very different points in their career. Cruise is so young and hungry in this movie, clearly relishing the chance to play off an actor of Hoffman's caliber and experience. While the older actor's well-researched performance is the most eye-catching, Cruise is in many ways the most impressive. His is the fully rounded character and he does a lot of the less glamorous character work, a dynamic that would be repeated a few years later in "The Fisher King," where Jeff Bridges grounded the whole film with the best performance of his career while Williams picked up the Oscar for the flashier part.

How accurate is Hoffman's performance?

Post-"Tropic Thunder," it is easy to regard these Oscar-winning portrayals of intellectual disabilities with skepticism, and Hoffman's performance at first seems like a compilation of autistic and savant behavior. He refuses to go anywhere in the rain and quotes Abbott and Costello for comfort. He memorizes half a phone book and can count fallen toothpicks at a glance. However, Hoffman put a lot of time getting the details just right, as Dr. Darold Treffert, an advisor on the film, explains (via Wisconsin Medical Society):

"Dustin Hoffman was carefully doing his homework for the part he very much wanted to do. He watched hours of tapes and movies of savants, both autistic and retarded. He studied scientific papers and manuscripts, talked to various professionals, visited psychiatric facilities and spent time with savants and their families to experience those relationships firsthand... In his remarkable portrayal of an autistic savant, Dustin Hoffman is careful to point out that while he studied these savants in-depth and got to know them well, he did not seek to imitate them."

However, some people take issue with how "Rain Man" portrays autism as an illness, as treatment and understanding of the condition has changed in over 30 years since the film was released (though it's clear in the movie that the medical world was still learning about autism at the time). Nils Skudra, who has Asperger's Syndrome, argues (via The Art of Autism):

"Hoffman states that he and Cruise felt that by showing enough love and empathy toward people on the autism spectrum, they could be released as if by a magic touch from their shell, a message which he hoped to convey in the film. While these intentions might have been well-meaning, they reflect a paternalistic and condescending belief that autism is a disease which can be cured, an attitude that would be widely considered offensive today."

In his article, Dr. Treffert pointed out that an earlier draft of the screenplay caused concern with its "happy" ending, where Raymond is able to change enough in a short period of time to live a rewarding life with his brother. Later drafts were altered to something more touching, complex, and realistic.

Here's the Rain Man ending explained

Over the course of the film, Charlies goes from an angry, self-centered individual to someone with genuine empathy for his brother's needs. One key aspect of this change of heart comes in a scene where Raymond reacts badly to a hot bath, scared that Charlie will get scalded. Charlie learns the Raymond had still lived at home while he was very young, and an accident involving hot water may have contributed to him going away.

The "Rain Man" of the title is how Charlie pronounced "Raymond" as a toddler, and Charlie had just thought of him as a comforting imaginary friend. This revelation evokes warm memories, and Charlie's attitude towards his big brother becomes far more understanding and affectionate after this point.

On the eve of Raymond's pre-court psychiatric evaluation, Charlie rejects a large cash offer from Raymond's doctor to just walk away. Charlie refuses, explaining that he is no longer angry about getting cut out of his dad's will, but is sad that he never knew about Raymond before.

The next day, after Raymond almost causes a fire at the house, it becomes clear at the evaluation that he is incapable of deciding for himself whether to stay with Charlie or return to the institute. Realizing that the psychiatrist's questioning is upsetting Raymond, Charlie calls an end to it. He does the right thing and sends his brother back where he can receive the proper treatment, understanding deep down that he can't give him the attention and care that Raymond needs.

Dr. Treffert addressed the ending's hopeful significance:

"In the original script there was a "happy ending." Raymond has changed so much that he does not return to the institution. He moves in with his brother, they go to ball games together and live happily ever after. While that makes a nice story, it also is an unrealistic one. The final script ending is as it should be. Raymond has changed slightly, some tentative closeness has emerged and one senses the beginnings of a transition, perhaps someday, to a life outside the hospital. It is a hopeful ending, but a realistic one, for all that one could expect in that six-day encounter is some new hope, not an accomplished cure."

Personally, I'm glad the ending was changed, leaving us with something more poignant and satisfying. What we have now is far more consistent with the story and the characters, especially Charlie, who has gone through significant changes over the course of the movie. At first, he was completely self-centred and didn't care about Raymond's needs at all and was really quite callous towards his brother. By the time he waves goodbye to Raymond at the end — closing with the callback line, "Bet two for good," a reference to their time spent betting in a casino — Charlie has opened up emotionally and become a far more empathetic person, although he still retains his tetchy arrogance throughout. We get the sense that the road trip has revealed a kinder side of Charlie to himself that he tentatively likes, and he will use the experience to become more understanding in his other relationships. Thanks to the strength of the screenplay and the performances, that positive arc doesn't feel forced or cheesy at all. Despite Kirk Lazarus' misgivings, "Rain Man" still works beautifully.