Dark City's Matrix Connection Goes Deeper Than Its Plot

Alex Proyas' 1998 film "Dark City" was, conceptually speaking, the first part of the "Matrix" trilogy. The second part was Wachowski Starship's own 1999 film "The Matrix," and the third was David Cronenberg's "eXistenZ," released the month after "The Matrix." All three films deal with insidious machines that can erase one's sense of identity and rob them of their agency. In all three films, the insidious machines are overseen by a malevolent force — they're run by inscrutable aliens in "City," by insidious A.I. in "Matrix," and by unscrupulous video game designers in "eXistenZ." The three films deal with the Cartesian notion of an existentialist manipulator attempting to distract their selected victim from the truth of the world. Each film is excellent.

"The Matrix," released by Warner Bros. in March, wasn't intended to be the runaway hit that it was; the intended blockbusters for 1999 were "Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace," "Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me," "Toy Story 2," and "The Mummy." "The Matrix" was one of several unexpected hits that year, which also included "The Sixth Sense," and "The Blair Witch Project." The Wachowskis' film took the world by surprise — their previous film, "Bound," was a modest critical success a few years previous — and the language of action cinema was changed for the better part of a decade. "Bullet time" began appearing in other movies, and dark cyber-thrillers became de rigueur.

Meanwhile, those of us who were paying attention in 1998 were eager — like the young, cineaste snots we were — to point out that many of the themes and visuals from "The Matrix" were already employed, arguably to greater effect, in "Dark City." We were the same people who, once "The Matrix" was rising in popularity, pointed out that Cronenberg revisited the same concepts, but did it better. Once we outgrew our contrarianism, we acknowledged that all three films are great and complement one another. Indeed, if one is generous, one may include "The Thirteenth Floor" in this series. Today, however, I am not feeling generous.

The connection between "Dark City" and "The Matrix," however, extends far beyond snotty coffee-house arguments in the late '90s. It turns out a lot of "Dark City's" VFX technicians created the look for "The Matrix" as well.

The color palate

The look of "Dark City" is unique. It is a blend of every shadowy cinematic cityscape in the history of the medium, presented as an artificial construct to the main characters the same way the cities themselves are artificial constructs for the audience. It is never daytime. When the clock strikes midnight, every single citizen in the city falls asleep, and hundreds of mysterious cloaked nonhuman figures appear from the shadows, give each of the sleeping humans a mysterious medicinal injection into their brains, and use their reality-warping mind powers to rearrange rooms and buildings. When the people awaken, they have an all-new identity and no memories of their previous life. To the main characters in "Dark City," all the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players.

"The Matrix" takes place in what is seemingly the real world, but is, in actuality, a complicated simulation being fed directly into human brains by a world-spanning A.I. that has, in the distant future, enslaved humanity in complex V.R. pods. When characters manage to escape from the Matrix — their nickname for the simulation — they wake up in a grim dystopia where the surface of the Earth has been claimed by a population of robots, and humans have been forced into hiding underground.

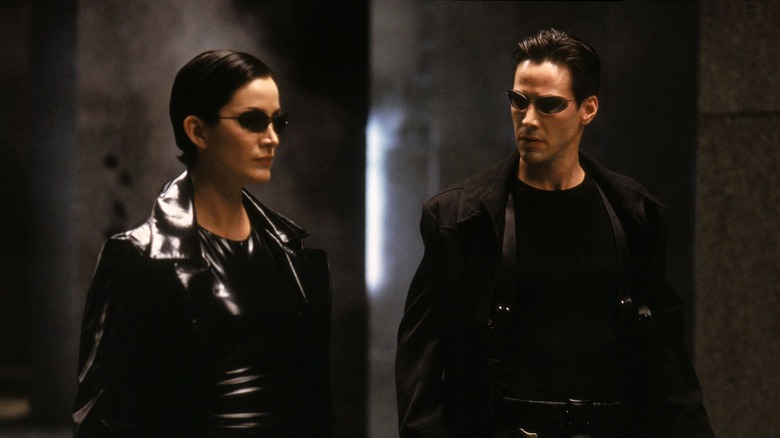

Two dystopias. One urban, one post-apocalyptic. Both are about savior figures (Rufus Sewell in "City," Keanu Reeves in "Matrix") who will eventually emerge from the illusions and do battle with their manipulators and destroy the simulation.

In an interview with the VFX Blog, VFX colorist Peter Doyle broke down a lot of the visual similarities with the films as well — because he worked on both. One might also recognize Doyle's work on Peter Jackson's film adaptations of "Lord of the Rings," and the various "Harry Potter" movies. Doyle works at Technicolor, and it is his job to artistically manipulate color temperature (working with a film's cinematographer) to give each film its own unique palette. In the interview, Doyle talked about working with "Matrix" VFX director John Gaeta and how they invented the look of the film:

" I'd known John from work back in Massachusetts, and I do remember sitting with [Lana] and [Lilly] after they had just been shown 'Dark City.' Because when they came through town with Barrie Osborne, the producer, the film hadn't quite been released yet, so they'd set-up to have a look. And then everyone just siting around laughing, realizing that they're just about to make 'Dark City' again but called 'The Matrix' instead.

Any panic?

There didn't seem to be any reported panic, but the Wachowskis did see "Dark City" while working on "The Matrix." Many of the technicians didn't see any kind of conflict, as there were only a few people working on that particular type of movie at the time, and it was inevitable that the two films share talent:

"Certainly that relationship was there, and some of the crew had also worked with them before. Sally Goldberg, who contributed a lot of animation and CG work, had also been working with me over at Massachusetts with John Gaeta and the team [on 'Eraser']. At the time, it was a very small industry. I think there were 20 Cineon licenses in the world."

[Cineon was an early computer-based digital film system developed by Kodak in the mid-1990s. According to a quick glance at Wikipedia, it was used for composting, visual effects, film restoration, and color management. It was used in 1993 to digitally restore "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs."]

Doyle liked what he did on "Dark City," even if the studio would — as is natural in a filmmaking environment — interfere.

"Personally, I'm very proud of the work. I actually really like the film. I think, as always, that there was some studio involvement, in terms of cutting, which is kind of inevitable. I personally feel that wasn't necessarily the best way to go."

But Doyle is wistful for what would eventually prove to be an ideal time in movie special effects:

"In terms of the work and the team we set up, we really had this almost halcyon concept of a group of people that are all equally skilled and working together. Rather than what is nowadays: Pretty much a very industrialized process. Which is necessary, I think. If you take on a major film nowadays, with 2,500 digital effects shots, it's not going to work to have a dozen of your buddies and yourself sit there and go, 'We'll get through this.' It just can't work."

It was also a time when the size of the VFX team could all get input straight from the director, and everyone was able to be on the same page:

"For me, too, 'Dark City' was an interestingly short period in the arc of visual effects production — or at least digital visual effects production — where one could feel that their contribution was effective and great and that one could have a true involvement in the process. The entire team would, in fact, interact with Alex [Proyas], as such. It wasn't people presenting the shots to me and then I would filter what is done and then present to Alex; it was much more egalitarian."

"Dark City" is available on Kanopy. "The Matrix" is available on HBO Max. "eXistenZ" is available on Pluto TV.