Everyone Loved Spartacus, Except For Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick's 1960 Roman epic "Spartacus," based on Howard Fast's biographical novel about an enslaved man who led an uprising against the Roman Empire during the third Servile War in the 70s BC, was one of Universal Pictures' biggest hits. Working with a budget of $12 million (about $115 million in 2022 dollars), the film grossed over $60 million (about $575 million in 2022 dollars). It was nominated for six Academy Awards and won four, including Best Supporting Actor for Peter Ustinov.

"Spartacus" also represents a dividing line in director Kubrick's filmography, between his more conventional "Hollywood" filmmaking and the more staid, experimental style he would come to be known for. Prior to "Spartacus," Kubrick had made a boxing film; "Fear and Desire" in 1953, which he hated; two noir films, "Killer's Kiss" in 1955 and "The Killing" in 1956; and a tragic film about a military tribunal, the excellent "Paths of Glory," in 1957. As his career was progressing, a large-scale studio production was the next logical step.

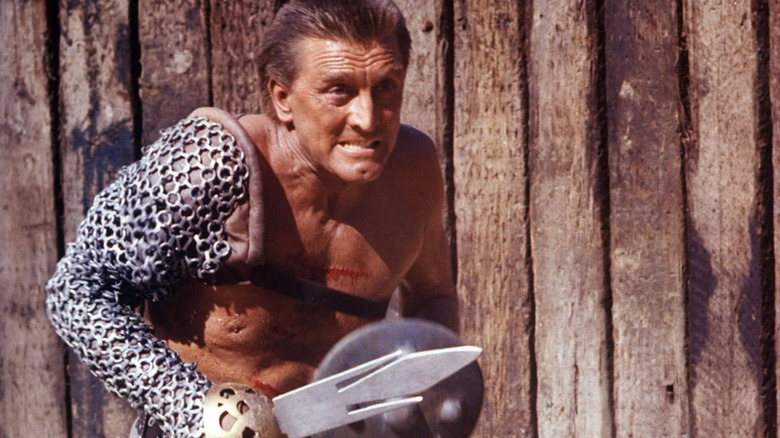

A film version of "Spartacus" was initially Kirk Douglas' idea. Douglas was smarting from losing the role of Ben-Hur in William Wyler's 1959 Christian epic to Charlton Heston, and, merely as an ego defense, put his own epic into production. Douglas was to serve as the lead actor and executive producer, and infamously blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo was to write. Trumbo spent the 1950s writing screenplays under various pseudonyms to avoid arrest. Douglas hired director Anthony Mann, who was best known at the time for directing Westerns like "Winchester '73," "The Naked Spur," and "The Tin Star."

Mann and Douglas butted heads throughout production, and Mann was fired after only a week (in his autobiography, Douglas would say that Mann seemed afraid at the massive size of the picture). Because Douglas worked with Kubrick on "Paths of Glory," the actor hired him to take over "Spartacus" after some of the film had already been shot and a lot of the look had been decided. Kubrick, being game, agreed.

The ultimate experience was miserable for Kubrick.

Who's in charge?

Stanley Kubrick had become accustomed to being in control of his smaller, earlier productions. He wasn't used to the financial stakes involved with a studio picture on the magnitude of "Spartacus." Unlike Anthony Mann, however, Kubrick wasn't intimidated. He was just frustrated that he didn't get to make all the final creative decisions.

Because "Spartacus" was Kirk Douglas' baby, the actor would reportedly take control of certain scenes, or direct actors off camera, leading to conflicts of information between him and Kubrick. No director would enjoy that. Additionally, "Spartacus'" cinematographer Russell Metty would butt heads with Kubrick. The director wanted carefully composed shots and multiple takes, whereas Metty wanted a more organic photography, allowing the natural action of the scene to dictate camera movements. Kubrick would end up shooting many scenes himself, locking Metty out. That "Spartacus" has any visual consistency at all is something of a miracle. Metty ended up winning an Academy Award for "Spartacus," and rightly so; he was the one who invented the look of the film, even if Kubrick shot additional scenes.

The headaches with making "Spartacus" didn't stop with shooting. A notorious scene in the middle of the film sees Spartacus' friend Antoninus (Tony Curtis) serving as a slave to the Roman lord Marcus Licinius Crassus (Laurence Olivier). In the scene, Crassus has a conversation with Antoninus about how some people have a taste for oysters, and some have a taste for snails, clearly making an allusion to sexuality. Crassus declares at the end of the scene that he enjoys both, perhaps making it the first bisexual coming-out scene of the Hollywood era. The scene was cut from "Spartacus" and wouldn't be restored until 1991. The sound had been lost, so modern renditions of the scene feature a rerecording of the dialogue with Curtis reprising his role, and Anthony Hopkins stepping in for Olivier, who had died in 1989.

The meaning of it all

Stanley Kubrick and Kirk Douglas couldn't agree on what "Spartacus" even meant.

Filmmaker Sidney Lumet stated in his famous instructional book, "Making Movies," that the director's sole job is to make sure everyone is making the same movie. That didn't seem to be the case with "Spartacus." Kubrick wanted the screenplay to reflect modern political corruption, especially as it was seen through the current horrors of the House Un-American Activities Committee — an ancient slave uprising as a metaphor for attacking a brazen ruling class who saw them as chattel for entertainment. Douglas took the side of Dalton Trumbo, as both of them wanted the protagonist to be a perfect hero, near-mythic, unable to falter or display weakness. Douglas briefly discusses Trumbo in the above interview with PBS show "American Masters."

Trumbo would later complain about what he suspected was Kubrick's tinkering on his screenplay in his 13-page "Report on Spartacus." Because he was blacklisted, Trumbo wasn't directly involved with the production and wasn't on set, having to stay in hiding. His central complaint was that Kubrick was making his protagonist "small." Kubrick sought to eject the mythic nature of the character and give a more human one.

Kubrick's complaint

In an interview with The Guardian in 1960, Stanley Kubrick gently laid out some diplomatic complaints about the big-budget process of shooting outdoors:

"The making of any film, whatever the historical setting or the size of the sets, has to be approached in much the same way. You have to figure out what is going on in each scene and what's the most interesting way to play it. With 'Spartacus,' whether a scene had hundreds of people in the background, or whether it was against a wall, I thought of everything first as if there was nothing back there. Once it was rehearsed, we worked out the background. ... When 'Spartacus' was being made, I discussed this point with Olivier and Ustinov and they both said that they felt that their powers were just drifting off into space when they were working out of doors. Their minds weren't sharp and their concentration seemed to evaporate. They preferred that kind of focusing-in that happens in a studio with the lights pointing at them and the sets around them. Whereas outside everything fades away, inside there is a kind of inner focusing of physical energy.

What went wrong

Years later, after Stanley Kubrick had drifted away from the Hollywood system and skewed hard into headier, more abstract cinema, he would make larger-scale and more impressive films like "2001: A Space Odyssey," perhaps the best science fiction movie ever made. By then, Kubrick was able to be a little more candid about how unhappy he was with "Spartacus" and what went wrong. In an interview printed in Scraps from the Loft, Kubrick laid it bare:

Then I did 'Spartacus,' which was the only film that I did not have control over, and which, I feel, was not enhanced by that fact. It all really just came down to the fact there are thousands of decisions that have to be made, and that if you don't make them yourself, and if you're not on the same wavelength as the people who are making them, it becomes a very painful experience, which it was. Obviously I directed the actors, composed the shots and cut the film, so that, within the weakness of the story, I tried to do the best I could.

Kubrick maintained that "Spartacus" was his worst film, and semi-disowned it for years.

Fans of cinema, however, may find a great deal of comfort in "Spartacus." On the one hand, they have a big-budget Hollywood epic to enjoy, even if the director didn't like it. And the experience forced Kubrick's hand into taking control of his films and making a long series of indelible classics according to his own whims. "Dr. Strangelove," "2001," "A Clockwork Orange," "Barry Lyndon" and "The Shining" were to come over the next 20 years, and the director would come to master the craft in a new way. In a parallel universe, perhaps Kubrick continued to make big-budget studio historical epics, but I am personally glad we exist in this one.