Disney's The Little Mermaid Had A Revolutionary Message For Its Time

In the wake of The Walt Disney Company coming under fire for sponsoring the politicians behind Florida's HB 1557, aka the "Don't Say Gay" bill, there's been a lot of talk about Howard Ashman, and rightly so. The late playwright and lyricist was fundamental to Disney's return to producing hit animated films in the 1990s (a period commonly referred to as the Disney Renaissance) after the box office failure of 1985's "The Black Cauldron" nearly drove the Mouse House's animation division into the ground. He was also a gay man who did much of his best-known work in the '80s, at a time when the AIDS epidemic was wreaking havoc on the LGBTQ+ population in the U.S., and President Ronald Reagan was going out of his way to avoid saying the word "AIDS," much less allocate much-needed federal funds for more research on and better treatment of HIV and AIDS.

Ashman advocated for the queer community through his song-writing for Disney's now-classic animated film adaptations of "Beauty and the Beast," "Aladdin" and, most notably, "The Little Mermaid." To quote The Smithsonian Magazine, he saw the studio's re-imagining of the (very different) 1837 Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale of the same name as "an opportunity to advance a social message through the medium of 'family entertainment.'" The result was a movie that made what was at the time a radical statement about gender roles and identity.

Part of your world

Now, before we continue, let's get this out of the way: Yes, "The Little Mermaid" is full of messy and problematic elements, be it the infamous "blackfish" in the "Under the Sea" musical number or how, on the surface (no pun intended), it's a story about a 16-year-old girl — that's right, in case you had forgotten, Ariel is 16 in the movie — altering herself physically and literally giving up her voice while pursuing a young man whom she ends up marrying. But as valid as most of the film's oft-raised critiques are, many of them draw from an incomplete reading of what "The Little Mermaid" has going on below the surface (... fine, that pun was on purpose).

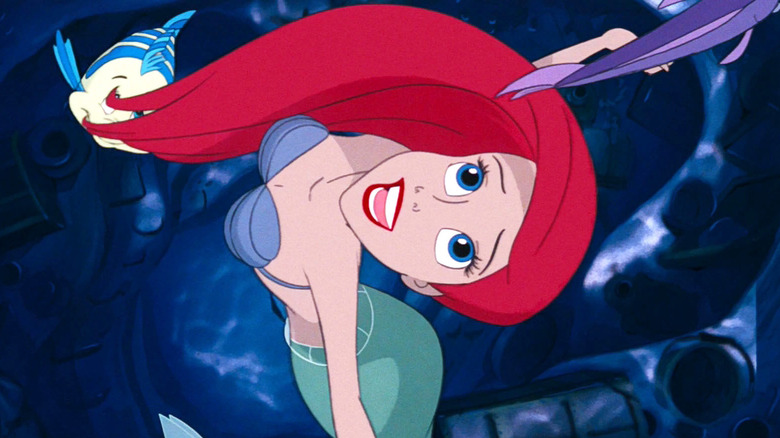

When we meet the titular mermaid Ariel, she's already in the middle of an identity crisis. Where her father, King Triton of Atlantica, expects her to join her sisters in literally singing his praises, Ariel has little interest in the customs of her patriarchal underwater society. Instead, she connects far more with people who live on the land and yearns to be part of their world, even collecting human artifacts in her grotto beneath the ocean. She is, for all intents and purposes, "in the closet," keeping the items that reflect who she truly is hidden in a cavern or "closet" away from Triton, who fears all humans and forbids Ariel from associating with them.

It's also important to note that Ariel wants to be a human before she knows her romantic interest in the film, Prince Eric, even exists. This is why the argument that "The Little Mermaid" encourages young women to "change" themselves for men has never quite sat right with me, even though I very much see where it comes from. All the same, it overlooks that Ariel's desire to be human is born out of her need to realize the identity she truly connects with and chooses for herself, rather than the one assigned to her by mer-society. While Ariel does fall in love with Eric after saving his life in a sea-storm, her quest to become human doesn't begin and end with him.

Poor unfortunate souls

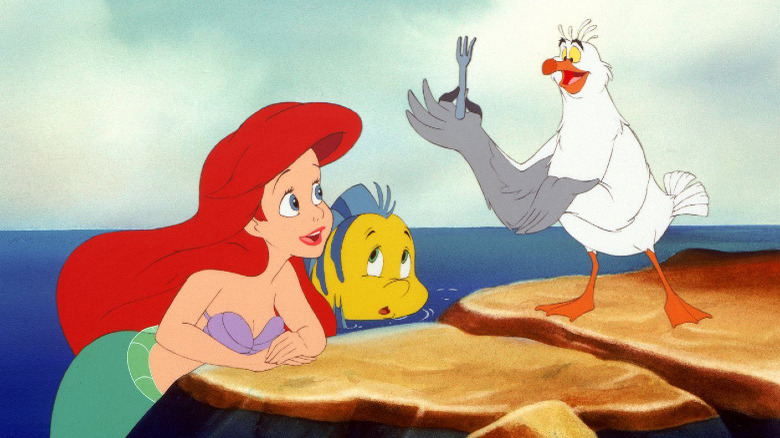

Upon discovering the truth about Ariel, Triton tries to force her to conform by destroying the human items in her grotto, including a statue of Eric recovered by her fish pal Flounder after Ariel rescued him. Reeling from her father's cruelty, Ariel sets out to become a human for real by striking a bargain with the sea witch Ursula, who was banished from Atlantica for reasons the movie doesn't specify. Cue Ursula's iconic musical number "Poor Unfortunate Souls," in which she teaches Ariel that (as Smithsonian Magazine puts it) "being a woman in a man's world is all about putting on a show" as a way of assuring her the deal Ursula has to offer — human legs in exchange for Ariel's voice and a chance to get Eric to fall in love with her — is a good one.

None of this subtext is by accident, either. Ursula was famously modeled after the actor, singer, and drag queen Divine, with drag itself defined by Merriam-Webster as a form of "entertainment in which performers caricature or challenge gender stereotypes." In light of this, Smithsonian Magazine argues the Ursula character "represents feminism, the fluidity of gender, and young Ariel's empowerment." Her mannerisms and personality were also heavily shaped by Ashman, as Ursula voice actor Pat Carroll recalled in a documentary included with "The Little Mermaid" for its DVD release:

"He was brilliant. I watched every body move of his [enacting 'Poor Unfortunate Souls'], I watched everything, I watched his face, I watched his hands, I ate him up!"

This is where things get complicated again. Ursula, like so many other classic animated Disney antagonists, is queer-coded, and "The Little Mermaid" presents her as being both the source of Ariel's liberation and a corrupting force on the young mermaid. By the same token, she also adheres to the frustrating trend of villains who raise valid criticisms of greater societal problems yet are saddled with negative traits as a way of undermining their critiques. Case in point: Ursula calls attention to some legitimate problems with traditional gender roles in human society ... but at the same time, she likes to make Monkey's Paw-style deals with mer-folk that benefit her and end with them becoming miserable polyps in her "garden."

The real Disney renaissance

"The Little Mermaid" ultimately wraps up in a conservative fashion story-wise, with Eric rescuing Ariel (she still rescued him first!) and saving the day by killing Ursula before marrying Ariel. But at the same time, this third act doesn't entirely abandon the film's more progressive subtext. Eric, for example, only truly falls in love with Ariel — without her voice — after getting to know her and does not hesitate to rush to her aid upon realizing she's been "passing" for a human this whole time. Triton likewise comes to see the error of his ways and uses his magic to change Ariel into a human upon Ursula's defeat, accepting her for who she really is.

After "The Little Mermaid," Ashman would go on to co-write the songs for the Disney animated films "Beauty and the Beast" and "Aladdin" before dying from complications due to HIV/AIDS in March 1991 (prior to either movie opening in theaters). If anything, though, those movies were even more radical than "The Little Mermaid" in their handling of gender, identity, and class, as well as their subversion of the tropes from Disney's older animated fairy tale re-tellings. This, in turn, spurred Disney's animation division to continue taking risks when it came to the types of stories it adapted into feature-films in the '90s, to results that ranged from admirably mixed to, at worst, downright cringe-worthy.

Still, for as varied as the results of the Disney Renaissance were, creatively speaking, they paved the way for even more ground-breaking and innovative animated storytelling from the Mouse House's artists in the decades that came after. And to think, so much of it goes back to Ashman and the ways he used a story about a young mermaid who wants to be "where the people are" to bring some pretty revolutionary messages to the moviegoing masses.