How Fantasia Went From A Box Office Bomb To A Cultural Touchstone

In the beginning, there was "The Sorcerer's Apprentice." Walt Disney wanted one last hurrah for Mickey Mouse, a chance to prove that he could compete with the likes of Donald and Goofy. For inspiration, he landed on a symphonic riff on a Goethe ballad by French composer Paul Dukas. But while the project was intended for the short format, it soon became prohibitively expensive. The only way for Disney and his staff to justify the cost would be to expand the short to film length. Disney considered his options.

Months before, Disney had a fortuitous meeting with the famous conductor Leopold Stokowski at a restaurant. Stokowski was overjoyed at the chance to conduct for "The Sorcerer's Apprentice," but had an even more ambitious project in mind. Why not attempt a full-length animated concert of classical music? At the time, Disney had deferred, but the troubles with "Sorcerer's Apprentice" made him reconsider. Together, what was initially known in-house as "The Concert Feature" mutated into "Fantasia."

"Fantasia" was the single most ambitious animated feature produced by Walt Disney to date. It featured career-best work by golden age animators like Bill Tylta, but also took inspiration from folks like the German-American abstract animator Oskar Fischinger (who was initially hired, but left early in production and was uncredited.) It was fearless in its musical choices, especially in its pick of Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring," whose premiere just a few decades earlier had caused riots in the theater. Even its presentation was maximalist. In the 12 theaters where the film opened, Disney sponsored the construction of the 96-speaker Fantasound system. A precursor to stereo sound, it ensured that "Fantasia" was to be a groundbreaking technological feat as much as it was an artistic one.

Night on Bald Mountain

Unfortunately, while "Fantasia" was a groundbreaking achievement, it was also doomed. The idea of a series of experimental short films set to classical music was simply too much for audiences who had fallen in love with "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs." Others found the idea of a cartoon for children engaging on equal terms with high art to be a ridiculous idea. To be fair, if you aren't willing to take the film on its own terms, "Fantasia" is a tough sit. Scene-by-scene it can be beautiful, silly, austere, boring, terrifying and deeply racist. Dorothy Thompson, a groundbreaking journalist who had been expelled from Nazi Germany a few years before, was truly horrified by the film and what it represented. "Naziism is the abuse of power, the perverted betrayal of the instincts...and so is 'Fantasia,'" she wrote in the pages of the New York Herald.

Today, Thompson's take on the film seems extreme (although the racism of "Fantasia" certainly deserves that level of critique.) But the last sentence of her review is the tell: "Bravo, Toscanini!" One of the most acclaimed conductors of that time, Toscanini believed in adapting scores as carefully and literally as possible. Stokowski was beloved by the public, but in practice he was Toscanini's polar opposite. His obituary in the New York Times features a telling quote from a man whose liberal interpretations of classical music were controversial among his fellow professionals. "That's a piece of paper with some marking on it. We have to infuse life into it."

While "Fantasia" was always a challenging prospect for its audience, I believe that it was Stokowski's feature role in the production that led to the strongest critical antagonism. Music critics like Olin Downes and Virgil Thompson lambasted Stokowski's arrangements in their reviews. Stravinsky, still living on the day "Fantasia" was released, ravaged its treatment of his "Rite of Spring." If "Fantasia" was meant to serve as an ambassador to the world of classical music, the world of classical music wasn't having it.

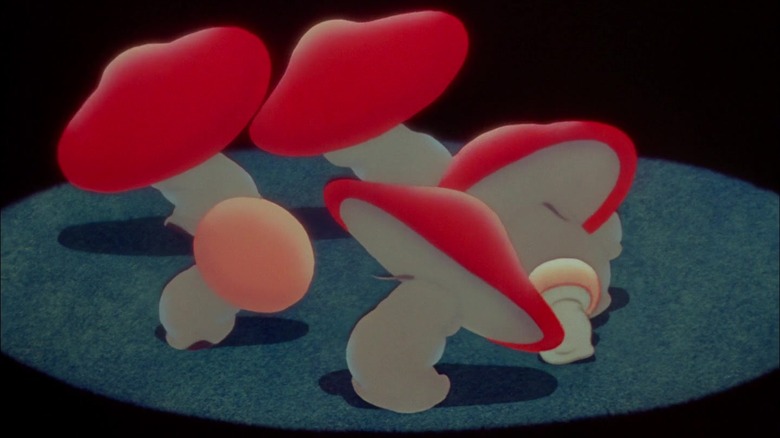

The Nutcracker Suite

In the end, despite its high ambitions and great expense, "Fantasia" was a financial disaster that nearly bankrupted the company. Its failure was felt immediately in future Disney projects, with the likes of "Dumbo" (as beloved as it is) showing an immediate course correction towards low-stakes family friendly entertainment. An ambitious plan to re-release "Fantasia" with a new set of animated shorts, set to pieces like Rimsky-Korsakov's "The Flight of the Bumble Bee," was killed in the cradle. (At least Thompson should have been relieved that we never saw the Disney version of Wagner's "Flight of the Valkyries.") Walt's brother Roy said of the reception to "Fantasia" that "the critics said he was trying to be something more than he was, and I think it affected him the rest of his life."

But the Walt Disney Company plays the long game. The film finally found success in its 1969 re-release, where it was rediscovered by a new audience of students looking to get high. The outrageous style of "Fantasia" sat much more comfortably in the year after the release of the film "Yellow Submarine." As the years went by, the film's legacy grew and grew, due to the work of critics like Roger Ebert. When the company brought it out from the Disney Vault for its 1991 VHS release, it insisted that the film would only be available to retailers for a period of fifty days. Advance orders hit 9.1 million copies. Once a pariah, "Fantasia" had graduated to cult classic and then to acknowledged masterpiece, as vital a part of the company's canon as "Sleeping Beauty" or "Pinnochio." Disney would even release a sequel years later in "Fantasia 2000," which had its moments but was much more hit and miss than even its predecessor.

The Rite of Spring

Today, the Walt Disney Company is an entertainment monopoly. It owns Marvel, "Star Wars" and Pixar. Between its films, theme parks, video games and television series, it makes a stupefying amount of money, more than any one person can imagine. It even influences copyright law in the United States. Yet despite the House of Mouse's power, its reach, and its full-hearted embrace of capital at the expense of the marginalized, it could never in its wildest dreams hope to produce a film as risky or bizarre as "Fantasia" today.

Walt Disney was a racist, a union buster and maybe even a fascist. But he loved animation as an art form, and when the chance came to blow open the doors of the medium and do something truly revolutionary, he took it. Somewhere out there are artists capable of the same ambition and craft that produced "Fantasia," toiling away in corners Disney would never touch. It's up to us to recognize them by the sound of their thunder, and find a place for them in glory outside the shadow of the Mouse.