The Web Of Real-Life Horror That Surrounds Rosemary's Baby

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

"Rosemary's Baby" is one of the most famous horror films ever made — and also one of the most infamous. The story itself is grim enough: Rosemary Woodhouse (Mia Farrow) is drugged by her husband, raped by the devil, falls pregnant, and eventually learns that she's been incubating the Antichrist. But the film also has a reputation for being "cursed" due to the web of horror surrounding it. From tragic accidents to shocking murders to creepy coincidences, "Rosemary's Baby" has a dark real-life aura.

Director Roman Polanski is perhaps the darkest element attached to the film. In 1977, Polanski was arrested and charged with drugging and raping a 13-year-old girl. He pled guilty to a lesser charge, but fled the country before sentencing and has since spent decades evading extradition to the United States to face charges.

Based on the novel of the same name by Ira Levin, "Rosemary's Baby" was released in 1968, a year that marked a radical shift in Hollywood movies. For the past few decades they'd been governed by the Hays Code, a set of moral guidelines so strict that even "suggestive dancing" and "superfluous use of liquor" were prohibited — so scenes of Satanic rituals were definitely out of the question. However, after the Hays Code was replaced with the MPAA's ratings system, there was an explosion of extremity in horror, especially when it came to previously taboo topics like religion and the occult.

The MPAA handed "Rosemary's Baby" an R rating, but it was given a "C" rating by the National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures — with the "C" standing for "condemned." This didn't do much harm at the box office, though; in fact, the notoriety may have even helped "Rosemary's Baby" become the huge hit that it was. And in the years since, the idea of the movie being cursed has only cemented it as a staple of the horror genre. Here are the stories that contributed to its reputation.

The tragic death of Rosemary's Baby composer Krzysztof Komeda

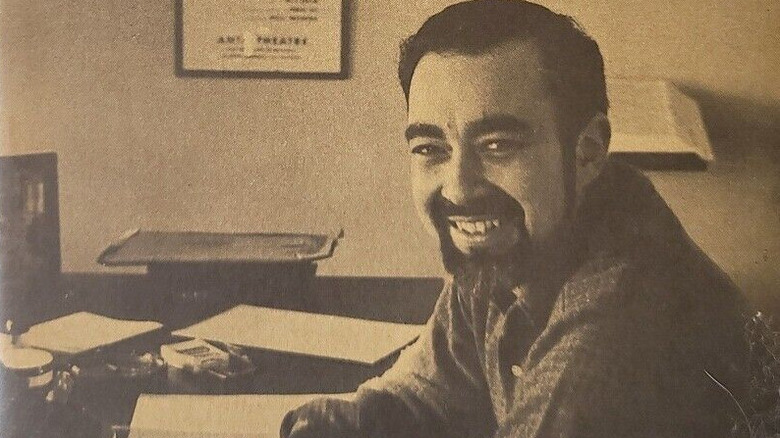

The score for "Rosemary's Baby," including the hauntingly beautiful signature theme "Lullaby," was composed by Polish jazz musician Krzysztof "Christopher" Komeda (pictured above, right). Less than a year after the film arrived in theaters, Komeda was dead at the age of 37.

The circumstances of his death weren't supernatural, but simply the tragic result of human error ... and superfluous use of liquor. In his memoir, Polanski recounted how he first learned that Komeda had been injured while drunkenly wandering Beverly Hills in December 1968 with their mutual friend, writer Marek Hłasko (pictured above, left). As Polanski tells it:

"[Komeda] showed up at Paramount looking awful, with two black eyes and a bump the size of an egg on his forehead. He'd fallen and hurt himself quite badly while roaming the Hollywood hills after a late night binge with Marek Hłasko. True to his he-man image, Hłasko had picked him up, using a fireman's lift. Then, being even drunker than Komeda, he'd stumbled and dropped him, injuring him some more."

In the weeks following the accident, Komeda developed chronic headaches. His doctor assured him that nothing was wrong, but in fact his brain was bleeding as a result of the head injury. Komeda's condition worsened, and a few weeks later he was rushed to hospital and fell into a coma. According to Polanski, "He came out of his coma once to scrawl a few disjointed words in Polish and once to beat time faintly on the counterpane when I played him some music on a tape recorder, but he never fully regained consciousness." Komeda died four months later.

There's another heartbreaking chapter to this story. Marek Hłasko had been wracked with guilt over the role he'd played in his friend's accident, and when Komeda was hospitalized, Hłasko reportedly declared: "If Krzysio dies, I will go too." In June 1969, two months after Komeda's passing, Hłasko died from consuming a lethal combination of alcohol and sleeping pills.

Rosemary's Baby is linked to the Manson Family murders

One of the most infamous crimes in American history shares a profound connection with "Rosemary's Baby." Polanski's own pregnant wife, actress Sharon Tate, was murdered by the Manson Family alongside four other people at Polanski and Tate's Los Angeles home. Orchestrated by notorious cult leader and serial killer Charles Manson, the murders shook the country to its very core. The killings took place in August 1969, when "Rosemary's Baby" was still showing in some theaters. And Polanski wasn't the only link between the fictional frights of the film and the real-life horror that struck Hollywood.

One of Charles Manson's motives for ordering the murders was to ignite his prophesied "Helter-Skelter" race war, in which Manson claimed that Black people would violently "rise up" against white people. In a flimsy attempt to frame the murders as part of this Black uprising, Manson's followers scrawled messages in blood at the scene — including "Healter [sic] Skelter." The name was taken from a track on the Beatles' White Album, released in November 1968, which Manson believed to contain coded messages about the impending race war. Manson Family member Paul Watkins later said that after the album was released, the cult listened to it around a campfire for days on end while Manson "interpreted" the lyrics for them.

Though Manson's ideas about the White Album were obviously nonsense, they do create another connection to "Rosemary's Baby." Many of the songs on the album were written during the Beatles' 1968 visit to India to study Transcendental Meditation with its creator, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Living and studying alongside them was none other than Mia Farrow, who had embarked on the retreat just two months after completing filming on "Rosemary's Baby." There's even a song on the album, "Sexy Sadie," that was inspired by John Lennon's anger over the Maharishi allegedly making inappropriate sexual advances towards Farrow.

The apartment building in Rosemary's Baby is supposedly haunted

The Manson Family murders aren't the only thread linking the Beatles to "Rosemary's Baby." The exterior shots of the gorgeous building that plays the role of the Bramford, Rosemary's new home in the film, used a real New York City landmark. The building, located on the corner of 72nd Street and Central Park West, is actually called the Dakota.

Built between 1880 and 1884, the Dakota has been home to a number of famous tenants over the years, including Judy Garland, Leonard Bernstein, and Lauren Bacall. One such celebrity resident was Beatles frontman John Lennon, who lived at the Dakota with his wife, Yoko Ono. The building made national headlines on December 8, 1980, when Mark David Chapman shot and killed Lennon on its very steps.

Even before Lennon's death, and before the filming of "Rosemary's Baby," the Dakota had a reputation for being haunted. In 1965, construction workers who were renovating the late Judy Holliday's apartment in preparation for its new tenants claimed to have seen the ghost of a man who had the face of a young boy. Residents have also reported sightings of a little girl in a yellow taffeta dress, bouncing a red ball through the halls. In the 1930s, an electrician called John Paynter said he had seen the figure of a short man with a long nose, a wig, and wire-framed glasses — matching the description of the Dakota's original owner, Edward Clark. Lennon himself claimed to have seen the ghost of a "crying lady" at the Dakota, and to have witnessed a UFO from the window of his apartment building.

After Lennon's death, his spirit was added to the Dakota's rumored roster of ghosts. Numerous people have reported sightings of Lennon's spirit over the years — including his widow. Yoko Ono recounted that one evening she saw her late husband at his piano, and that he turned and said to her: "Don't be afraid. I am still with you."

Mia Farrow's marriage ended on the set of Rosemary's Baby

In 1966, a little over a year before cameras started rolling on "Rosemary's Baby," Mia Farrow married Frank Sinatra. It was Sinatra's third marriage, and he was 29 years older than Farrow, so it would be a stretch to say that the marriage would have survived if it wasn't for "Rosemary's Baby." Still, the movie was ultimately the trigger point for their divorce — so much so that Sinatra had his attorney serve divorce papers to Farrow on set in front of the cast and crew.

Sinatra wasn't happy about his new wife having an acting career at all. "In terms of what Frank would say, I shouldn't have done any movies," Farrow told Vanity Fair in 2013. "He's on the record saying, 'I'm a pretty good provider. I can't see why a woman would want to do anything else.'"

If Farrow was going to continue acting, though, Sinatra at least wanted her to be acting alongside him. He offered her a supporting role in his upcoming movie "The Detective," with the intention that she would start filming scenes as soon as "Rosemary's Baby" wrapped. However, Polanski's demand for as many as fifty takes led to the production overrunning its original schedule. In his autobiography "The Kid Stays in the Picture," producer Robert Evans recounted how Sinatra called him up and told him bluntly that Farrow could either finish filming in time to start work on "The Detective," or he'd make her quit "Rosemary's Baby" altogether.

According to Evans, Farrow was prepared to quit to keep her husband happy. The producer convinced her to stay by showing her an hour of "Rosemary's Baby" that had been cut together, and telling her she was a "shoo-in" for an Academy Award. Farrow stuck with "Rosemary's Baby," and Sinatra had the divorce papers delivered to the set without warning.

Farrow didn't get an Oscar for her performance, but "Rosemary's Baby" significantly outgrossed "The Detective" at the box office.

Ira Levin had regrets about writing Rosemary's Baby

Ira Levin wrote a number of other well-known novels, including "The Stepford Wives" and "The Boys from Brazil," but "Rosemary's Baby" was by far his biggest hit. The box office success of the film had a domino effect in Hollywood, ushering in an era of devil-themed horror movies that dominated the 1970s — including "The Exorcist" and "The Omen." But this interest in the devil and the occult wasn't limited to the big screen.

The 1970s saw an explosion in fascination with all things magical and demonic, rising out of the counterculture of the 1960s. "Rosemary's Baby" can't be blamed for the founding of the Church of Satan, which was established by Anton LaVey the year before the book was published, but it may have accidentally functioned as an ad for Satanism. LaVey even started a myth that he was a "technical consultant" on "Rosemary's Baby," and that he had been the actor inside the devil costume on set. (The devil was actually played by Clay Tanner.)

Levin was aware of the role his novel had played in this movement, and later came to have "mixed feelings" about "Rosemary's Baby" because of it. The author came from a non-observant Jewish family, and didn't have any religious fears about empowering Satan. He thought belief in witches, the devil, and the occult was "nonsense" — and his biggest regret was contributing to the nonsense. "I really feel a certain degree of guilt about having fostered that kind of irrationality," Levin explained in a 1992 interview.

He echoed those feelings a decade later in an LA Times profile:

"I feel guilty that 'Rosemary's Baby' led to 'The Exorcist,' 'The Omen.' A whole generation has been exposed, has more belief in Satan. I don't believe in Satan. And I feel that the strong fundamentalism we have would not be as strong if there hadn't been so many of these books."

"Of course," Levin added, laughing, "I didn't send back any of the royalty checks."